What are the children teaching me?

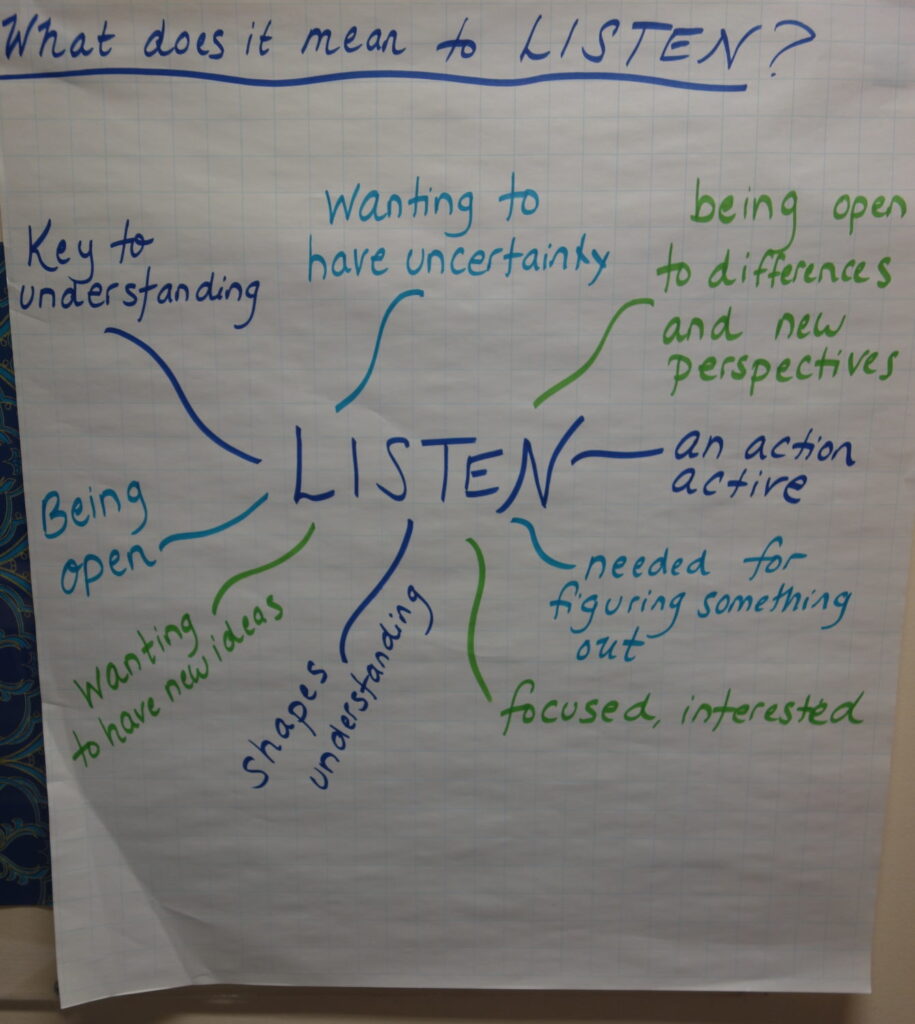

As a student teacher in Opal 3 this year, I continually find moments where my own growth parallels, intersects, is inspired by, and connects with the children’s growth. One instance where I experienced this was when the children began to unpack what it means to “listen to understand” vs. “listen to reply.” As a community we wondered about this quote by Stephen Covey:

“Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply.”

I observed the children play with their ideas about these different types of listening, construct understanding together, draw connections, and think metacognitively about their listening habits. As I’m learning often happens when I’m committed to wondering with children, the children nudged my own learning edges pertaining to listening.

One child – who I will call “Bill” – specifically pushed my thinking regarding what it entails for a teacher to listen for understanding. This year, Bill and I experienced a shift from the playful relationship that we had last year, when I was an assistant. As I began to teach in Opal 3, I sensed Bill pushing back against many of the invitations I offered the children. I also noticed an increase in behaviors that I worried impacted other members of our community and, admittedly, left me feeling uneasy.

One child – who I will call “Bill” – specifically pushed my thinking regarding what it entails for a teacher to listen for understanding. This year, Bill and I experienced a shift from the playful relationship that we had last year, when I was an assistant. As I began to teach in Opal 3, I sensed Bill pushing back against many of the invitations I offered the children. I also noticed an increase in behaviors that I worried impacted other members of our community and, admittedly, left me feeling uneasy.

We checked in often about this. At the time I was convinced that my intention during our check-ins was to uncover what was going on for him. I would ask questions like, “what’s going on for you when you do/say X?” and “what can you do next time to stop yourself before you do X again?” Bill would often answer these questions by suggesting strategies that he might try next time. I would affirm his suggestions and we would make a plan for trying a strategy.

When Bill committed to trying a strategy, I experienced a sense of relief because we had a “plan.” If the plan supported Bill in stopping, maybe the behaviors that were feeling so hard for me would not happen again! Maybe the messiness and uncertainty that came with these behaviors would settle. In reflection, I recognize that during our check-ins I was listening for opportunities to encourage Bill to name strategies because, when he did this, it made me feel better.

I have since realized that I was experiencing something that listening researcher Andy Eklund describes as “confirmation bias.” He explains that people have confirmation bias when they listen to “pick out facts or aspects of a conversation that support pre-existing beliefs, values, or perceptions.” In this case, my perception of Bill’s behaviors was that they were disruptive. I saw them as separate from who Bill was as a person, but struggled to understand their origin and believed that they needed to stop. Rather than listening to all of what Bill was saying to me with the intent of truly hearing him, I listened for and picked out the pieces of dialogue from our check-ins that reinforced my belief that Bill’s behaviors were disruptive and needed to stop. It’s not surprising that we were stuck.

My thinking shifted right before Spring Break when Bill told me something about himself that I had not heard before. He said:

“I don’t know why, but it’s just a ‘thing’ for me to be hard on new teachers at Opal.”

This fascinated me. How had this come to be? What did he mean by a “thing?” How did he perceive himself in relation to this “thing”? Luckily, I had all of Spring Break to wonder about and reflect on this nugget Bill had offered.

I did so primarily through journaling and reading. The morning pages (from The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron) have become my go-to method for decluttering my thoughts. I filled my morning pages with curiosities, worries, and beliefs about this “thing” Bill had shared with me.

Often I reread my own writing after I finish in an effort to identify patterns of thought. Each time I did this, I was confronted with my own confirmation bias. The pieces of our conversations that I zoomed in on directly supported my beliefs about Bill’s behavior, what I thought motivated this behavior, and why. For the first time I saw that I needed to make a change. Unsure of what might happen, I began to experiment with forming questions about Bill’s behavior rather than beliefs about where it was coming from. What about what Bill was doing made me curious?

Gradually, my questions grew in objectivity and I felt myself shifting. I wondered: How does something become a “thing” for Bill? What is my role in this “thing” Bill has noticed? What is the relationship between Bill’s actions, values, and beliefs? How does Bill feel in our relationship?

I remembered one of Hannah’s blogs from earlier in the year where she wrote: “Children are very good at telling us what they want. However, if we listen and observe carefully, they can also show us what they need.“

I began to wonder what Bill was trying to show me. If my own agenda was no longer in the way, what might Bill reveal about his needs? What could I learn from him? Diving into these questions meant that I had to be keenly aware of my own confirmation bias so that I could listen to him for understanding.

After Spring Break, Bill and I checked-in again. This time I embraced vulnerability and shared with him that I was worried I had not been listening to understand him. I asked him to share how he felt in our relationship and, as he spoke, I practiced the metacognitive listening strategies that Opal 3 had been practicing for months. This freed up space for me to notice that Bill often used the words “great” and “hard” when he was talking about our relationship. We wondered about these words together. Did we have the same ideas about what was feeling “great” and what was feeling “hard” between us?

Stemming from this conversation, Bill and I collaborated to design a reflection sheet that we committed to filling out together before dismissal each day. The sheet provided space for us to share those “great” and “hard” experiences and pushed me to practice listening for understanding as he shared moments from his day. Often I was surprised that my assumptions about what would feel “great” and “hard” for Bill on a given day were not what he recorded. As I continued to practice listening for understanding, I sensed our connection deepening and those behaviors from earlier in the year significantly lessened in frequency.

Earlier this week Bill and I ate lunch together with the intention of reflecting on how our relationship had grown this year. This is an excerpt from our conversation:

Bill: Well, I think when we started at the beginning of the year things weren’t working out very well. But then when we got that thing where we wrote down how our day went it really helped. I don’t know why but it just did.

Sarah: Yeah, I noticed a similar change. How do you think reflecting together shifted our relationship?

Bill: It was kind of like knowing each other more helped. Like listening to how the day went. I think it connects to trust too.

Sarah: Really? How?

Bill: For me, I think, you trust people more when you know more about them. It’s hard to figure out! It just kind of happens! You don’t feel comfortable with, like, saying certain things if you don’t trust the other person.

Sarah: I’ve been wondering about how listening to understand each other built trust between us this year. Do you think they are connected?

Bill: Yeah…like I think listening when we did the sheets together built up the trust.

Sarah: Do you see connections between our experience and other relationships in your life?

Bill: Yeah. Like…usually when I meet someone new I try to avoid them or not be friends with them. And I think I maybe I do that because there isn’t the trust.

Conversations such as this one with Bill would never have been possible if I had not suspended my own confirmation bias so that I could begin listening to him with the intent to understand. Once I was able to set the impulse to confirm my own beliefs about his behavior and need to “fix” them aside, Bill showed me what he needed. He needed to build a relationship with me that was based on trust. He even knew what tool might help us to do this! Setting my own agenda aside created space in our relationship for the true work to begin.

I have found that when I am open to self-exploration in the context of the classroom, the children make me aware of tendencies within myself that I had not noticed before. Being present in this way feels incredibly vulnerable and this vulnerability often comes with discomfort. However, I am learning what a gift it is to be immersed in the discomfort of vulnerability in relationship with children. The children are constantly transforming the lens through which I view the world.

What conditions do you think create safe spaces for teachers and children to grow together?

What conditions do you think create safe spaces for teachers and children to grow together?

How does listening to understand become a natural practice within a learning community?

What role does vulnerability play in the authenticity of learning?

How can we cultivate listening to understand as a habit of mind in relationships?

This was wonderful Sarah! It gave me some ideas to try for deepening my self-reflection about my feelings, reactions, and responses to various behaviors and conversations children have. Thanks!

Thanks so much for reading, Emily and Jane! I would love to hear more about reflection tools you’re exploring. What has worked for you? The Morning Pages have been incredibly meaningful for me and I’m always in search of other tools to try. Learning about myself continues to be essential if I want to be truly present, vulnerable, curious, and learn with the children.