Working on Whiteness

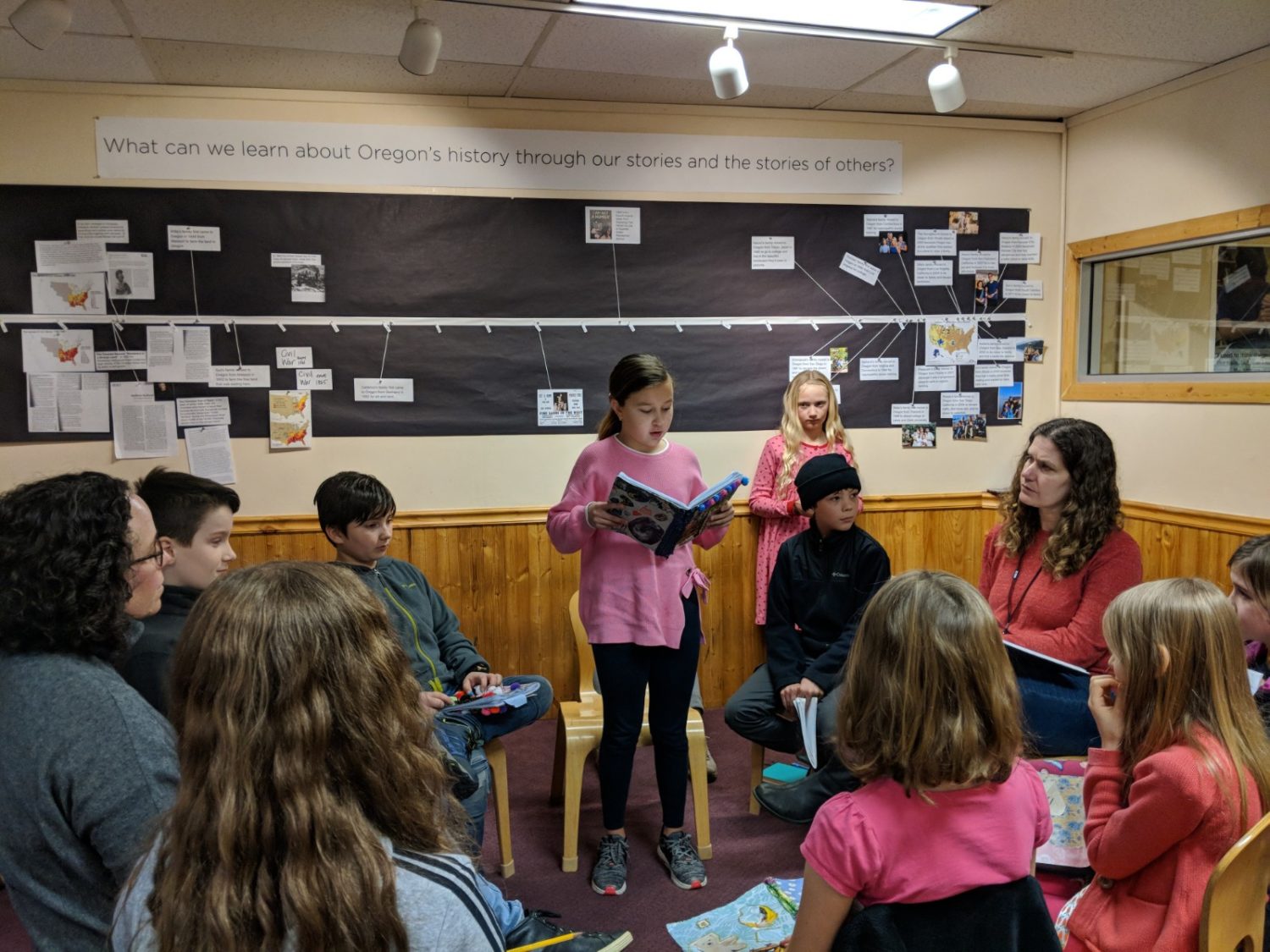

Have you read the book Not My Idea by Anastasia Higginbotham? Several weeks ago, Higginbotham dropped by Opal School to speak with the 4th and 5th graders in our Willow classroom. She joined us there to talk to us about Whiteness. The children were ready for her.

They were ready because the teachers had been working with the children for months to make sense of Whiteness and White privilege and racism as part of their intended Oregon History curriculum.

The children had considered questions like:

- What’s the problem with perspective?

- What is the impact of decision making and how does it depend on those who are “at the table”?

- What context does the story of the Oregon Trail sit within?

- What do we need to understand about the land that our school sits on — our homes?

- What is the “master narrative” and how does it work?

- How does the “master narrative” protect Whiteness?

- How do you benefit from the “bad ideas” that have developed Whiteness over our history?

- Where did Whiteness come from?

Schools, of course, need to teach history. At Opal School, our intentions are to support children to explore the big concept of perspective-taking and we use historical frames to do so. This year, at Opal School, every child in this particular classroom benefits from White privilege– including the privilege they have to live and to go to school on land that was taken from someone else. The State of Oregon expects us to teach Oregon History to children at this age. So, given all these realities, how could we not have been ready to have a conversation about Whiteness with Higginbotham?

I hope to be able to mention that we are learning about Whiteness and have it land as if I said that we were learning about, well, pretty much anything else. I am confident that I could tell you we were learning about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr,. or Rosa Parks, or even the Indian Removal Act or the Oregon Exclusion Laws and you wouldn’t blink. I imagine you’d be glad to hear it. But what about Whiteness? What about the thing that created all the bad ideas that drove the need for people like Dr. King and Mrs. Parks and so many others to lead with such courage and vision? What does it take to get to the root of the problem and take a hard look at it?

Inside the front cover of Not My Idea, Higginbotham quotes Toni Morrison. “White people have a very, very serious problem, and they should start thinking about what they can do about it.” We’ve been trying to design experiences with the children in order to help them — to help us all — understand better what the problem is, so that we can make some effort to so something about it.

In “Privileged,” NBA player Kyle Korver writes:

What I’m realizing is, no matter how passionately I commit to being an ally, and no matter how unwavering my support is for NBA and WNBA players of color….. I’m still in this conversation from the privileged perspective of opting in to it. Which of course means that on the flip side, I could just as easily opt out of it. Every day, I’m given that choice — I’m granted that privilege — based on the color of my skin.

In other words, I can say every right thing in the world: … I can be that weird dude in Get Out bragging about how he’d have voted for Obama a third term. I can condemn every racist heckler I’ve ever known.

But I can also fade into the crowd, and my face can blend in with the faces of [the hecklers that harass my teammates at games], any time I want.

I realize that now. And maybe in years past, just realizing something would’ve felt like progress. But it’s NOT years past — it’s today. And I know I have to do better. So I’m trying to push myself further.

I’m trying to ask myself what I should actually do.

How can I — as a white man, part of this systemic problem — become part of the solution when it comes to racism in my workplace? In my community? In this country?

How can we support young children who identify as White to become part of the solution, even before they’ve had time enough to understand all of the ways that the problem is baked into our communities and our laws and our country?

Korver continues:

When it comes to racism in America, I think that guilt and responsibility tend to be seen as more or less the same thing. But I’m beginning to understand how there’s a real difference.

As white people, are we guilty for the sins of our forefathers? No, I don’t think so.

Or, as Higginbotham writes, It was not our idea.

Korver continues:

But are we responsible for them? Yes, I believe we are.

And I guess I’ve come to realize that when we talk about solutions to systemic racism — police reform, workplace diversity, affirmative action, better access to healthcare, even reparations? It’s not about guilt. It’s not about pointing fingers, or passing blame.

It’s about responsibility. It’s about understanding that when we’ve said the word “equality,” for generations, what we’ve really meant is equality for a certain group of people. It’s about understanding that when we’ve said the word “inequality,” for generations, what we’ve really meant is slavery, and its aftermath — which is still being felt to this day. It’s about understanding on a fundamental level that black people and white people, they still have it different in America. And that those differences come from an ugly history….. not some random divide.

It is an ugly history. We don’t do children any good if we don’t teach it to them that way. We don’t do our communities any good if we don’t take responsibility for teaching it to them as complicated and full of tensions. But then we have to help them think of things they could do to make it better — to solve some of these problems — to take responsibility and to make a difference. We can give them practice and permission and encouragement to take that on. They want things to be better.

More from Korver:

This feels like a moment to draw a line in the sand.

I believe that what’s happening to people of color in this country — right now, in 2019 — is wrong.

The fact that black Americans are more than five times as likely to be incarcerated as white Americans is wrong. The fact that black Americans are more than twice as likely to live in poverty as white Americans is wrong. The fact that black unemployment rates nationally are double that of overall unemployment rates is wrong. The fact that black imprisonment rates for drug charges are almost six times higher nationally than white imprisonment rates for drug charges is wrong. The fact that black Americans own approximately one-tenth of the wealth that white Americans own is wrong.

The fact that inequality is built so deeply into so many of our most trusted institutions is wrong.

And I believe it’s the responsibility of anyone on the privileged end of those inequalities to help make things right.

Investigating the history of the Civil Rights Movement – or Oregon History – or Colonial History – creates an opportunity for us to see Whiteness. It’s time to draw a line in the sand. It’s time for White teachers, like all people who benefit from Whiteness, to take a really hard look at what they can do. Because we’ve got a very serious problem and we need to take some responsibility for it.

What happens when we teach a history that obscures the stories of so many – or that teaches about triumphs and heroes in such as way that it breaks the patterns we still suffer from today? What does it matter what the children in our classrooms come to believe?

How do we take responsibility for the citizenry we are shaping? How do we learn to admit that we have a problem because we are part of a system that is hurting people?

How do we support one another to be less afraid of Whiteness and White supremacy so that we can talk about it, bring it to the surface, and send it away — learning to believe that we don’t need it anymore and coming up with ideas to do things differently? How can we help children and ourselves learn to see our racism — to identify it dispassionately, as a symptom of having grown up in this society at this time — and learn to ask questions about it — learn to stop denying it because it wasn’t our idea and start asking, instead, What power do I have here to do something differently? What is my idea?

Higginbotham was honest with us, and encouraged us to be honest, too. She said, “It is complicated. And you have to tell the truth about that.”

Future posts will discuss actions being taken with and by the children to support this effort.

I. LOVE. THIS. POST. Best line: “How can we help children and ourselves learn to see our racism — to identify it dispassionately, as a symptom of having grown up in this society at this time — and learn to ask questions about it — learn to stop denying it because it wasn’t our idea and start asking, instead, What power do I have here to do something differently?” Thanks, Susan, for your courage and leadership and commitment to a better future.