The Possibilities of Loose Parts

When you enter the classrooms of Opal School you will be met with familiar materials that you might expect to see in a lot of Early Childhood and Primary classrooms. You will most likely see blocks for building, colored pencils and markers for drawing, tempera paint and watercolors for painting, and costumes and dishes for dramatic play (or pretend play), just to name a few.

If you then look closer, you will also see a collection of interesting materials peppered throughout the room. Individual, plastic containers that hold ordinary materials like corks, rocks, paper, buttons, beads are offered to bring an invitation of possibilities and of wonder to the children – an invitation to explore and play.

We call these materials “loose parts.” Loose parts can be defined as a collection of tempting and beautiful found objects that children can move, manipulate, control, and change while they play. These loose parts can be anything and come with no specific set of instructions and can also be used alone or combined with other materials (Hewes 2006).

British architect Simon Nicholson used the term “loose parts” in his article, “How NOT to Cheat Children: The Theory of Loose Parts.” In his article, he defines loose parts as materials that can have many properties and that can be moved and manipulated in many ways. He theorized that the richness of an environment depends on the opportunity it allows for people to interact with it and make connections.

We see evidence of this everyday and have documented the vast learning experiences that can occur when children are able to invent, create, explore, and rearrange with loose parts. With no specific set of directions, these materials can become anything – a ship, a jungle, the family’s camping trip, or outer space. They become stories, ideas, feelings, and thoughts. They become a world full of open-ended possibilities.

Loose parts are found all through our classrooms and can be used throughout the day for exploring a variety of topics, curriculum, and interests. Story Workshop, one structure that we have at Opal School to support literacy, is a time of the day that naturally invites the flexibility of these loose parts. The children are invited to use the various loose parts and materials to find, create, tell, and revise their stories. The parts can become anything and they can serve as a way to create images and pictures to accompany their words and language. We know that there is a powerful connection between images and words, and the loose parts provide children with rich opportunities to create these images and to play with them again and again. The more clear the images become in the child’s mind, the more accurately the words they use express their unique interpretations of their experiences in the world.

In the beginning of the year, we saw how loose parts can have a transformative effect for a child when supporting the creating, crafting, and sharing of stories. M.R., a kindergartener, entered our learning community full of stories, ideas and theories. Yet, when we invited him to tell his stories with traditional pen and paper, he struggled with getting started and transferring his stories in this way. Blank pages seemed to be a deterrent for him, so we couldn’t wait to introduce him to materials as a way to help him find and tell his stories. We were sure that they would help with his block.

But then, on the day that we began introducing materials to the children as a way to help them find, tell and play with their stories, M.R.’s reaction was the same as it was to a blank page. He was unable to move past the beginning. He was having a hard time getting started. We wondered together: What other materials could help him spark an idea and story? What special treasure could be that bridge from stuck to inspired?

Just then, a friend asked if they could bring the small rubber animals to the collage table to help with their stories and M.R. perked up right there. He ran to the basket and came back with small dinosaurs, the perfect characters of the story he wanted to tell. With the characters in place, the other loose parts were able to move and form and dance as he shared his story with his friends next to him.

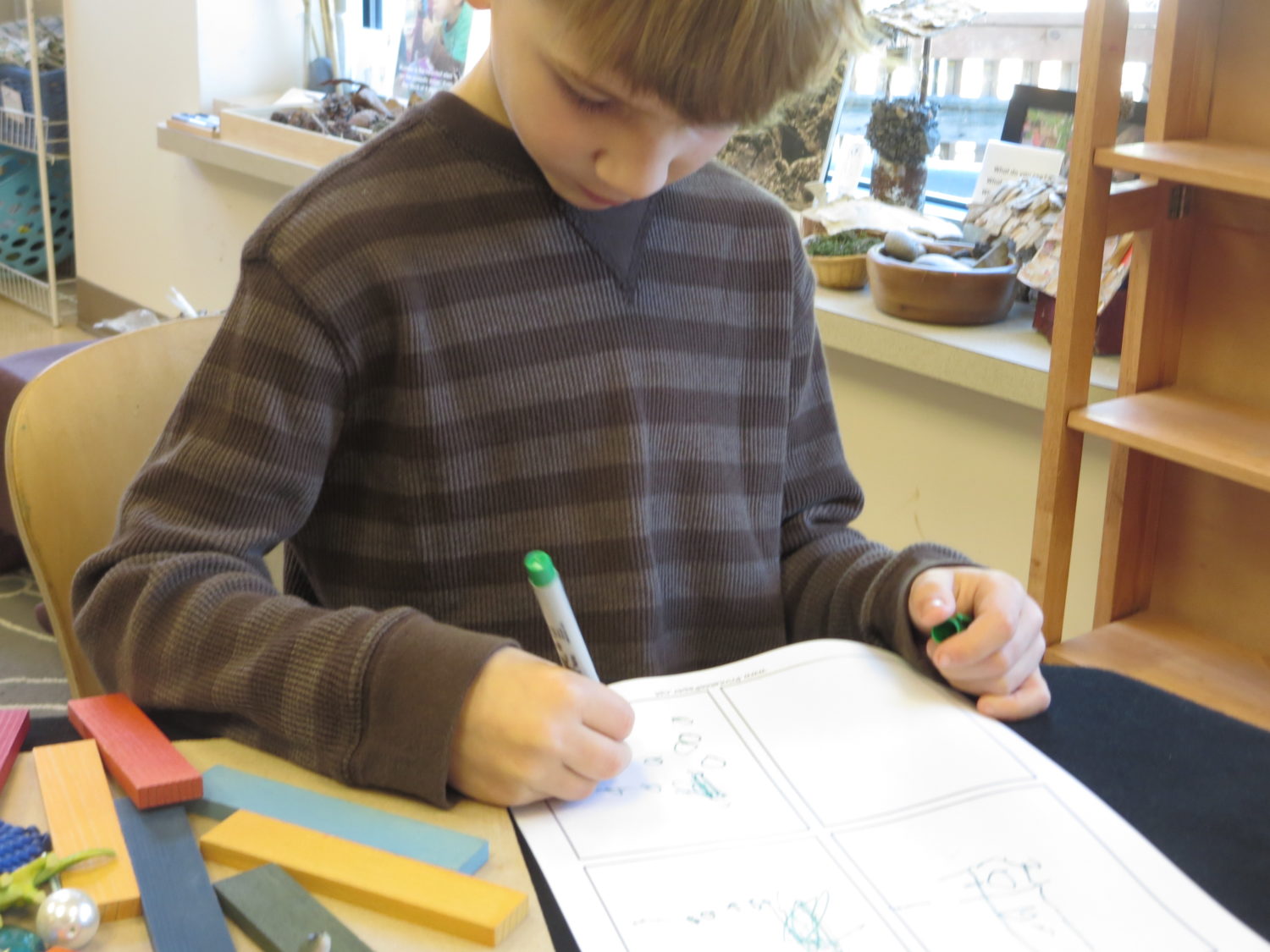

After some time of using materials in this way, it seemed like a natural transition for M.R. to capture his story through drawing and writing. He gravitated to the comic book paper where he was able to use multiple boxes to show the progression and movement of his active stories that he had been playing with in loose parts.

We were able to capture one particular story that M.R. drafted, created and shared in loose parts.

y

y

“A animals made a fort. The cannons fought it. This is it blowing up. But some are still there. And they blowed up again. It was gone. The animals is running. The End.”

After he shared, we then asked M.R. to also share his process. We asked, “How did you find this story?”

“I just thinked about it and there was this [the image in loose parts] so I just write it down. So I knew what the pictures were going to look like. So, you know why these things are spread out? That’s when it blew up!”

In this interaction, we are able to see the excitement and sense of agency M.R. has towards his story. He wants his audience to know his ideas and is eager to share how he got those ideas, too. He is beginning to understand that playing and putting marks on paper, in combination, are a way to get his ideas out into the world. He is also able to articulate metacognitively how the materials were there to help him visualize and articulate the ideas, images and story that live inside of him. We now can see that the loose parts hold endless possibilities for M.R. we expect that they will continue to serve as a vehicle for him to capture and transfer the stories he wants to tell.

We are interested in what connections you are seeing for children around loose parts and found objects. For educators, we wonder: How are loose parts used in your learning community? What do you notice about how the children use these loose parts in their play and work? For parents, we wonder: Where do you see your child’s connection to loose parts visible in the play outside of school?