Supporting empathy and agency

Opal School is part of the Ashoka Changemaker Schools Network, a group of schools distinguished in their efforts to support empathy and agency. Last year, supported by funding from Ashoka, we held a series of site visits and conversations with three other schools who participate in the network:

- Mission Hill K-8, a Boston Public Pilot School;

- The Blue School, a private preschool through grade 8 (at the time, grade five) in Manhattan; and

- The Brooklyn New School, PS 146, a pre-k through fifth grade public school.

While distinct in many ways, all four schools have found alternatives to the false choice between standardization and disorder. We wondered how considering them through a lens of how each supports empathy and agency might be revealing. The group discovered that the consistent, collaborative effort to find that path is the foundation of how each of the schools develops cultures of empathy and agency. We shared our work at the 2015 Opal School Summer Symposium, along with vignettes from each of the school. As Ashoka’s #StartEmpathy Project generates greater interest through it’s partnership with #ThinkItUp, I wanted to share some of what our group presented to catalyze deeper thinking about conditions where children’s intrinsic desire and capacity for empathy and agency flourish.

One of the things that we struggled to do was to define what we mean by empathy and agency. By “empathy”, we mean the holding of another’s perspective holistically (intellectually and emotionally) and compassionately (with concern for the other’s well being.) Empathy, for our schools, involves a sense of inter-connectedness with that “other” whose perspective is being held: Without that sense of connection, empathy might become by pity.

Connectedness also lies at the core of agency. We saw “agency” as a sense of membership in a community where your gifts offer an important contribution to the health of the larger body. That sense of interconnectedness prioritizes concern for the whole, a value that distinguishes agency from autonomy.

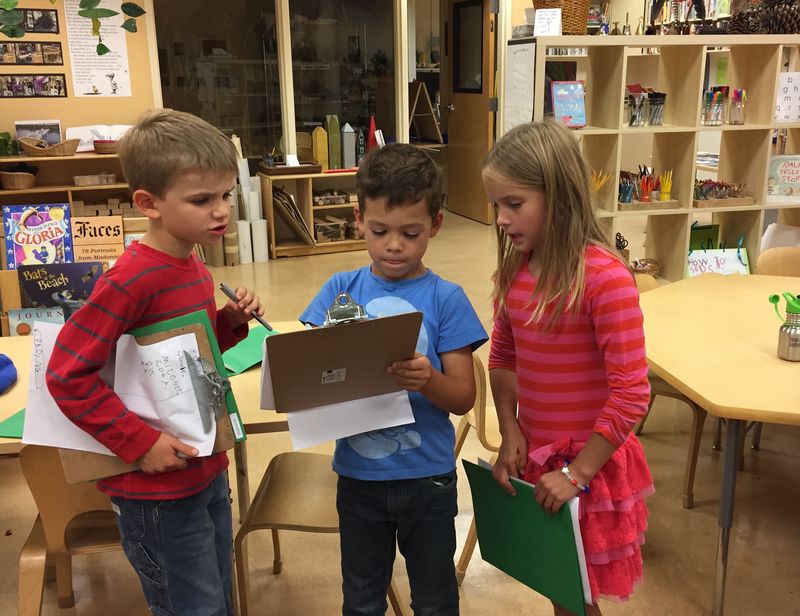

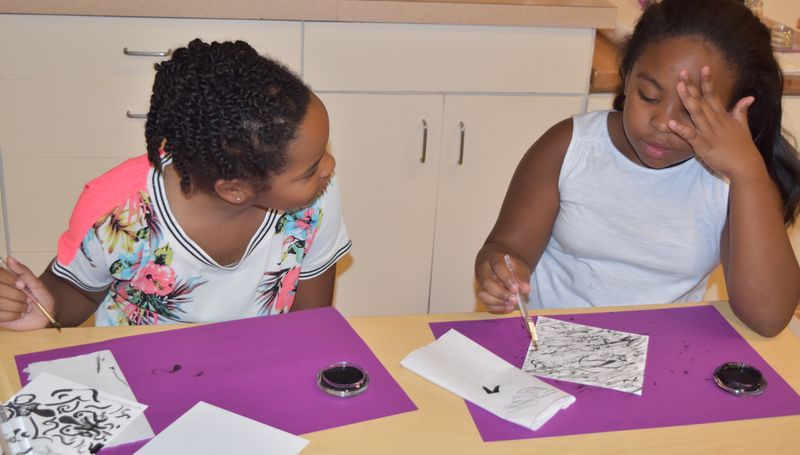

In each other, we saw schools built around the understanding that all children – and the adults who work with them – have the capacity and desire for empathy and agency. Each of these schools strives to create systems that embed these natural desires into all aspects of life and refuses to reduce the incredibly complicated ecosystem of schooling to one part of the day or to a list of “Top Five Ways to Promote Empathy and Agency.” Every day, our work opens new doors to our imagination of what new possibilities can emerge as children and adults learn together. “Top Five” lists diminish the complexity of the relationships – between and amongst children, adults, ideas, materials, and environments – that lead to greater quality in education.

Amongst our small group and in our very brief visits to each other’s schools, we brainstormed the following list of themes related to this question of empathy and agency. Far from a reductive “top five,” each entry contains voluminous images and meaning:

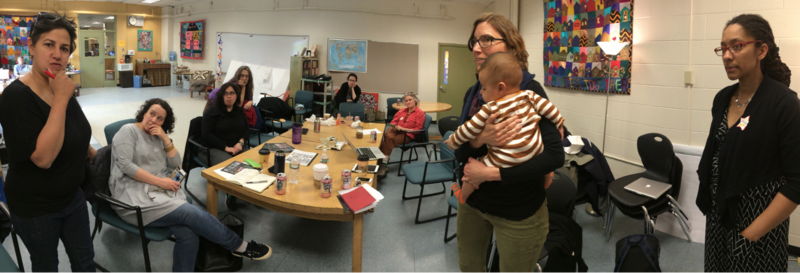

One dynamic that animated our conversations with each other beyond what was visible in the classrooms involved the relationship between a school’s professional staff culture and the experience of students and families. In striving to create schools that present greater opportunities of quality than the ones we remember from our own childhoods, we need practice in relationships guided by values of empathy and agency. In seeking to understand what common practices and principles might exist between the different programs, we found common commitment to inquiry and reflection. Most importantly, staff must be vulnerable and present to each other and the complications of practice. “Everyone needs to be willing to step into the fire together,” said one member of the group, to which another replied, “And there is always so much fire.” The heart of a staff learning community – much like the core of a classroom – is a pedagogy of listening and relationships focused on the big ideas of the work. Agency means recognizing that each staff member’s unique insight and gifts contribute toward making meaning of this complicated work; it should not be confused with autonomy, that suggests that each actor’s independent actions can be independently developed without recognition of interdependence and the critical benefits of collaboration.

I’m curious, dear readers:

How do our definitions of empathy and agency square with yours?

What supports empathy and agency in your schools?

What are the obstacles to developing cultures of empathy and agency in your schools?

How are you working to overcome those obstacles?

My understanding of agency differs from yours…not that you advocate anything I disapprove of…but I would use other words for that.

Agency as I have come to understand it has to do with the self-talk (or self-think) that allows one to keep trying to accomplish something without any erosion. Infants keep after their goals without any insecurity or despair…I’ll do it (pull up to standing, for example) until I get the hang of it.

In early childhood classes for threes we see that some of this agentive behavior has eroded. We meet some threes who are sure they are too little for this new task.

They have learned this lack of agency _from people who love them and try to protect them_ and they don’t want to try, not even with a little help from their friends/teachers/parents.

Overprotective behavior, then, is a cause of lowering of agency. It is antithetical to the Reggio Emilia Image of the Child, which sees children as able to do hard things, and encourages them to do so. There is a bit more agency in my new book, Seeing Young Children with New Eyes: What we’ve learned from Reggio Emilia about children and ourselves, written with Leslie Gleim, which you can find as an e-book on iTunes or Lulu.com and as a paperback on my webpage