Materials as Metaphors

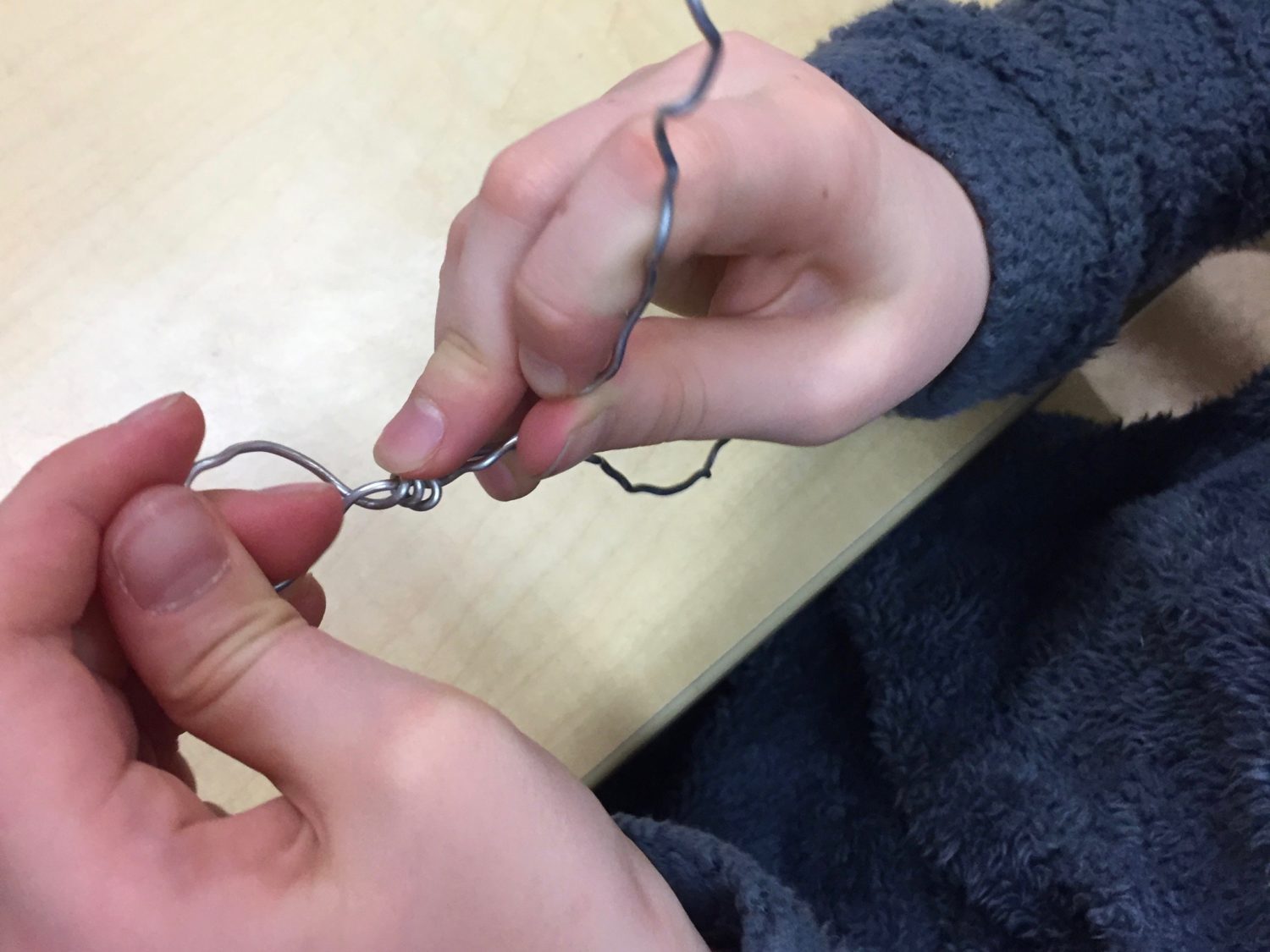

My recent post, Say What You Mean, began as this post — but I got so tangled up in thinking about the relationship between knowledge and meaning and learning and relationship and power and vulnerability that I realized I’d better split these posts in two. In this post, I’ll share the experience I had recently in Opal 4 that got me started down this path, thinking about these relationships, struggling with how to say what it meant to me, and wondering what it will mean to you — knowing that that will help me know more about what I mean to say.

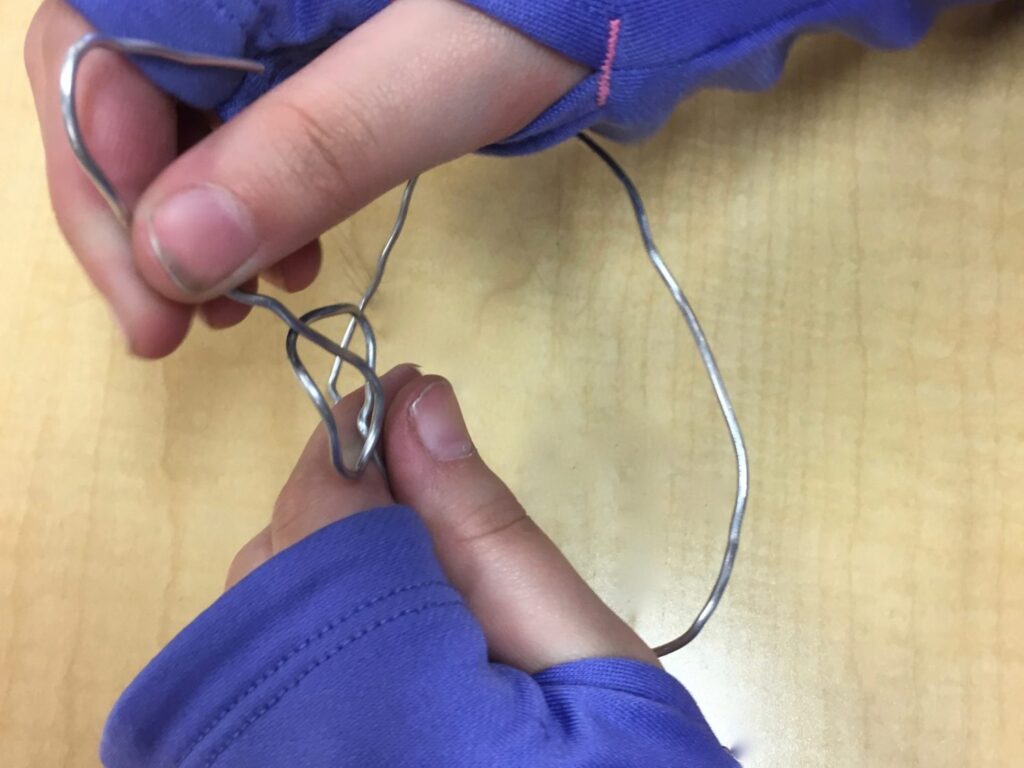

As I wrote in Constructing Identity, Opal 4 has been exploring the concept of identity. What does it mean? How does it work? Why does it matter? It so happened that the week prior to what I’ll share here, Lauren brought an experience with wire to our weekly staff development meeting. She handed us each a length of aluminum wire and invited us to play with it, sharing what we noticed about it’s properties, or affordances. She asked, “What can the wire do?”. The list of “noticings” was long, but one of the them focused on the capacity of the wire to “remember” what it had done. The wire was pliable and cooperative in our hands, but once it had bent a certain way, it was impossible to erase every bump. This reminded me of the conversations Opal 4 had been having about identity. As I played with the wire, snippets of dialogue returned to me. Ginger had offered, “You can’t change your identity. You only can grow it.” And Nate had created the metaphor of the onion — identities are made of layers and layers of experiences. Exchanges like this one had been typical:

Elijah: But if what you said is the truth – that your identity never actually shrinks? Like if your identity never changes – it just grows –

Roan: If you think but you don’t know – that 1+1=3 – that’s a part of your identity – it’s what you think – but then what if you find out that 1+1 actually doesn’t equal 3? That’s taking away a part that’s not adding a part.

Ruby: Part of your identity – when like Roan’s saying – if you think 1+1 = 3 and then you figure out that 1+1=2 then you could say, “I used to do that, or I used to think that” and that is part of your identity.

Nate: It’s still part of your identity – you just erase it – but it’s still there.

Ruby: You just add on.

Materials are metaphors you can hold in your hand. And the wire was feeling BIG in mine– filled to bursting with the possibility of meaning and connection.

So I decided that I would bring the same experience to Opal 4 and see what happened. How would playing with this material support their thinking and deepen their understanding of this abstract concept? Would wire help us move beyond the words themselves, towards a richer conceptualization of the function of individual identity within community and its role in perspective taking?

Metaphor is how we use the traces of memory left by our senses as we’ve encountered the world to make sense of something abstract. That is why metaphor is such a powerful tool for making meaning — to understand the abstractions that are words. Metaphor is, at once, context and connection. The things we’ve seen, heard, tasted, and felt before become references for the things we can only share by thinking about them and imagination is the tool we use to build the bridge. We use metaphor to invite others to be inside our ideas – to see what we see when neither of us can see anything. We use metaphor to stand inside memories with others – to name the patterns we’ve observed — and to check out whether others have noticed them, too.

It is so easy to learn to say things without knowing what we really mean. That’s the “correct answer compromise” that Howard Gardner has written about. As long as children learn to say the right words at the right time — we assume they mean what they say, we tell them they are “right” — and we move on. Gardner writes:

The greatest enemy of understanding is coverage. As long as you are determined to cover everything, you actually ensure that most kids are not going to understand.

Maria Popova echoes this idea:

The only way to glean knowledge is contemplation. And the road to that is time. There’s nothing else. It’s just time. There is no shortcut for the conquest of meaning.

We trade meaning and understanding for the words we’ll need to know on the test and then we wonder why we have such a difficult time getting along with one another. We’re quick to assume that if we’re not communicating well then you must not understand me. But we have little practice identifying the moments when we don’t understand each other, and moving forward with effective strategies for resolution. We are conditioned to believe that words mean the same thing to everyone because there is rarely more than one right answer. “All of the above” often signals that you’re dealing with a trick question, or an exception to the regular format — which is fine until someone comes along who changes the answer key. And no one can argue because no one was paying attention to the meaning in the words to begin with. They were just words we’d learned to believe in — words that were taught to us in specific combinations. But when words meaning nothing, they can mean anything. Suddenly we find ourselves living in a world of “alternative facts” and we don’t have good ways of navigating our way around them. If we had practice with the work of claiming knowledge and not just consuming the answers someone told us we would need, we would be able to perceive connections that lie beneath the surface. We would be able to create new solutions because we’d know that, when it comes to solving problems, we’ve got everything we need. If we weren’t so busy trying to remember what somebody else told us to say, we’d know that it’s possible – and preferable – to write our own lines. That way, if somebody tries to replace the script, you’ll know you can keep writing a story that makes sense. When we have a habit of thinking in metaphor this is easier because we can more readily see where patterns break down.

So I brought the wire out for Opal 4 one morning last week, and I explained: Before I hand this out – I know you are wire experts – I’m going to give it to you to fidget with for a minute – and I’ll tell you why: all the teachers were sitting right here and Lauren… brought us some wire.

Stella: Thank you, Lauren!

Susan: And she asked us to play with it, just like I’m going to ask you to play with it – but as I played with it, I was thinking, Opal 4 would do some super interesting thinking with this. So I’m curious. Before I hand you a piece I just want to look at it for a minute. This wire hasn’t been used, it’s just kind of been unrolled from the spool.

Stella: It’s like your, it’s (audible in take of breath), oh my gosh! They each have their own identity!

And around the circle now, all kinds of excited connections burst from the children.

Amelia: Yeah!

Chase: They can each be molded into different shapes and crafted…

The work with the metaphor is immediate — even faster than I’d expected.

Ella: It’s going to be like your identity.

Alijah: We should do that.

Beyond the immediate recognition of the metaphor, there is the desire to work with the material to express what they are learning about themselves. Students can be so eager to do exactly what you want them to do. Especially when they believe it was their idea. And perhaps it was. Because, like a game of catch — as long as you can keep it going — you soon forget who tossed the ball first. It makes no difference. And, really, it would ruin the game if you stopped to argue over it.

So I passed out one piece of wire, about 18″, to each child. And, without hesitation, they began to talk:

Stella: What you’re doing with the wire right now is changing your identity.

Susan: What can the wire do that can help us think more about this concept of identity ?

Azaleigha: What you don’t really realize is that you’re making your identity every time you do something because that becomes a part of you so when you’re constructing things with the wire, you’re kind of making new parts of your identity.

Chase: You can shape the wire into anything. You can make a flower out of it, but you can also make a dagger.

KD: And then that shape becomes part of your identity. It doesn’t have to be one certain thing. Sometimes there can be multiple answers to one piece of wire.

Orianna: It depends on what you feel.

Chase: Well, when you change it, there’s still more of a twist in the wire so it’s not completely straight anymore. You can still see traces. If it’s a flower, you can still see traces of the —

Casey: dagger.

Susan: The history lives in there.

Lucius: Yeah, you can’t erase all of your identity.

KD: It’s like the onion metaphor that Nate came up with. You can peel off the lumpy parts. Like you could reshape it. But otherwise, you can’t undo the entire thing. Or you’re trying to become someone else.

As in any community or shared culture, the children readily make use of prior meanings they constructed together to help build new ones on. This is the kind of contemplation that knowledge building requires. This is how we practice writing our own stories — ones that make sense. But it is also how we learn to recognize that that is what people do. People create communities and people negotiate meaning within those communities. We learn to live with the ambiguity that comes with knowing that we don’t own the right answer. We’ve just created one possible narrative. We can assume that others are doing the same. And since this is fun — since it is so satisfying to explore ideas and relationships — when we meet others who see the world through a very different lens — we can be curious instead of scared. We can dig below the surface of our conflict and find the patterns that connect us — that make us human.

Thomas: The way it bends is kind of like what you’re doing. You can imagine if it’s bending that you’re going into your danger zone or to your comfort zone. It’s always going to be different after you bend it. (Thomas continues to play with his wire as he talks.) So this is different from that – that’s (pointing to a new crease in his wire) always going to be part of it because you can still see the creases from that.

Susan: It responds to your experience? Or it creates it?

Thomas: (Continuing to twist his wire and reference various new creases and bends) If this is the experience, that experience is still going to live with it.

Almost right away, the wire itself helps move the children towards a depth of understanding that feels new to me. I know this because the development of the ideas is authentically new to me, too. I haven’t thought these thoughts before. I don’t have the answers. What I do have is more experience, a more mature brain, more schema for patterns and connections, more knowledge, and (most of the time) more impulse control. I have learned to assume that children mean more than they are able to say. Early in their literacy development, their abilities to say what they mean with the abstract symbols that are words are immature. But this is the work of literacy learning. The best practice is in actively working to negotiate meaning together.

Alijah picks up on what Thomas has said and tries to make sense of it.

Alijah: Everybody’s bends are different and everybody’s lengths are different. If you try to make it like somebody else, it’s not really your wire anymore.

KD: Yeah, because I saw Thomas at the beginning making a spiral as well, but then my spiral wouldn’t exist.

Alijah: If you cut it to be the same length as somebody else, it’s not really your wire anymore.

Susan: I think you are trying to say something I don’t quite understand yet.

I have learned that in the practice of digging under the surface of things, we often pull up treasures that need a little dusting off before they shine in the light. When understandings get fuzzy, it is often a signal that we’ve found something new. The wire helped Thomas hold the indelibility of experience in his hand, and this is a new idea for all of them. Being able to imagine layers of experience is one thing but contemplating the impact of experience on individuals is another. No longer is it simply cumulative — it is transformative. We don’t just add on. We change. With the wire in our hands, and these questions in our minds, we can see and feel and understand the concept in a way that we never could have by relying on words alone. The materials help us say what we already know, and discover more new connections than we ever could have predicted. My job as facilitator and “more knowledgeable other”, is to know the terrain, to keep us from walking in circles or from falling into a hole, but otherwise to engage in the adventure and not act as a tour-guide who has already walked the path a thousand times and who already knows everything there is to see. There is always more to see. And the fresh vision children have makes them the most qualified to help us do that — if we let them. This is a process of collaborative, dialogic, conceptual map-making.

Ruby: You can change your identity if you change the wire but you can’t change your identity the whole way …

Lucius: You can change it but you can’t erase it.

Ruby: … but you can change it most of the way.

Lucius: You can make major changes.

Alijah: I think we’re talking about personality. I feel like it’s more your personality. It’s harder to change your identity than your personality.

The newly discovered treasure is dusted off and starts to shine new light through the room. I want to make sure everyone pauses to take a look, so I ask another question.

Susan: Which do you have more control over?

Alijah: You have a little more control over your personality, I think. Like you can make major changes to your personality, but — like I said, to match somebody else’s — but it’s not really going to be your identity.

Nate: Your identity is like everything. But your personality…

KD: Personality comes out of it.

Nate: Your personality is kind of like the current most foremost part of your identity.

Alijah: Your identity is what’s inside of you and your personality is what comes out.

New theory sends the group digging for new metaphor — looking for connections, patterns, points of reference that cultivate the meaning, enrich the understanding, and deepen the relationship.

Calvin: I agree with personality because really identity – a lot of times your identity doesn’t change as much like with wire. Identity is more like molding clay kind of. It’s like molding clay that hardens super fast. So like you mold it and it’s already there. You can put something over it…

Roan: (disagrees with Calvin) The wire, you can see a ripple in there now – but clay, you can totally smash it.

Calvin: I’m saying like molding clay, you can put something over it.

Nate: I think clay is more like personality.

Alijah: (realizing what Calvin is saying about the hardening properties of clay) Wait. Clay can be your identity.

Calvin: And then you could paint it.

But I want to make sure we don’t get stuck at a dead end. I want to keep pursuing the journey we are on — not start a new one yet. So I try to synthesize what I’m hearing — to generalize the observations they are making about both clay and wire.

Susan: I’m hearing you say that you can make these major changes with your personality, but there’s still something in there that isn’t —

Alijah: It’s not going to come out. Like you know when you accidentally get that little loop — it’s really difficult to get that out — when you get a knot in the wire it’s really hard to undo. It’s imprinting something into your personality or your identity. You can’t get it out.

Calvin: Wire can really affect clay.

Roan: Wire can make the clay stronger.

They are thinking in metaphor, making sense of very abstract concepts by attaching to them pieces of the world that they’ve actually held in their hands. Our conceptual map is developing more landmarks. They are constructing these new meanings, and that’s how I know they understand them. I don’t need to do this for them. I just need to keep offering them interesting things to play with — which is the best way I know to think about provocation.

Angelina: But here’s the really cool thing. Every single little bump is completely different. So everybody’s wire, in the end, is going to look really different.

KD: When you unroll it, there gets to be these twists and turns at the end.

Ella: When you do this and pull it… (she is narrating what is going on with her wire).

Alijah: I think you can turn it into when you craft something specific, it’s like you – there’s going to be some knots when you craft something. Sometimes you have a fit because there are knots and you can’t get them out. Sometimes you just have to live with it and…

Roan: Sometimes you accidentally make something but then you like it.

Alijah: You can live with it and turn it into something beautiful, or you can just stay in your mindset and say oh this is bad, I can’t fix this.

Liam: You can have a growth mindset.

Liam has offered his own provocation to the group. So I support it.

Susan: Is wire about growth or fixed mindsets, or neither?

Alijah: It’s both.

Liam: I think it’s both.

KD: It gives you a fixed mindset when you realize you’ve got all these bumps in it but then it’s trying to get you to use your growth mindset.

Calvin: I think it’s more about personality – because outside forces can affect it and really your identity – it’s hard for outside forces to affect it. Like I’m trying to use my feet to straighten it – and it gets hot and then it bends.

Chase: With the slightest change, with the smallest experience you can change it. Like right now it’s a dagger but I could just (she makes a little change in her wire) – now it’s a Christmas tree ornament.

Ella: Or a fish!

Alijah: Calvin gave me an idea — about different — you can have — like he was using a strategy to straighten his wire with his feet. Like there are different strategies to straighten it.

KD: But it doesn’t get out the little bumps.

Alijah: It stays the same. Your identity is almost impossible to change.

Calvin: I think your identity is more the past and your personality is the now.

Here is a new dimension to the theory — a new landmark on the conceptual map — and so I help them pause to think some more by asking another question.

Susan: Do you think that identity is all entirely under your control?

Many around the circle answer tentatively…yes… no…

Alijah: Some of it. Well like you can’t change your race, or your story or your family history.

Nate: You can’t control your identity because your identity is your experiences. It’s kind of like your choices —

I am aware here that Nate might take us in a circle — not letting Alijah’s statement move us forward towards a new landmark. He has returned to a status quo, of sorts, but Alijah has offered us new terrain to explore. So I push back.

Susan: But it’s not just experiences — Alijah just added other things — your race…

Angelina: Where your family came from.

Alijah: Where you are born.

Susan: You can’t control those things.

KD: No, you can’t change where you were born, or when.

Susan: You can’t change how old you are.

I realize that we’ve just set up another provocation that the wire might help with.

Susan: Can the wire change to not be wire anymore?

And because they like to argue, they argue for a bit over this. So I try again. I place my own piece of wire on the floor, point to it, and ask a more direct question.

Susan: Can the wire make itself not be wire?

Lucius: Not by itself.

Susan: Right.

I feel confident now that I can push a little harder. And I do want to keep them tethered to basic facts during a dialogue that is not intended to veer into the realm of what is generally established at this point in our collective history to be magic. We could go there some other day — but not today. Because today we are using the wire to construct an understanding of the concept of identity.

Susan: So any influence I put on the wire is going to make the wire change. But it needs influences to change, right? So what does that have to do … are there some parts of it that just cannot be changed?

This course correction has an enormous influence. It’s as if the floodgates come open. I’ll let you read through to the end of the dialogue without interruption.

Alijah: If you neglect your identity, you won’t be able to add stuff and make your personality more of what you want it to be. You can choose part of your personality but not all of it. If you neglect your identity, you be able to add on and then that goes out to your personality, and you can’t change your personality to be what you want it to be. It may just go on and transition into what everybody else wants it to be. If you put your hands on it and mold it to be what you want it to be, there might be some knots, but you might be able to fix it. You’re going to stay you. Your experience, and your family history and your story. You can’t go back.

Lucius: But you can go back – you can…

Stella: You can look at pictures.

Lucius: You can change what you think, so that’s kind of like going back in time.

KD: If you get hurt, then that happened in the past. You change it by — if you were the person that hurt someone, you can change it by saying sorry.

Stella: Or giving them an ice pack.

Calvin: But there’s still your memory there.

KD: Yes, so it doesn’t change it completely, but…

Angelina: It changes how they feel.

Alijah: Okay– but what if you get poked by the wire? While you’re crafting and changing? Like when I was little, I poked myself with the wire. I used to be scared to use wire. But then I tried again and I was like, oh I can fix — I can be more careful and I can bend the end so I don’t hurt myself as much. I develop strategies to help me be what I want to be and be safe.

Lilly: Personality and identity are both you, but identity you can’t really change like it includes other people in it. Because my identity is that I have my mom and dad. They’re part of my identity. But they’re not really part of my personality. I mean, they might impact it, but I’m the one who gets to decide what it’s like. With my identity, it’s more like, there are some things you can change, but there are things you can’t change. But that’s also true about your personality.

Stella: There are some that are fixed.

Calvin: There’s still a remnant of your personality, like a little wave – I was really angry – I used to get angry all the time and that was part of my personality and I can’t change that – well, that was so there might be a few bumps there, but I can change – I was being mean and I got angry and I threw something at him, and I can change my personality to be nicer. There’s a remnant. You can change it super quickly.

Alijah: You can change your personality. Like I used to draw all the time. That was the way I got away from things. I thought I was going to be an artist when I grew up. But then I got exposed to more things and I didn’t just stay in the past. I still love to draw but I don’t draw as much as I used to.

Susan: I bet all of you can think of something like that.

Stella: So, like, some people look at this as like maybe a bracelet or something like that, or an ocean or a sun in the water, but I see it as myself, maybe.So that’s another way of your identity because sometimes you know – like you’re used to seeing these things – like I’m used to seeing this as a person… like the hair …

Roan: Like I know Stella likes to draw those people like that.

Susan: And what you know about somebody leads you to read them in a certain way. Doesn’t that go back to the whole bully issue you often bring up? If I know somebody to be a bully, then I’m going to read what they do as meanness? Even though maybe they didn’t mean it to be that way?

Alijah: You just saw one thing. Like you thought they were beating up somebody and they were actually pretend punching.

Lucius: When you’re perceived as a bully by someone else, they see you as a bully, but that doesn’t mean you are one. That doesn’t mean that’s you. It means that’s just what someone perceives you to be. That doesn’t mean that you’re a bully.

The wire is still in our hands, so I use it.

Susan: Yeah, so if I make this wire into something and you read it differently than something I did…

Lucius: I can read that as a half piece of toast.

Alijah: It looks like a c –

Lilly: It’s backwards–

I turn it around.

Susan: Now it’s forwards…

Thomas: Oh yeah…

Susan: It depends on your perspective, right?

Calvin: For the wire or the empty space? It’s like half-empty or half-full. Are you an optimist, or a pessimist?

Susan: Wow – who knew we could find so much interesting stuff in one little piece of wire, huh?

Lucius: Imagine what 20 pieces could do.

Alijah: What about two?

Calvin surprises himself by snapping his wire in half —

Calvin: Well, I can’t change that part!

KD: I think we’re talking about “persadentity”.

There are so many points to note in this flood of ideas. As the dialogue takes on this life of its own, mostly I listen, and marvel at their thought process and their curiosity and their depth of engagement and focus. But I also am taking notes. I’m audiotaping the conversation and I’m paying attention for the points on this conceptual map that they mark. We’ll want to return to them. Here is some of what I hear that I’ll want to return to later.

- The relationship between personality and identity

- How reflection supports you to change what you think

- There are aspects of our identity that we can’t change, and basic human rights are associated with those aspects

- Our identity influences our perspective and our perspective influences how we perceive the world

- What someone perceives you to be doesn’t make you who you are

- There are many strategies for dealing with the knots and tangles we experience and those knots and tangles are normal

- There are things you can change about yourself and your perspective

- You can choose how you look at the world

I’ll want to return to these particular places on the conceptual map we’re creating because these support my curricular intentions. This is what I want children to learn.

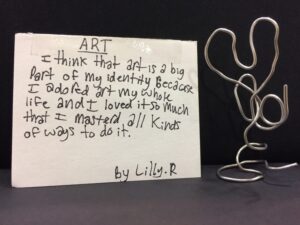

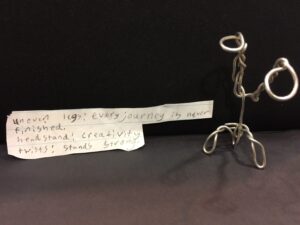

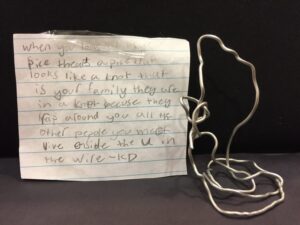

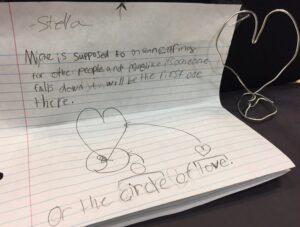

We went on that morning to use the piece of wire we had to create an image that could stand on its own that represented something we really value about our own identity. Here are a few:

I encourage you to use the forum to share some of your own annotated dialogue. What important big concepts are being discussed in your own settings? What are you learning from them that you didn’t already know? How are they helping you assess the understanding of your students? Where will you go next?

So if I may get to the end by going back to the beginning, the road to meaning and understanding and knowledge is time. We don’t need to cover everything. We just need to build strategies and habits by practice that doesn’t teach children to forget to pay attention to their own experiences. As the children noted, right up front:

Stella: What you’re doing with the wire right now is changing your identity.

Azaleigha: What you don’t really realize is that you’re making your identity every time you do something because that becomes a part of you so when you’re constructing things with the wire, you’re kind of making new parts of your identity.

Chase: You can shape the wire into anything. You can make a flower out of it, but you can also make a dagger.

KD: And then that shape becomes part of your identity. It doesn’t have to be one certain thing. Sometimes there can be multiple answers to one piece of wire.

Orianna: It depends on what you feel.

These children understand that your identity is yours to use, that the way you feel determines the choices you might make, that there are always multiple answers, that your choices impact the way you see yourself over time — and the wire helped them say what they mean. They already knew these things, in their own way. They owned the meanings. We took the time and offered the material that supported them to take a step on their journey of literacy learning towards a more sophisticated capability to show what they know and, in so doing, know more about what they know. The wire reflected back to them who they are and who they know themselves to be. What they did with the wire changed their identity.

What materials are we putting in children’s hands? What are they learning to see of themselves?

They are practicing what to do next time someone tells them, “I mean what I say.” Be skeptical. Ask questions. Listen. Dig under the surface and find new patterns that work for everyone.

Susan, do you know the autobiography The Statue Within, by Francios Jacob? If not – you should check it out. He was a geneticist and plays around with many of the ideas in this post through the lens of both his life and scientific work. I’d highly recommend it. – Blake

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/172837.The_Statue_Within

“And since this is fun — since it is so satisfying to explore ideas and relationships — when we meet others who see the world through a very different lens — we can be curious instead of scared. We can dig below the surface of our conflict and find the patterns that connect us — that make us human.”

These words among so many others in your post need to be said and heard and explored again and again. Time, materials, reflection; time, materials, reflection in ever increasing spiral as we continue in our endless journey (if we let it) of approaching meaning making with curiosity instead of fear. Thank you.