Finding a Community to Turn To: Community-building, Revision, and Feedback

In the beginning of October, the Willow community embarked on a field trip. We headed to the Bybee-Howell Preserve on Sauvie Island, a beautiful refuge complete with wetlands, meadows, an orchard, and more. Our intention was to spend the day together engaged in various community building activities. As we have mixed age classrooms at Opal, our 4th graders and 5th graders had not been together recently, and we wondered how a day of challenges and play in nature might help build connections between students and set a foundation for us as a community.

We played lots of games with elements of partner, small group, and whole class team challenges. We went on an unconventional scavenger hunt in which each student hunted for qualities beginning with a different letter. Then, they worked together to unscramble the letters in order to spell out the words water, connection, interdependence, wonder, and joy. Finally, we asked them to work in small groups to create a skit that used all five words and showed how they wanted to be together as a community.

Perhaps the dual challenge was too much to handle in the outdoor space at the end of our day together. As students created and performed their skits, we noticed that the presentations tended to focus more on the inclusion of the words found in the scavenger hunt than on embodying the essence of community. Not only that, but one skit really seemed to represent the opposite of what we hoped the students might believe or value about community. In this skit, there was no collaboration, critical thinking or room for growth – characters’ identities were fixed; most were “bad” (dumb, always late, and clueless) and only one was “good” (the teacher’s pet).

In the moment, we let them enjoy presenting and watching the skits. We boarded the bus back to school knowing that the day had provided new connections, enjoyment, and plenty to consider together.

Back at school, we reflected on the experience through writing and materials. Here we saw that what they captured in words and images contrasted with the idea of the skit.

Because we believed that each child in the group didn’t hold the values represented in the skit, we wanted to challenge them to try again. We also knew that exploring feedback and revision were two of our goals for the year. We wondered if we had been presented with an opportunity to make important discoveries about feedback and revision through revisiting the skits.

We were a little nervous about asking them to re-do their skits. We know that feedback can have the opposite effect of its intention: it might shut down rather than grow or inspire ideas, it might come across as criticism, or simply, there might have been too much time between the field trip and now.

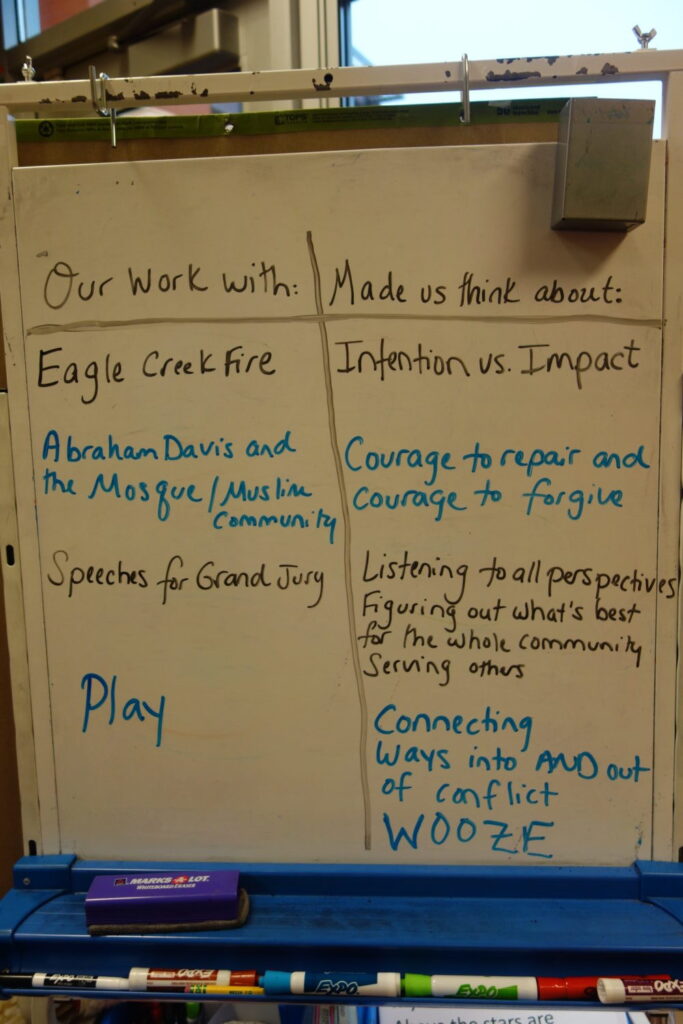

So, we revisited some ideas about community that we had constructed together.

Then, we recognized the strength and value of these ideas and playfully asked the students if their skits really captured or even matched the thinking and experiences we’d had together in the first several weeks of school. They welcomed the idea of having a chance to revise their skits. We intentionally set a time limit for revision and told the students they would perform their amended skits in 20 minutes.

After about 20 minutes, it was clear that two groups were close to ready with revised skits and one wasn’t. This happens so often in a classroom and leaves me filled with uncertainty – how can I support all the groups in getting what they need? What does extending the time do for the groups who are ready? Does more time actually help? Part of the reason why the third group wasn’t ready was because they could not agree on who was taking what role in their skit. With the students cast as they were, the skit just wasn’t getting off the ground, but nobody wanted to give up their part. They knew it wasn’t going well, but they didn’t know what to do about it. With some reservation, I decided to stick to our intention of not giving too much time and to have all the groups perform what they had.

The first two groups went. For feedback, we asked the audience to guess what message they were trying to impart. When the audience’s messages matched, actors knew they were being successful. When they didn’t, that got ideas for how to make their intentions more clear. Finally, it was time for the third group to go. We explained that they knew they weren’t ready and that they were feeling vulnerable and nervous because they weren’t ready, but they were going to try anyway and see what happened. They bravely shared what they had so far. The skit was clearly not finished and the message was hard to tease out – it seemed that perhaps they were trying to offer what they thought about community through highlighting what it should not be. Knowing that they were nervous, the audience gently offered what they saw and offered a few questions and comments that might help them adjust their script.

Then, we gave all the groups another short amount of time to revise again, in order to respond to feedback and the experience of performing. The third group started out by struggling. However, a shift started to take place. The students began playing with the idea of trying out different parts. When one student became willing to give up her role, suddenly lots of new doors opened. There was a productive sense of “what if”: what if I say this? What if you add this? The group began to let go of their individual wants and needs in order to be successful as a group. Their message about community became stronger and stronger as they made adjustments and revisions. Additionally, their responses to each other had shifted from mostly rejecting ideas to accepting and adding on to ideas. They finalized their skit just as the final time for working ended.

We invited this group to perform again. This time, when we asked the audience about the message, they had even more to offer than the playwrights themselves had come up with. The performers were so proud, not just because their skit had been well-received, but because they had figured out so many puzzles – they had the experience of making personal sacrifices for the benefit of the whole group, they had taken the risk of being vulnerable, and seeking feedback before they felt ready, and they had collaborated to implement the feedback in order to develop their work into a more powerful, cohesive piece. They positively beamed with joy and pride. Rather than being individually joyful, they were happy because everyone else was happy and they had made that happen.

We are not sure exactly what happened that enabled this group to make such significant shifts. However, we do know that this story became a touchstone experience for us to return to again and again. Recalling how a group was able to turn to the community with vulnerability and to be supported in revising their work is something we will do again and again – as an invitation, as a reminder, as a boost of encouragement. This experience was a stepping stone in seeing feedback as an opportunity, rather than a threat or judgment or indication of failure.

When we planned our community building day, we didn’t know what would come out of it – but we expected something would. For 2 of the groups, their product (the skits) was about community, but for the third group, their product was really the process they went through – the process of being vulnerable, seeking help, being willing to adjust and revise, to collaborate, and to find that you gain more when you have a community to turn to when you need help and a community you can turn to to celebrate your growth.

This takeaway mirrored the whole experience. Our community building day was less about finding the letters in the scavenger hunt or putting on a skit and more about creating experiences to refer back to and in developing relationships, strategies, and shared experiences. We don’t do activities just to do them, to check them off a list of what “should happen” in fourth and fifth grade. Rather, we try to build experiences that carry enough meaning to move all of us forward.

We wonder – what experiences with feedback have you had in your learning communities? What has been helpful? What hasn’t? How can we create conditions that help us view feedback as an opportunity?

Hannah- I so appreciate hearing the evolution of this exercise, and your honesty about your hesitations, questions, and concerns about the process. How you handled the exercise from start to finish is an example of the very lessons you are trying to teach — intention, courage to repair, and listening to all perspectives.

The more I read the news, the more I am convinced that there is no more important work being done in the world than that which is happening in Opal’s classrooms and being shared through the Center for Learning. Thank you to all the Opal staff for committing yourselves to the desire for a world with more compassion in it!