Pedagogical approaches and their political implications

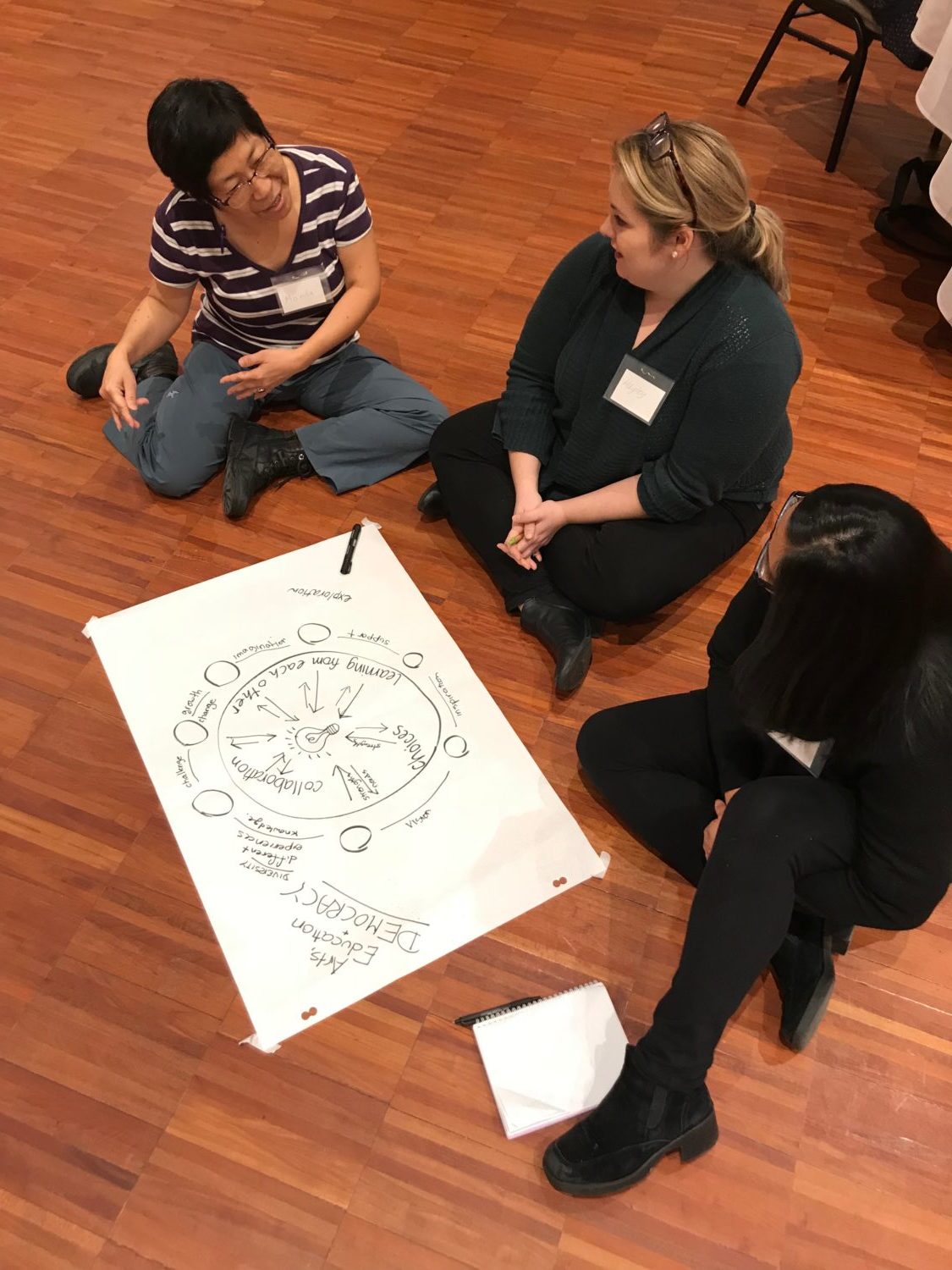

Opal School led professional development workshops in Vancouver, BC last week. They were rich opportunities to connect and develop new ideas with educators in a region that has been inspired and transformed by Opal School’s work.

Our second day’s session focused on play, the arts, and education for democracy. Before considering the role that play and the arts might have in preparing people for participatory democracy, we asked teams of participants to envision the characteristics of an educational system designed to sustain fascism or authoritarianism. How might we frame the “core competencies”? What pedagogical approaches might best support their growth?

Little did I imagine that this thought experiment would bring about strong memories for some in the group.

A woman from Kazakhstan said the question sent her right back to her years in school. When the suggestion was made that her experience must have felt oppressive and alienating, she pushed back: I had a very happy childhood, she explained. I always felt safe. School was a place where you learned what was right and what was wrong.

A man who had grown up in Iran said that he thought its most forceful characteristic was a systematic and sustained attack on the imagination.

Anti-democratic cultures want the best for their children. They are guided by their sense of what is true and good and beautiful – and what is dangerous and wrong and ugly.

Some school systems place highest value on efficiency, certainty, security, and standardization. There are other possibilities that have different consequences for civil society.

What do you think are the skills and dispositions that will best support people to participate in and extend democracy? What are the pedagogical approaches best situated to foster those skills and dispositions?

Ah, this is such an exciting question! I have been diving into the concept of pluralistic learning approaches ––learning approaches that seek out active engagement and dialogue with others without the pretense of coming to a collective understanding. In the spirit of Rinaldi’s “dialogue among differences,” the idea is not simply that a multiplicity of possibilities and perspectives are tolerated, but that encounters with these, the “other,” are necessary and even desirable.