Matt Karlsen

Home \ Opal School Blog \ Matt Karlsen

Staying Close

Through Opal School’s courses, I’ve been in conversations with teachers whose learning communities are impacted by the Covid 19 pandemic in the full range of…

DETAIL

The election, politics, and young children

In this election season, many of us are energized to deepen both our political advocacy and our pedagogy. I believe that we all need to…

DETAIL

Playful Inquiry and Politically Charged Topics

This post comes from our colleague Ben Mardell and is also posted on the Pedagogy of Play blog. Persistent and pernicious racism and inequality. Hurricanes…

DETAIL

An ecology of listening

“What’s the thing that most people miss above all? It’s just the chance to be gregarious, to be with other people. Human beings are socially…

DETAIL

The Max MacKay Rule: Decision-Making in the Time of COVID-19

These last days have come at us hard and fast. As we continue to respond and adapt, all of us at Opal School hope that…

DETAIL

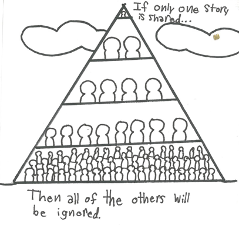

Making biases visible

Last week, families gathered to discuss how work currently happening at Opal School supports knowledge and dispositions central to social justice and global citizenship. Families heard…

DETAIL

Visitation Days 2020: New Models for Friendship

Last week, nearly 100 educators from around the world gathered at Opal School to uncover principles of Playful Inquiry and imagine greater opportunities for learning…

DETAIL

When your light goes out

Weekly, the Opal School elementary community starts its day with a community gathering. It’s a time when all four classes, along with many family members,…

DETAIL

Book Club: Inventology, Parts 3 & 4

I hope that you’ve been enjoying reading Inventology: How We Dream Up Things That Change the World – and that the Framework for Inspiring Inventiveness…

DETAIL

The Danger of The Guillotine

For the second year in a row, Opal School hosted a “Rising Educators Study Tour” for high school students who study approaches to early childhood…

DETAIL