How does staying in inquiry sustain collaborative play?

Recently, we offered a new workshop called Constructing Collaborative and Constructive Learning Communities. (Here’s a preview and a recap.) When looking for a story to share from our preschool classrooms, we were on the hunt for something unexpected yet accessible focused on the interplay between the conditions we create for teaching and learning and strategies for cultivating a strong sense of agency and belonging (in children and adults). When Hana told us this story about Walter, we were so eager to share it with our visiting educators!

This is a story about the power of asking questions, the power of documenting children’s thinking, and the power of reflecting on our experiences — and the quality of the relationships that result from these critical practices.

As you read it, we invite you to pay attention to the habits of mind that Hana practices when she felt stuck or challenged. When is she leaning into inquiry? Where do you notice that she’s taking a risk to be vulnerable? What conditions do you imagine might support someone to ask these kinds of questions or write this kind of reflection? And finally, where do you see evidence of transformation?

The remarkable part of this story isn’t what four-year old Walter did or said. We know that children do and say amazing things everyday! What is significant is this teacher’s attitudes and dispositions in the midst of uncertainty. In her first few weeks at our school, Hana got stuck and earnestly turned to a child for guidance. It’s often been said that the best way to learn about children is from children. Hana discovered this idea through her own curiosity and research …

Many of our friends in Cedar are experiencing the joy of a school community and peer connection for the first time. The experience of collaborative play and the opportunities that live inside of these interactions are at the forefront of our planning in the first months of school. I find myself reaching for connection to the children in my own interactions and, as they share their stories, our classroom overflows with the hope and the abundance of possibility that lives within our community.

Watching the children connect and begin to care for one another feels incredible and deeply celebratory. I see every child as a valuable co-creator of our community and and I yearn for all of their stories to each be a part of Cedar. When watching some friends experiment with collaborative play, I began to notice that some children have more practice sustaining cooperative play. I wondered what approaches to play the children who had more experience were using and what strategies they relied on when they were playing with others.

As I review my daily reflections from earlier in the year, I find myself taking the approach of a ‘problem solver.’ I would place myself closely to children who were often exiting play, so I could support when play became problem-solving or socially challenging. When listening to their play as ‘problem solver’ I felt like I was stockpiling the content of their dialogue. My intention in listening was to find connections that I could jump in and share when the moment of conflict arose. In that moment of contention I would try to sustain the play for them. Some examples of what I might have tried include offering language to support the negotiation, providing the children with sharing strategies such as counting, or defining spatial boundaries for them in their play. I would also try to create connection by stating how I knew of a shared interest. These moments felt meaningful to me in the moment, but the children did not really engage as deeply with the connections as I had hoped for. The children would listen and consider what I was suggesting and even repeat it. They would listen to the information I provided about their peer and they would acknowledge the shared interest, but that didn’t move the play forward.

Here is a small excerpt that shows me offering a shared connection and it misfiring:

Sam is playing with the magnatiles independently when Blair approaches.

Sam: Don’t take my pieces! I am building a spooky express!

Me: Sam, did you know that Blair told me she also likes spooky things!?

Sam: Oh…She can build hers over there. I am building the Spooky Express here and she can build it there.

I began to wonder if it was only the relationship I held with the children that gave them reason to listen and consider. In that moment what I was doing was supporting the children in listening to another child, slowing down, and essentially shifting the focus away from their imaginative play. They acknowledged the information I had given to them and agreed that they had a connection, but that connection was not authentic or meaningful to them. The connection I created was just providing them with more information. Some children adopted the vocabulary I was using around interactions and that did decrease some hurtful exiting strategies used by children. An example of this was there seemed to be less grabbing and running away, and more asking for materials. There also seemed to be a tendency for children to just agree that they weren’t going to be able to play together, so they moved away from each other and continued to play independently.

In my daily reflections I kept noticing that the attempts I had been making around collaborative play were not leading me to solutions that supported authentic connection. I was supporting them, making it easier for them, but my role of ‘problem solver’ didn’t solve problems in a way that resulted in collaboration. Often times this approach made it safer for children to exit and play alone.

It was time to try something new – or go back to the drawing board, as we often say in Cedar. I started to reflect on friends in our community who sustain play for a long time. What treasures did they hold within their language, in their movements, and in their way of play that made them so skilled in collaboration? I decided to take the time to listen to their interactions and learn from them. I carefully and diligently transcribed conversations and listened to our friend Walter play over a few days. I had selected Walter to listen to because I had noticed he will play anywhere in the room, plays with many different people and materials, and needs very little support when he finds himself in conflict during social play.

One of the first things I noticed was that transcripting conversations was allowing me to listen in a new way. I was no longer listening for what the children had in common, or with my attention on creating an equitable environment where everyone had exactly what they needed. I was listening for how children connected authentically to each other and created meaningful play in the midst of uncertainty. I wholeheartedly embraced the challenge of connection by being present with the intention to learn from the children’s natural play strategies and not to problem solve. What I uncovered felt both surprising and intuitive. As Walter played, he successfully navigated rejection, fixed mindset, and invisible boundaries. I was astonished by his persistence and resilience and was fascinated by an aspect of his play–inquiry. When I looked at the transcripts, I noticed Walter was living in inquiry. He was able to navigate these complex social situations in many ways, but two of the most reoccurring ways he sustained collaborative play was in his ability to ask questions and in his dedication to communicating his own boundaries. He clearly communicated what was non-negotiable and was open about what he calls his need for, ‘rules that make sense.’

Walter’s transcripts were full of sentences that ended in question marks. He often made suggestions that were open for his playmate to engage with. He approached play as connection, and connection to Walter’s is entangled with being willing to ask questions even when it is risky.

Here is a very small collection of his questions that I documented:

Can we try?

Does that work?

Can you share so we both have one?

What is your idea?

Are you building a tower?

Where can I put my pieces?

I need some paint, can I borrow some of yours?

Can you show me how you did that?

Here is a very small collection of his boundaries that I captured in the transcripts:

You can break anything, but not this house

They can be bad guys over there, but they will not come over here

We can share these, because we both need them

You have many, and I have none, so you have to give me some

When considering Walter’s questions, I realized that sustaining play didn’t depend on him using a singular strategy to problem solve during conflict. Walter’s play was sustained by his mindset of looking for connection, flexible thinking, and being willing to embrace uncertainty by living in inquiry. I was reminded by Walter’s play that authentic connection begins with having to enter uncertainty and speaking it aloud to those around us. Remaining open to inquiry supported Walter’s friends in playing with him because they felt connected to him, and in turn Walter’s felt connected to them. He often celebrated this openly: ‘Look we both have smoke stacks on our trains!” “Wow, we once had a problem, but now we fixed that problem!” He embraced the countless possibilities for collaboration, continuously clarifying his own needs and ideas for play, celebrating their successes and transformation along the way.

When I was the “problem solver”, I had been holding tightly to certainty and to power. Through documentation, self reflection and transcripting conversations of my students, I was able to lean into uncertainty and learn from the true masters of collaborative play–the children. If my intention was to support children in connecting authentically and developing skills of collaboration, I would need to reframe my own practice of being the problem-solver. My role as problem-solver had been dissolving any possibility for collaboration or authentic connection, the foundation of Walter’s play. If anything, by providing only problem solving strategies, I was creating an environment of certainty and safety. An environment which gave them little or no time to practice the type of authentic negotiation that results in collaboration, connection, and transformation.

Looking to the future I am intentionally embracing the uncertainty of conflict in social play. I have begun to replace my problem solving strategies with inquiry and am excited to see how this may may nudge students to imagine conflict and confrontation as the opportunity to co-create an abundance of possibilities. Some of the questions I will be asking them are:

Can you share your plan/Have you told your friend your idea?

Can we imagine another way?

How can we snap these ideas together?

What would help us continue to play all together?

Does anyone need anything for us all to be able to play?

How can we make this feel more like friendship?

Some of my wonderings as I continue to reflect on my own practice are:

What language do I use during conflicts that is supportive of collaborative play?

What habits of mind are practiced when I am listening to children learning to negotiate?

When children communicate nonverbally to me during play, what possibilities do I have to support their message?

What language supports their connections?

I am so curious to hear how others create possibilities for children to engage in social problem solving and collaboration!

- What types of questions do you use to support children to listen to one another in times of conflict?

- What language have you noticed supporting authentic connection in times of disconnection and misfire?

- What do you hear children saying when negotiating in collaborative play?

Hana- I love hearing your process. This is such a great example of what it means to be a “teacher-reseacher.” Thanks for the sample questions that you will now use with the kids. I’m going to use this one at home when my kids are squabbling: “How can we make this feel more like friendship?”

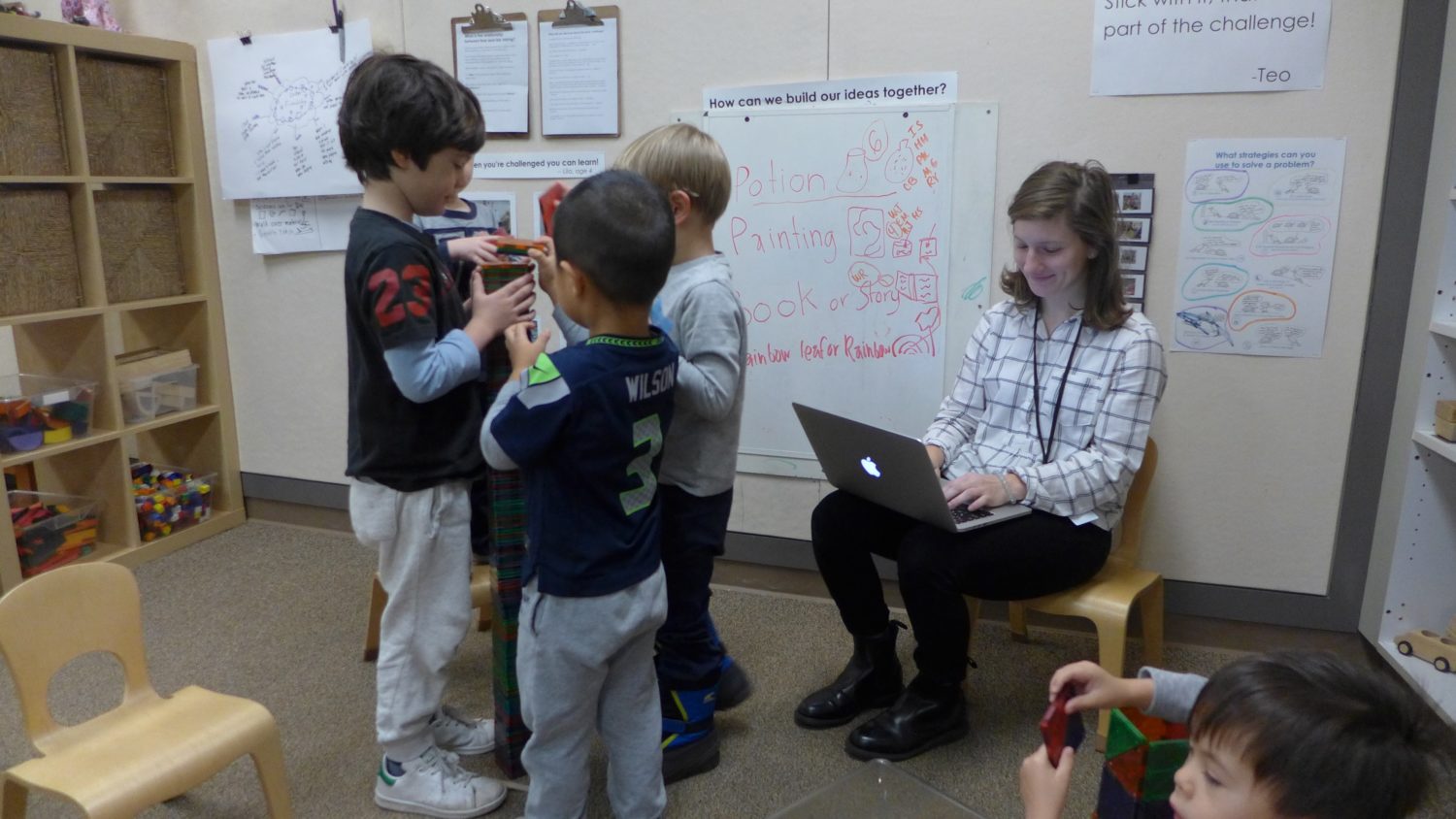

Hi Hana, I really enjoyed hearing about this whole process you went through and are still going through. It is one we can all relate to as educators. I was wondering how you physically did the transcribing of the conversations? Did you have your computer with you and you typed as fast as you could while you observed or did you record audio or video and then transcribe after the fact. I am trying to capture the language that children in my class are using during play times and am finding it a bit of a challenge to get it all down! I hope things are going well for you and your class! Thanks!

Hi Emily! I predominantly use my computer to transcribe the long conversations. I also transcribe from audio/video or with paper and pen depending on where I am and the intention of the documentation. I found that it felt lighter to try on transcription, when I was focused on a small group of children, who were actively playing with a material.

Thank you for sharing a bit of yourself through your practice, and thank you for these incredible questions to be asking the children, and questions to reflect on in my own practice.