The Secrets of Wire: Play, Reflection and Relationships with Risk

As my colleagues and I continued to think together about our big idea of transformation and some of our research questions, we wondered what materials might lend themselves to playing with this big idea. Wire came to mind as a material to explore together: it is easily transformed, offering these young children a concrete experience in seeing the immediate power that they hold to shape and reshape it in their hands, generating endless possibilities. Another one of wire’s secrets is its ability to connect, which we believe is a critical characteristic of playful inquiry and one that the classroom learning community is continually making meaning of together. We know that humans are hard-wired for connection and seek connection with others, with materials and ideas, and the world.

We wondered:

How might wire support and deepen our understandings of the idea of connection, as well as the crucial role that it plays in a learning community?

We have been exploring and paying particular attention to feelings of risk and the idea of taking a chance when confronted with someone or something new, so we wondered:

Would any of the children experience any feelings of risk as they explored a material that was new to them, even one as open ended as wire? What strategies would they use to address any feelings of risk or uncertainty to continue to take on this exploration?

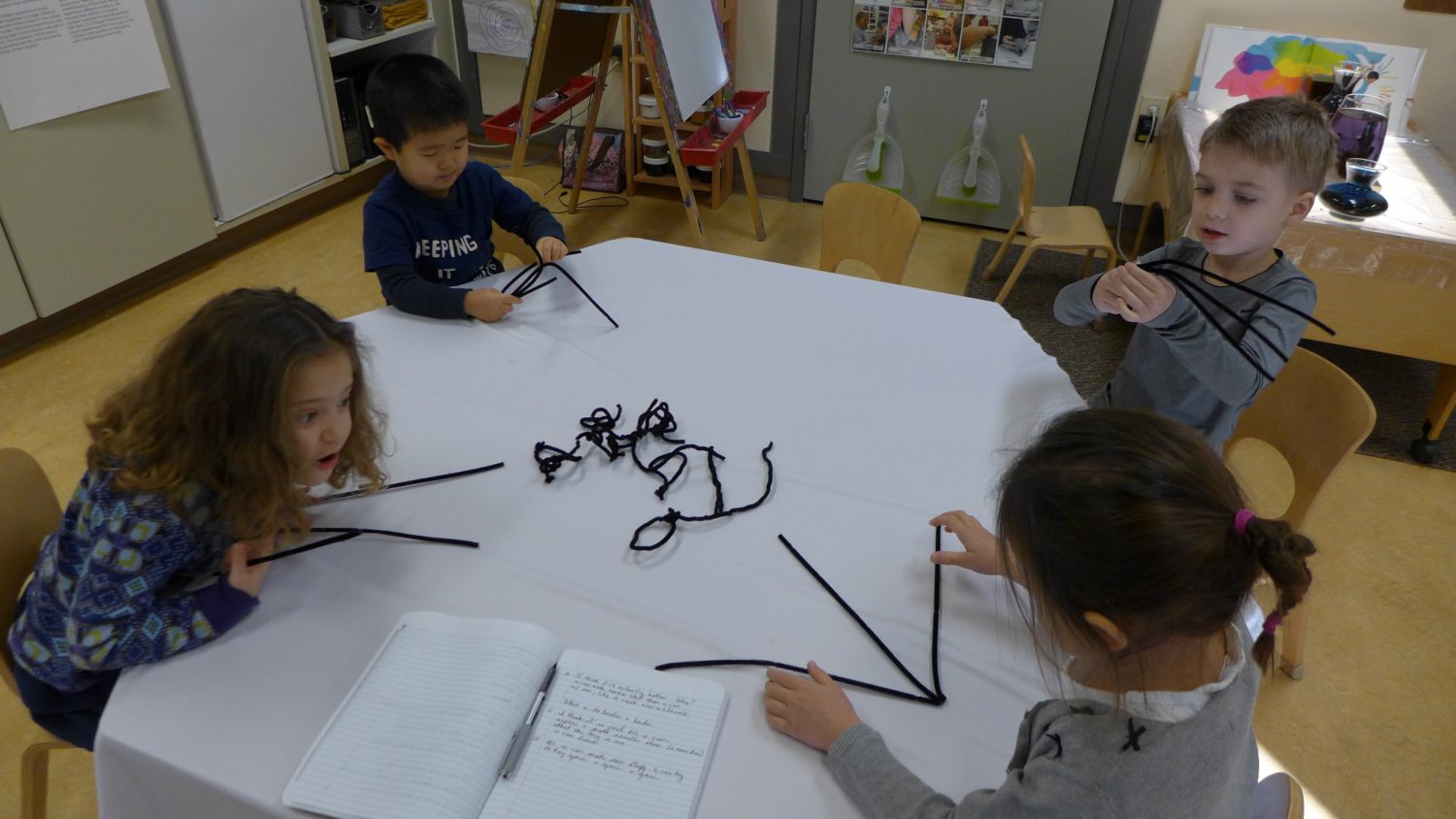

As I sat down with the first small group of preschoolers last week to introduce this new material, I was met with excitement by each of them. I handed them each one pipe cleaner and asked them, “What do you notice about this material and how might you change it?”

Mary: It is a line.

Oriel: It has pokeys on the end. Be careful!

Ethan: it’s soft.

Rob held the pipe cleaner in his hands, placed it in an arc shape on the table while saying, “It’s a rainbow!” And then he let go of both ends, to which he noticed, “It just went BOOM!, back into a line!”

The children continued to explore the many ways that they could transform the wire, innovating strategies to manipulate the wire, offering language to what they were doing and sharing ideas as they shaped and reshaped the wire in their hands.

Here is a short excerpt of dialog that emerged:

Mary: I made a rainbow, too!

Ethan: Corn!

Rob: A lasso! I tangled it (the name he gives his strategy for connecting it to itself).

Oriel: I twisted mine and made a heart.

Ethan: I tied it (showing us the knot in his pipe cleaner).

Rob untangles his and notices that it is no longer completely straight and asks the group, “How do you turn it back into a line?”

Mary: I don’t know.

Rob compacts it in his hands and shares his next idea: “A ball.”

He then uncrumples it and says, “Look! A twisty rainbow!”

Mary: A mountain! When I let go of it, it turned into a cloud!

After a time, I asked them if they would like to keep playing and see what they discover, but this time with two pipe cleaners. They all were eager to continue, so I gave them each two pipe cleaners and invited them to keep sharing what they were noticing and discovering.

They continued to offer the possibilities that they created as they shaped the pipe cleaners, such as, a ladybug, a braid like our hair, a really tall pole, a yoyo, a cross, a lion bee, and a new strategy was invented that was not possible with just one pipe cleaner, a hook.

After a time, I asked them to pause and reflect on what they noticed about one pipe cleaner versus two pipe cleaners. I added that they could also think about what was the same or different about exploring one pipe cleaner or two.

Here is a bit of their initial thinking:

Mary: It is easier with one.

Rob: I think it’s a little bit easy and a little bit hard with two.

Me: Can you tell us more about this?

Rob: With two you can make an ‘A’ or a bunny.

Mary: A butterfly.

In the moment, I was surprised by Mary’s initial proposal of the difference in the number of pipe cleaners being easy, and then Rob building on that idea to consider what is easy or hard. I wanted to consider this new thinking, but decided to wait and offered them the invitation to play with and explore three at a time. At the end of our time together, we reflected on the whole experience and I again invited them to share what they noticed and discovered while exploring one, two, or three pipe cleaners.

Again, their reflections immediately centered on the ease and difficulty of one, two, or three pipe cleaners and what their preferences were.

Mary: You can use it a different way from two. It’s a little easier to make something with three.

Me: Why do you think it is easier with three than with one or two?

Mary: I don’t know. I think it is easier.

Rob: I liked two because sometimes I was trying out things that were a little bit easy and a little bit hard (repeating his earlier idea).

Oriel: I thought one was harder to explore an idea.

Mary: With three you can make a little harder stuff than two or one.

Ethan: Two was hard for me to make an anchor. It came out as a wookie bar anchor instead.

Me: What do you think about doing things that are hard? (I decided to ask this question as I was curious to hear more about their working theories on taking on something that feels hard.)

Oriel: I think it is good because you can explore and make something else about the thing you are doing. You can learn.

Ethan: Because you can make new stuff. You can try again and again and again.

That afternoon I reflected on this experience with my colleagues, and then later I revisited my journal notes and photos. Reflecting on these experiences is an essential strategy that we practice at Opal for making meaning of what we see and hear from the children, the ideas and questions that the children are exploring in the encounter, and where the connections and gaps are for both the children and for us as teacher-researchers. Reflecting on these experiences and questions supports us to consider possibilities for how to move forward next time in the most meaningful and engaging way.

As I reflected, I was reminded of how excited the children seemed as they explored the pipe cleaners. I admired the children’s fluidity in generating multiple possibilities as they played with and manipulated the wire(s), mirroring the flexibility of the material with their flexible thinking. I noticed that they saw one another as resources, as when Rob asked the group how to get his line back, and as they built, borrowed, and connected to one another’s ideas and strategies, such as when Mary was inspired by Rob to make an arc and then see what happens when she lets go, as he had done earlier. I didn’t notice anyone feeling uncertain or hesitant, so I was curious then when I asked them to reflect on their experiences, as a way to dig deeper into their experience and the connections they were making, they seemed to struggle more. I noticed that they used words, such as easy and hard, which I typically associate with taking a risk or the absence of one, or with taking on a challenge or not.

I was so curious about their ideas of preferring something to be easier or liking it when it was more difficult. I wondered if they were using these words in the same way that I was – or were these words a communication shortcut for them to describe their innovative process? What theories are they developing about taking on a challenge? Was I possibly witnessing them playing with the ideas and communicating about a fixed and growth mindset (related to this research by Carol Dweck)? I found my own reflections to mirror the twists, bends and knots that the children discovered in the wire.

This experience underscored the importance for the children in our classrooms to be practicing and developing their empathy and compassion, but also their resilience as critical thinkers, willing to take on challenges and see themselves as innovators of ideas with the ability to communicate and collaborate with others. Basically, we want them to develop and practice using many Habits of Mind. We want our classroom communities to not only be kind and caring, but also places where children’s curiosity muscle grows and connects them to lifelong learning.

Towards the end of the small group’s reflection, Oriel said, “I’m tired!” In that moment I wanted to acknowledge the hard work that they were doing and to frame it and name it for what I thought it was: thinking and growing their brains. I wanted to reflect back to them the idea that something that is hard (or tiring) can also be fun. So I replied with a hint of excitement in my voice, “Do you know why you are feeling tired? I think it is because your brain has been doing a lot of thinking and growing right now!” Upon hearing this, Mary excitedly asked, “Do you mean like when we feel friendship and our hearts grow bigger?” (an idea that we have frequently talked about in class). I said “yes,” and each of them smiled, perhaps considering what they were feeling in a new way, as how it feels when your brain is challenged. As I reflected on this exchange with Oriel, as well as how each of them struggled to find words to express their reflections, I wondered what structures and materials best support children to communicate their thinking and reflections of their experiences. Specifically, we regularly witness the power of materials to support the children to express their thinking – and I wonder how we might incorporate more diverse materials for children to communicate their reflections of their learning.

Going forward, my colleagues and I have more questions to add to our research that will also guide our playful inquiry. We wonder:

What are the children’s experiences thus far with taking on challenges?

What are the children’s working theories about the role of challenge in learning? About the role of risk in learning and transformation?

What language and experiences will support the children to value developing a growth mindset?

What might happen if we support the children to be aware of when they are stuck in a fixed mindset and develop strategies to become unstuck?

What are the children’s current understandings of their sense of agency and empathy? What experiences will deepen their understandings?

What are the children’s experiences outside of the classroom with taking responsible risks and taking on challenges?

I love the opportunity you found in a comment that may have otherwise been brushed away. “I’m tired” can feel really challenging as an educator who put time and effort into creating the experience for the children, and watched as they made discoveries and connections, and then have it end with a child exclaiming what could be viewed as a complaint of the work in front of them. Instead, you saw it as a way to mirror back all the effort that hard work took, and why that child might be feeling that way. I’m so inspired by your ability to listen this way, and articulate your thinking back to the children. Now you’ve got me thinking about thinking!