The most important word is yet

In Alder, a community of 3-5 year olds, we were curious how children approached problems. We noticed how eager they were to run and get the strategy ring to support friends in conflict. Their heightened interest in this problem-solving tool led us to make strategy rings as gifts for the other classrooms.

The children offered this message to the school: This ring has a bunch of strategies on it. We use it to fix problems! If you try a strategy and it doesn’t work, try a different one. Keep going, don’t give up!

And Nelson added: I wish our whole community could solve problems together.

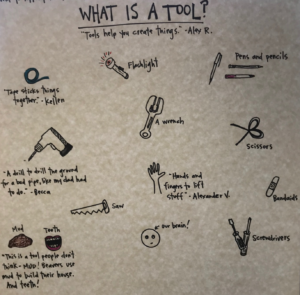

We were curious what tools they might begin inventing to fix the problems in the classroom, and began by asking what they already know about the word, tool.

They offered ideas such as screwdrivers, a flashlight, pens and pencils, bandaids and saws. We asked, What do these things have in common?

Alex: Tools help you create things.

Aurora: This is a tool people don’t think, mud. Beavers use mud to build their house. And teeth!

Kellen: Tape sticks things together.

Becca: A drill to drill the ground of a bad pipe, like my dad had to do.

Alexander: Our brains are a tool. We can use our brains to think about stuff!

One kind of problem that we observed in Alder is the gap between “I don’t know how” and “I do know how.”

There’s a gap between where you are and where you want to be. Many gaps, in fact, but imagine just one of them. That gap–is it fuel? Are you using it like a vacuum, to pull you along, to inspire you to find new methods, to dance with the fear? Or is it more like a moat, a forbidding space between you and the future?

This story highlights the gap and relies on the children’s relationships with materials, ideas, and each other to not only bridge the gap but also to fortify their sense of belonging in our community. As Diego stood at the edge of the gap, he viewed the space between him and the future as fuel to drive his courage and curiosity.

Just like Diego, we noticed the children were continually asking a teacher for help when they encountered a problem. And we noticed they rarely tried using the strategy of telling their feeling. We were curious why. How could we support their growing understanding of emotions? And how could we nudge them to take a risk and talk about their emotions with each other? Here’s a sneak peek into how we unpacked these questions.

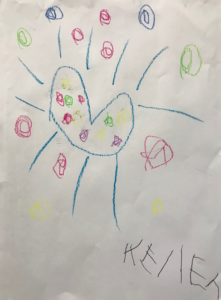

When Kellen drew a picture at the easel and said, “It’s love for everyone in Alder. It’s Alder Love,” we were curious to know more about his ideas and others’. So we asked the children one of the world’s most enduring and unanswerable questions, perhaps the greatest mystery of all: What is love?

Kellen’s drawing and this question launched our love research, which included the children writing and illustrating a book for their families, inspired by author Todd Parr. Each child contributed a page which reflected who they are and what they care about.

Here are a few examples:

Alex: I love you when you take care of me when I’m sick.

Beatrice: I love you when you snuggle me.

Becca: I love you when you’re scared and even when I’m scared.

Izzy: I love you when you play chase with me.

Eliana: I love you no matter what.

The children already knew so much about the meaning of love – and they made it clear that they wanted love to guide, support, and nurture their friendships. Yet, despite this deep understanding, as humans, there are times when they don’t communicate or collaborate together in productive ways, creating accidental or even intentional problems. They continually bump into each other with their bodies, feelings, expectations and ideas.

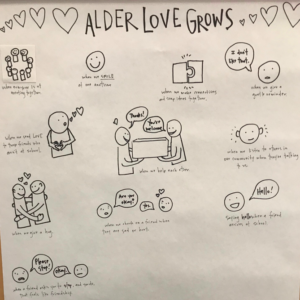

To support these unpredictable moments, we invited the children to create classroom agreements. This living document is a tool for all of us to reference throughout the school day. As love researchers, we framed our classroom agreements in terms of how to grow our Alder love:

And how to break our Alder love:

We noticed that they were still grappling with putting into practice what love looks like, sounds like, and feels like. When we introduced cardboard and tape, we wondered what they might create. How might these new materials inform our investigation of this abstract, yet tangible, feeling?

Eliana sat down at the Maker Studio and announced, “Materials, I love you. They can turn into love if you give them away.” Eliana picked up blue tape and began stretching and cutting pieces of it to wrap around two chunks of cardboard. She looked at me and said, “You’re not going to believe what I’m making. I’m always making something amazing.”

A bit later she stood up and said, “I made a love finder! Look for love around the classroom.”

It was something amazing! I invited Eliana to bring her Love Finder to our reflection meeting. She joyfully offered her community a chance to try it. She said, “You look for love all around. Do you see love?” Kellen, the one who launched our love investigation, was sitting beside her. He held the cardboard creation close to his eyes and looked across the room, then responded flatly, “Nope, I see the same thing.”

In this moment, Kellen offered us a new problem as Eliana offered us a chance to look for love with intention. She pushed us to consider how love has different forms: There’s unconditional love (remember the gift she gave to her family – I love you no matter what) and there’s the kind of love that we might need a Love Finder to see. She offered us an invitation to shift our mindset. This “Love Finder” became an provocation for our whole community, and it inspired a bunch of other love tools such as “Love Binoculars”, a “Love Collector”, and a “Love Machine.”

Sometimes the teachers see a gap and intentionally create a problem by sharing a noticing or wondering to challenge the children’s thinking. During Partner Explore, Emmy and Kellen were working together in our Maker Space and collaborated on a “Love Case”.

It has blank pieces of paper in it which they give to friends who are feeling sad. Emmy explained when friends holds the paper against their hearts, it makes them happy. As she was sharing their thinking — their early attempt at creating a tool to replace sadness with love — I noticed a disconnect between the list of actions which help our Alder Love grow (“smile at a friend”, “listen to others”, “check in when someone is hurt”) and this seemingly hollow offering.

I felt stuck: Do I step into the world they’ve created where the “Love Case” can heal hearts, or do I intentionally create discomfort and uncertainty? Based on my relationships with them and my beliefs in their capacities, I carefully chose a piece of paper from “Love Case” and held it to my heart as Emmy watched with pride. Then I leaned over and said, “I don’t feel anything.” She immediately tried it for herself and after a moment of feeling love transmit from the paper to her heart she said, “I do, it works! I feel happy.”

I wasn’t sure how much I could nudge her, but I was curious about where her edge may be – so I said, “I notice the paper is blank. I wonder how will others will know there’s love in it?” She turned back to her partner and they began discussing adding scribbles with a red pen and making hearts.

It’s clear that this unanswerable question, What is love?, holds the qualities that we need to engage and connect our entire learning community. As Emmy stood at the edge of the gap, I was right beside her feeling unsure yet curious. As a community, we already know so much about love, yet its many dimensions and nuances remain a mystery.

Four-year-old Eliana talks about the gap this way:

The most important word is yet. It means you can’t do something now. It also means that you can do it later, but you just need to practice! Practice means that you keep doing something over and over until you get it. It feels good to practice, to me it feels loving. And it makes me feel strong next to my heart. I can’t do handstands yet, so I practice. Like, practice being upside down with my hands, with my feet in the air. Sometimes I fall down, or I can’t get my feet up. I just try again, or I say “can I please have some help?” and I feel more love.

In Alder, we’re still living in the yet. We’re still trying to figure out this idea of love outside of our families, and what happens when my ideas are different from your ideas. We’re exploring our early attempts at making sense of mixed up feelings and constructing (and revising) how we want to be as a community. Yet, these stories are evidence of how a community of children and adults can create the world in which they live, learn and love.

I’m curious:

How might we create learning environments and experiences rich with conflicts and problems?

How might we think about them not as obstacles or nuisances, but as opportunities for uncovering more about ourselves and each other?

How might solving problems together support children to grow their sense of empathy and agency?