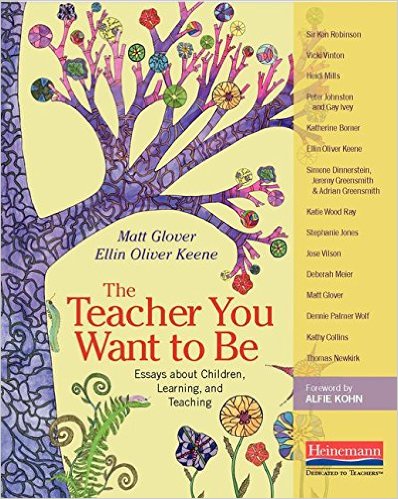

The Teacher You Want to Be

Tomorrow, Heinemann publishes a new book. The Teacher You Want to Be: Essays about Children, Learning, and Teaching, is filled with essays by thinkers whose work has inspired ours at Opal School. With contributions from people like Sir Ken Robinson, Vicki Vinton, Heidi Mills, Peter Johnston, Ellin Oliver Keene, Katie Wood Ray, Matt Glover, Deborah Meier, Thomas Newkirk, and Alfie Kohn (amongst still more wonderful folks), the list of authors closely parallels some of the most played records in our jukebox.

Our relationship to this book sits at its core: Mary Gage and Susan participated in the study tour to Reggio Emilia and the set of “Belief Statements” that followed from the trip that inspired the text. In its published state, the book doesn’t include essays from either Mary Gage or Susan; instead, it is Opal School students themselves whose work turned it from a fine anthology into a beautiful collection.

In 2009, the fifth graders’ gift to Portland Children’s Museum was Cycles and Patterns of Nature. From that artwork, Heinemann’s team created not only the cover of the book but weaved the piece throughout the publication. They also published the students’ statement about the work, in full, as the frontispiece of the book.

When you hear someone mention the cycles and patterns of nature, what do you think of? I know when I first heard the idea, I couldn’t think past tree stumps and spider webs. But I knew that couldn’t possibly be all.

As we went deeper into this project, we have found out it isn’t. The veins in leaves, the curl of a brand new fern, the patterns in a butterfly or dragonfly’s wings, the center of a blossom, and the designs of a snowflake are all patterns of nature and a part of the cycle.

During a hike one day after we’d begun this project, we sat together outside and used our senses to listen to the sounds of nature, touch the bark or grass we could reach, see the patterns in the clouds, on a leaf, or in the dirt, and smell the fresh air of the upper meadow. Back inside the classroom, we were inspired to create our own images of what we’d experienced with our senses.

We discovered that one image could become another, and we were so curious to see if we could do more. An icicle became a point on a snowflake. A pinecone became the center of a sunflower. An acorn cap turned on it’s side became a butterfly’s wing and a fiddlehead fern became the pattern on a wing. A snail fossil became the center of a flower. We found out that even though we think a pattern in nature belongs to one familiar thing, it really belongs to many. It seems that nature is full of connections. You have to expect that the beauty you find in one place will find you again somewhere else.

This idea brings us comfort and makes us feel better as we prepare to leave Opal School. We have made such beautiful friendships here, and if it’s true that these patterns can be found again, we know we’ll have new friends wherever we go next, and we’ll keep our old friends, too.

We offer this gift to the children’s museum in gratitude for all it has given us. We hope these images will inspire the people who see them to spend time exploring nature, so they can find out for themselves how they fit into the world. We hope the images of the seasons remind them of the cycles we rely on and can make us feel connected in our world and with each other.

As an adult, I am surprised by how this worked out. That these efforts revealing the combined power of art, literacy, and play – of the relationships between and amongst a group of people, materials, and ideas – finds such widespread publication is astonishing to me. I don’t know, though, if it will be the least bit surprising for that group of children: They knew that their ideas were a gift to the world that the word needs. Of course others would recognize their power.