The Power of Story Part 1

“When we say ‘old friend’, what we really mean is, I know your story and you know mine.”

~Ralph Fletcher, Writing instructor/Author

In January we hosted a curriculum night for Beginning School parents on the topic, The Power of Story. We enjoyed meeting with many who were able to attend, and hope in this post to both revisit and reach out to those who were not able to make it by touching on some of what was shared. Although we won't try to re-create the whole evening for everyone, we will pull out some key points, with examples that were shared to illustrate the points.

Why Story?

“My child is singing, it’s not something he’s ever done; that’s another avenue for literacy. We had a long car trip to California and he’s been making up songs…”

"Over the break my child said ‘let’s find all the letters of the alphabet in our livingroom. It was really tough and I gave up, but my relatives were really impressed he was leading the game and it was all about discovery…”

“I have a question: Should there be a difference between sharing stories from reality and those from the imagination?"

Meaning Making

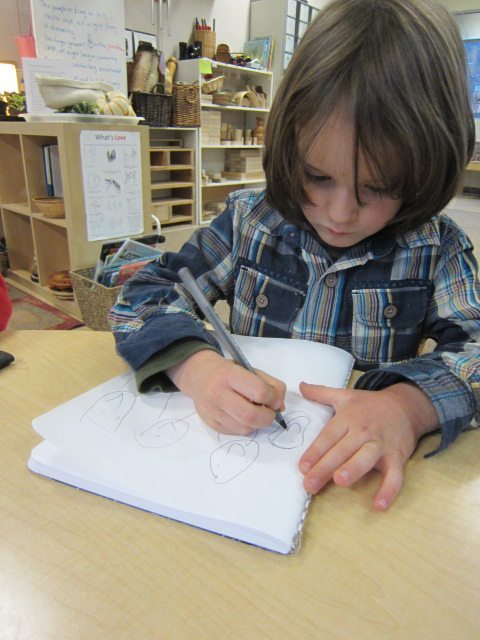

An example of this idea happened for a Beginning School student over winter break who was bit by a dog, resulting in four stitches in her foot. On the way home from the hospital she asked that her family “not talk about it ever again”. When she returned to school – in the safe setting of her community – she showed her stitches to a friend and shared a sneak peek at morning meeting about her experience. The following week, her teachers offered bandaids as a material in story workshop to invite and provoke storytelling, as they knew this held the power to invite children's voice; develop empathy for and grow new perspectives to consider.

After hearing a few stories from her peers, she drew the following picture and explained:

How fortunate for this child that she is in a learning community that recognizes the power of story to begin to understand and make meaning of her experience–her questions, her fears, her sense of well-being. She continues to use story as a way to revisit and heal from this encounter as she shares in a recent Staircase Land story: I went to Staircase Land…there are two guards at the door. They have a guard dog that LOVES children. He really loves children and is nice to ALL of them. He’s a Dalmatian dog. The guards protect Staircase Land from Bears and Wolves.

Connection

Theorist Jerome Bruner proposes that we learn the syntax of our language to tell our stories. This brings us to another idea–that we are wired for connection. "Connection feels like a hole in your heart that has just been filled," states one former Opal 1st grader, and it is through story that we connect with one another and build a sense of belonging. We explored this idea early in the Fall during reader's workshop as we paused on a passage in a book, Will You be My Friend, by Nancy Tafuri.

Theorist Jerome Bruner proposes that we learn the syntax of our language to tell our stories. This brings us to another idea–that we are wired for connection. "Connection feels like a hole in your heart that has just been filled," states one former Opal 1st grader, and it is through story that we connect with one another and build a sense of belonging. We explored this idea early in the Fall during reader's workshop as we paused on a passage in a book, Will You be My Friend, by Nancy Tafuri.

Blue Jay is confronted with the dilemma of remaining in his wet, cold home during a rainstorm, or responding to an invitation from Bunny to join him in his warm, dry home to wait out the storm. Blue Jay does not know Bunny yet, and the children speculated that he would need to muster his courage. This presented a chance for the teacher to invite children to share their connection with this idea of vulnerability by asking, "Was there ever a time when your courage helped you?"

I was scared when I had to swim to my Grandma, but now I can do it! ~ZB

When I walked on the rocks across the water. ~JW

I had to be brave when I walked on the slippery rocks to the deep water. ~QA.

I went to the beach and I was a little bit scared to touch the starfish on the boat, but I did. ~PY

In this way, the children are experiencing the power of story in hearing one another share these vulnerable experiences, and see how each story invites them to add their voice, nurturing a sense of belonging through connection.

How do we define LITERACY at Opal School?

At this point in the evening, we paused to reflect on our definition of literacy at Opal School—which we define as the act of making meaning of ALL that we encounter. This means that if we were to limit our thinking to the idea that literacy begins when children are reading and writing, we would hold the view that preschool age children are illiterate.

Literacy as meaning-making means asking questions, making connections, learning to express in a variety of ways our experiences in the world—through the arts, sciences and through language. We know that preschool-age children already are doing many things that strong readers and writers do. Readers and writers play with language; play with inference, dialogue, and voice; use their imagination; take in information about the world and make detailed observations; use their senses; perceive relationships rich in variety of perspectives and contexts; and so much more! Readers and writers consider their audience and structures of story as they provide context, details, and sequence events. They explore the connection between writing, illustrating and drafting by developing their ideas through drawing and construction to tell and generate ideas for stories. So how do we see our role as parents and teachers in light of these ideas?

When a parent plays with her child; walks together and observes details in the world–patterns, textures, light, tastes, emotions; when we play together with voice and expression; when we sing songs and read books; when we set up areas for drawing and dramatic play, cooking and building–we are nurturing literacy development!

Sneak Peek for Part 2 Power of Story Blog Post:

Schema: The foundation of Story

What role does it play in developing shared understanding and language as well as expanding perspective and empathy?

How does this post stretch your own definition and understanding of literacy development? What connections are you making? Join our dialogue by adding a comment to this post!