Playful Inquiry and Politically Charged Topics

This post comes from our colleague Ben Mardell and is also posted on the Pedagogy of Play blog.

Persistent and pernicious racism and inequality. Hurricanes and wildfires of historic proportion. A pandemic that is increasing poverty and causing famines. Incredibly serious issues whose consequences young people will not only confront when they are finished with their schooling, but issues that also are impacting them now on a daily basis.

As an educator committed to bringing more playful learning into schools I wonder:

What is the role of schools in addressing these and other serious topics?

How can playful learning support inquiry into serious topics?

What does such playful learning look like in practice?

On Monday, October 5th, my PoP colleague Mara Krechevsky and I, along with our friends Susan MacKay and Matt Karlsen from Opal School, will examine these questions. As part of World Education Week, Opal is one of 100 schools from around the globe being showcased for its innovative practices. Our hour-long webinar, Engaging Ambiguity, Emotion, and Power: Invigorating democratic imagination through Playful Inquiry, begins at 5 pm GMT (1 pm in New York; 10:00 am in Portland).

You won’t be surprised that our answer to the first question about the role of schools in addressing serious issues is clear: a big one. We believe students, from an early age, have the right to engage, in developmentally appropriate ways, in issues of consequence.

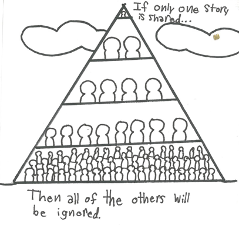

So how can playful learning support inquiry into serious topics, and what does this look like in practice? To answer these questions, Susan and Matt will share a story from Opal they call Inventing a Way Forward. The story involves a group of predominantly white, middle-class, 4th and 5th graders and how they and their teachers co-constructed an experience that connected the personal, local, and global – both past and present—to issues involving power and privilege. Specifically, Susan has written:

Throughout the school year the group played out the inevitable kinds of power struggles that are part of the life of any community. As we began studying the operation of the United States government, my co-teacher and I invited the children to work collaboratively to design a governing structure for their classroom community. By mid-April, the personal feelings that impacted our local classroom community had a strong resemblance to what we were seeing play out on the world stage. In particular, a group of children that had taken responsibility for operating the classroom library were increasingly livid with another group of children who refused to support the systems they put in place. When the tension began to run especially high, I met with this group and listened to their concerns. Interestingly, the group that was pushing so hard on the library were the children who were most used to being in charge, to voicing their strong opinions, and being listened to by others. Power and privilege is as local as it is global. But only on this local scale do we have a chance to go into it head on—to face it and tackle it in a real way.

At the same time the class read chapters from Ronald Takaki’s (2012) young people’s edition of A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America and we had another problem. We had asked the children to work in small groups to re-write the experiences of the protagonists in a chapter of their choice – both the powerful and the marginalized. We asked them to create a skit that would show what might have happened if things had gone differently and those in power had been willing to share it.

The children said, “Not a problem” and they enjoyed their work as they found ways to retell the history in their chapter. But when the class came together to share for the first time, they discovered that every one of the groups in their own way had the same problem. They could all walk right up to the confrontation – to the moment when the powerful would find a way to redistribute the power making things more equitable — and then they got stuck. Those with privilege and power had little motivation to give their power away. They all thought those who were oppressed could protest, threaten, or fight back, but they could find no reasonable way for both sides to get the relationship to move in a new, more fair direction. They couldn’t imagine it.

In the October 5th webinar, Susan and Matt will share the rest of the story and how the class found a way forward. We’ll also engage participants in the research process Opal School educators use to supports the creation of relationships and learning experiences that lead to meaningful democratic participation.

To sign up for the session use this link: https://www.eventbrite.dk/e/t4-world-education-week-tickets-116951472001?aff=Opal.

Click on the green registration button

Scroll down about 20 listings to 17:00pm to select our session…in the system it’s titled Playful inquiry: engaging children in democratic processes.

Racism. Wildfires. The pandemic. The issues I named at the start of this post can feel overwhelming and lead to despair. And I have found hope in the commitment, creativity and caring of educators at Opal School, and other schools, where young people are given the opportunity and support to engage in these issues and imagine futures where we create more just societies. Similarly, I hope that our session provides you with images of possibilities and promise.