It’s not about the spelling…

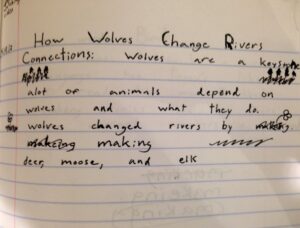

Recently in Opal 3, we were sitting together in a circle with our writing notebooks, a not uncommon scene for our third grade community. We had just watched a short video (How Wolves Change Rivers). I had asked the students to write to capture their thinking about the film and, perhaps through writing, to discover more thinking about the film. Suddenly, a student, who I will call Max in this post, leaned over to me and asked agitatedly, “How do you spell making?”

I frustrated him as I often frustrate my students by turning the question around, “How do you spell making?” He said, “I don’t know. That’s why I’m asking.”

The dialogue continued:

Hannah: “Hmmm. Do you want to leave a space and come back so it doesn’t interrupt your thinking?”

Max: “No. I can’t move on until I have the word!”

Hannah: “Have you tried it a few different ways?”

Max: “Yes, and none of them are RIGHT!”

I realized in the moment how unhelpful I was being. Max was upset and I felt as though I were making him more upset. I didn’t want him to be upset, but I also knew that I did not want to just tell him how to spell the word. I wasn’t sure why, in that moment, that it was such a big deal to either of us.

By now, other students had clued in to the drama that was unfolding. Seeing that their friend was upset, they joined in. “Just tell him!” they demanded. “Don’t you see that he is upset?”

Still knowing there was something important in this moment, but not knowing how to move the class or the student forward without just telling him how to spell the word, I stumbled on. “Do you remember learning a rule for this kind of word that might help you?”

In typical honesty, Max reported back that he didn’t actually pay attention in Word Study, so no, he did not remember any rule that might help. And then, he scrunched up his paper and started to cry.

It was the very end of the day. Someone handed Max a tissue and others offered kind words. Some students grabbed post-its and wrote how they thought the word should be spelled and handed it to the student. Others told me that he was upset and that I should help him. They said I should tell him how to spell the word.

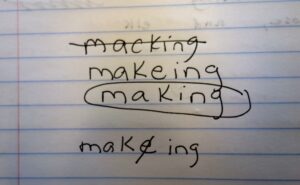

Then, the boy took a deep breath and said, “I know one way that it is not spelled.” So we wrote down one way that making is not spelled. We tried a few of the possibilities he had already tried.

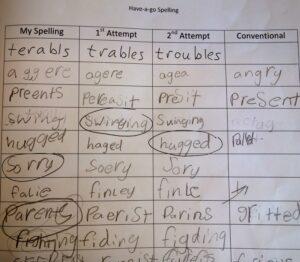

He was now using a strategy we call “have a go.” When students are not sure how to spell a word, I ask them to try writing the word in three different ways. Even if all three ways are not the conventional spelling, these efforts usually reveal important information and insights that students have about spelling. After trying a few ways, we talk about which one or which parts of the attempts make the most sense. According to this article, using, reflecting on, and talking about spelling as in this “have a go” method, will help students develop the letter-sound correlation needed for spelling. The article also states that the “best indicator of future success as a reader is actually a child’s ability to use invented spelling as he writes.”

After writing “making” a few different ways, Max was able to identify and write the conventional form of the word. However, this moment stayed with me for days afterwards. I couldn’t figure out exactly what it was that made me linger on what had happened. In the end, I didn’t just tell him and he did find a way to spell the word. I could have chalked it up to any number of things and left it at that. But, I knew it was not just about the spelling, despite finding support for my approach in the article.

But as I continued thinking about it, I started to realize what I wanted to put my finger on. I think it was about helping. I wondered about our perception of what helping is and is not. I wonder what is helpful – not the step in and save kind of helpful, but the kind of help that lasts, the kind of help that leads to greater independence, innovation, willingness to take risks, and more. The students thought I should help Max by telling him how to spell the word. It would have been quick and easy and painless. And, maybe that is where my resistance lay. I felt the tension between wanting to soothe my student and in wanting to support his stamina for when feeling challenged. As he got more upset, I wanted us to figure out what strategies he could try to regain his “thinking brain.” I had no doubt that when he was calm he would be able to figure out how to spell the word – I suspect he even knew all along, again re-iterating my belief that this moment wasn’t about the spelling. I wanted to help him by supporting him to persist in the struggle and to find not just a strategy to spell the word but what he needed to handle the struggle.

The situation invited me to reflect on why I don’t just give answers, to dig into why I say “How do you spell….” And “hmmm – what happens when you have a go?” When I dug in, I realized that I was trying to send so many messages to my students – messages of encouragement to take risks, to be open, to try different possibilities. Even more, I was trying to express confidence that they can try out challenges so matter how big or small. When I try to support students, I do not want my “help” to send a message that I think there is something they can’t do or that they can’t develop, discover or access the tools they need to figure something out.

With this new thinking in mind, I began looking and listening for opportunities to share my reflections on this small, short moment. I wanted to be transparent about my intentions behind my turning questions around. I also wanted them to know that I wasn’t sure what to do in that brief messy moment, and that I had continued thinking about it long after it happened.

And, as it often happens when we are looking for something, we find a way to find it, to make a connection, and seize an opportunity. Another morning, a few days later, we were sitting in a circle in the same place talking about interdependence and group dynamics. I had just turned a question back to the class (again!) and this conversation happened:

OC: And then sometimes other interveners come in and change things.

Hannah: How?

JK: I don’t know how! You asked the question.

SM: You always ask how!

TY: Some of the things she asks us she doesn’t even know!

Hannah: I don’t think of my role as telling you answers.

JK: But you have to say the answer!

Hannah: I ask you questions that I’m asking myself too. We try to construct understanding together. I think that’s going to be more powerful than me just telling you. That’s how I see my way of supporting – for us to chew on these things together. Max, can I use you for an example?

Max: Yeah.

H: I know that you sometimes can get really frustrated when you don’t know how to spell a word. Do you remember that time last week when you were upset about spelling a word? You might have felt like I was trying to frustrate you last week and I’m sorry if I did. I thought about that for a long time afterwards and realized what I was trying to say and do. I know in that moment my intentions didn’t come out very clearly. Do you want to know what they were?

Students: Yes.

Hannah: When I think about Max, who I dearly love and admire, I think about how I want him to have some strategies to for when he doesn’t know what to do. If I just tell him the answer does he get any strategies?

Max: I get the strategy for asking for the answer!

H: If I just give you the answer what message might I send?

TY: If you just tell him then he doesn’t have someone to tell him then he will get really frustrated because he won’t know what to do.

AD: You might be sending the message that you don’t want him to have strategies.

SR: On the same topic but….I was just thinking that if you give him the answer right away. If you have a locked door and that’s your challenge and the key is the answer, you have to use your strategies to get the key. If you give him the key every time, he won’t get the experience of using the strategies to find the key.

Hannah: And, if I give Max the answer each time I might also be giving him the message that I think he can’t do it. I never want to send that message.

This conversation gave me the opportunity to share my thinking and reflections about the event and to be transparent about my intentions and approaches. While I know I will continue to experience resistance to my questions at times, we now have this newly constructed and shared understanding of why just getting an answer isn’t as simple or as helpful as we might think or hope. I hope we have a sense of why we might not settle for someone just telling us something, whether it is about how to spell a word, solve a math problem, or something much more complex.

This experience leaves me still wondering about moments when my efforts to enable students may actually be disabling – when am I helping in a way that isn’t helpful in the long run? How can I respond differently when I notice my desire to “fix” situations or solve problems? How can I respond to students asking for help in a way that encourages them to persist when unsure without being completely undone? And, how often do I follow my own advice of having a go? Am I willing to be vulnerable and persist when I’m not sure too?

- What about you? Have you noticed some of these same tendencies or patterns? What have you found to be helpful, interesting, or challenging in situations like these?

- When is the last time you “had a go” when you were uncertain? What did you try and what happened? What did you notice?