Learning to Walk and Talk (and Write)

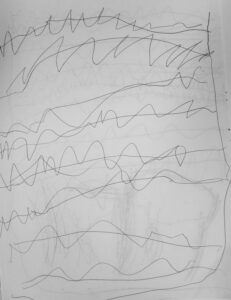

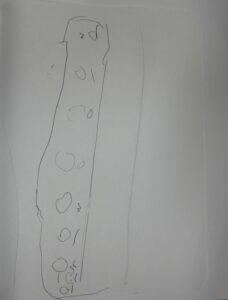

When I first began as an assistant teacher long ago, I attended a parent meeting at the school on the topic of young children and writing. I remember someone sharing that their 4 year old child didn’t write but scribbled. The teacher shared that scribbling (and other mark-making) IS writing — a necessary stepping stone along the path to learning to form individual letters, strings of letters, and, eventually, words. It’s similar to a baby who sits up and crawls before they learn to stand upright, cruise, and eventually walk independently – or a baby who communicates through coos and babbles long before they learn to talk in words. My thinking about young children and writing shifted that day. I had not yet considered writing as a process of developmental stages that each child progresses through in their own way and on their own timeline, much like babies learning to walk or talk. I wondered about a baby’s process of learning to walk and talk and the conditions that support a child’s eventual success to independent walking and talking. I wondered if these same conditions might also support a child’s path to learning to write and communicate through writing.

This story was from early in my teaching career, yet I continue to consider and reflect on the ideas presented that day and have uncovered some conditions that I have found over the years to be vital in supporting children as writers.

When I think about supporting my own children to learn to walk and talk, I made sure that they had ample opportunities to experiment with freely moving their bodies and making sounds, allowing them to take risks and test their limits. I encouraged and celebrated their efforts toward and approximations of walking and talking, meeting them where they were developmentally and inviting them to crawl just a bit further or babble back to me another time. I considered how to keep them safe as they moved about, and didn’t ever consider that the way they moved or cooed was wrong or that it wasn’t walking or talking. I understood that these were important opportunities for learning, the stepping stones to walking and talking.

These same conditions support children as writers. Making sure that they have generous opportunities to make marks, scribble, form real or invented letters alone or strung together, copy words, names and more, offering children the practice that they need to grow their writing. Offering them a safe environment where adult feedback is both encouraging and respectful of the child’s efforts and innovations while modeling writing is imperative. Having adults who are paying attention to where each child is developmentally and gently nudging them along the developmental writing continuum supports children to grow as writers and respects their approximations and the meaning their writing holds for them.

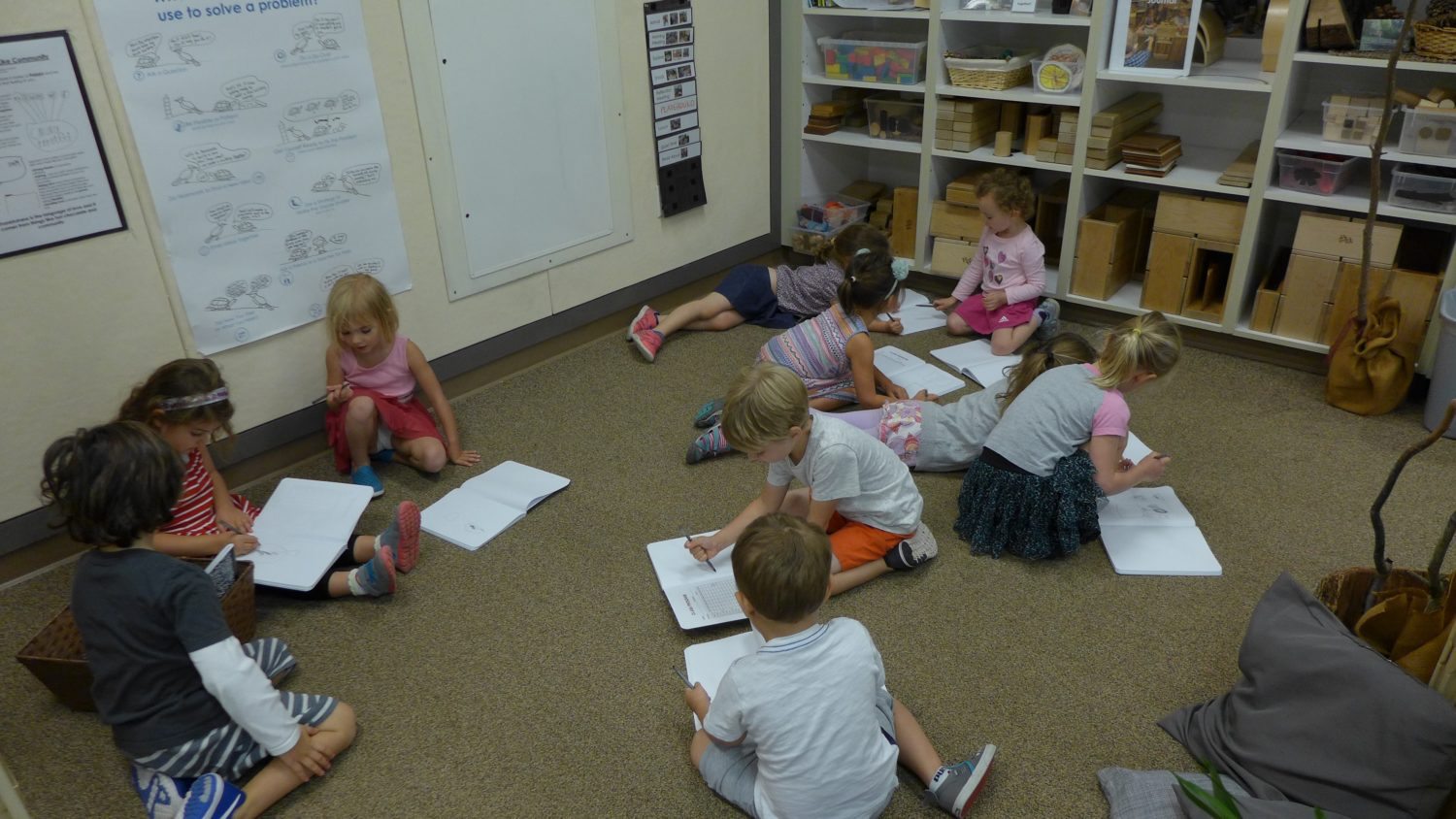

Several years ago, my colleagues and I noticed that children began to use paper and pen on clipboards, mirroring the documenting that the teachers were doing of the children. This sparked an idea for the teachers to give each child their own journal, as each teacher has a journal to capture the children’s stories, thinking, connections, and questions.

Several years ago, my colleagues and I noticed that children began to use paper and pen on clipboards, mirroring the documenting that the teachers were doing of the children. This sparked an idea for the teachers to give each child their own journal, as each teacher has a journal to capture the children’s stories, thinking, connections, and questions.

We see journals as a place for children to regularly practice mark-making and communicating graphically. They can be another tool that young children use to communicate their ideas and understandings of the world — capturing their thoughts, ideas, feelings, and more.

Thank you, Caroline for this post! There is a story I always like to tell to parents of young children. When Teo started preschool at Opal, last year, he did not have much interest in letters or writing but he has always liked to draw a lot. Then when with the whole Cedar Class they started “writing” stories, you had him tell you about the story he drew and then you asked him if he would like to write it out. He told you he does not know how to wrote and you showed him that writing can look many different ways…scribbles, strung letters, spelled words etc. Something shifted in him because for the next few months he filed pages and pages of letters and really started to see himself as someone who can write. We played by trying to figure out what animal, fruit or veggie a letter reminds us of… He found it amusing and kept asking over and over until he figured out most of his letters. Nowadays he likes to “spell” words that I have to sound out and read… endless giggles!

I have noticed that young kids will scribble in their journals or papers and move on to the next page and then the next. I remember pointing out on different occasions to different children who declared themselves “out of paper” that some of their pages of scribbles had lots more space on them. Their response was that they are done with those pages and cannot write on them anymore. This has made me wonder how kids view the surface they write on and the balance between the white of the paper and writing; it also made me wonder what stories might be associated with any random scribbles and how different sizes, textures, or colors of paper or other materials might speak to a different part in children and awake different connections that enable writing and reading.

Thank you Caroline for this post. To this day I keep a large stack of scribbles that my daughter created one day at my sister’s home at age 3 while quietly working her way through an entire stack of copy paper as my sister was preparing dinner in the other room. She was amazed at how my daughter managed to convert approximately 40 blank sheets into scribbles in a matter of minutes. The energy in the marks is bold and vibrant. I often think of how it must have felt for her in that moment of discovery, and appreciate that my sister gently guided her to a supply for that purpose, and shared that she learned to keep her own supply out of reach. I have always loved the Japanese magnadoodle “oekaki gakko” (makes marks and allows for play with negative space mark making as well) You can see an image here on the Japanese Toys R us Website http://www.toysrus.co.jp/i/4/6/2/462471800ALL.jpg

It truly is an exciting challenge to create conditions for safe, playful, and meaningful discovery and exploration of mark making–especially given that every writer is unique and will arrive at their relationship with mark making in their own way.