Say What you Mean

We’ve been infected with this kind of pathological impatience that makes us want to have the knowledge but not do the work of claiming it. I mean, the true material of knowledge is meaning. … And the only way to glean knowledge is contemplation. And the road to that is time. There’s nothing else. It’s just time. There is no shortcut for the conquest of meaning. And ultimately, it is meaning that we seek to give to our lives.

Maria Popova, interview with Krista Tippett

I wonder, sometimes, when we contemplate what school is for, if we forget to ask ourselves first whether we are trying to create environments for making meaning or environments for consuming information (and mistaking it for knowledge). How does information become knowledge? What do we mean when we say meaning? While I believe that we have a long way to go to understand how best to create optimal conditions for meaning making in the classroom, I wonder if it is safe to assume that is everyone’s goal? What is the relationship between meaning and knowledge? Why do we so often take for granted that one is the same as the other? What happens when we assume knowledge without taking the time for the contemplation that it requires? Lewis Carroll explores this terrain in his classic, Alice in Wonderland:

“Then you should say what you mean,” the March Hare went on.

“I do,” Alice hastily replied; “at least–at least I mean what I say–that’s the same thing, you know.”

“Not the same thing a bit!” said the Hatter. “You might just as well say that “I see what I eat” is the same thing as “I eat what I see”!”

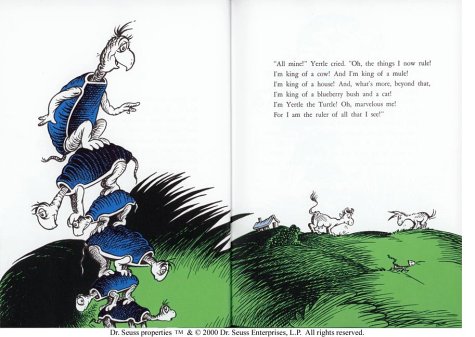

Is Alice’s assertion correct? Is it really “madness” to concern ourselves with the inconvenience of the Hatter’s truth? If our only responsibility is to mean what we say, we don’t need to worry about the impact we have on those around us. We don’t need to be curious about whether we meant what we said by paying attention to the impact we’ve had on others. When someone says to us, “That hurt my feelings,” we have a ready excuse: “That wasn’t my intention.” And we can leave it to those we’ve offended or hurt or threatened to swallow their dissent. We can stand in our certainties and on our stacks of information we believe to be knowledge and say what suits us – all of which conjures another image – this time from Dr. Seuss:

It’s easy to mean what you say because it leaves others to do the work of contemplation for you. We say, “knowledge is power”. Is this what we mean? In our work as educators – as those responsible for the dissemination of knowledge– have we thought this one through? Do we mean that once you’ve stacked up enough turtles (or collected enough “knowledge”) to be the leader of the free world you can say anything you like, because no one need concern themselves with what you mean? That you are no longer responsible for figuring out how to say what you really mean because you can expect others to take your word for it? YOUR word – regardless of the wildly different worlds that might live inside those words for others? Do we mean that as you have more power, my experience with your words matters less and less because you’re not responsible for the impact they have on me? In other words, the more power you have the more right you are and the more wrong I am?

It is far more difficult to say what we mean. It is difficult to be curious about the impact we have on others. It can be painful to discover that the experience others have with what we say isn’t what we meant for it to be. But we often don’t know what we really mean until we see how it works for someone else because, well, it doesn’t mean anything until we do. Meaning is always a transaction. And that’s why Karen Gallas, in her book, Imagination and Literacy, defines literacy as a growing capacity to merge what you show the world with who you think you are. In other words, literacy is the growing development of your ability to say what you mean.

The work of claiming knowledge is the work of engaging in transactions between ourselves and the world and being willing to explore the knots and the breakdowns we encounter within them. For this reason, we can’t support lifelong learning if we can’t support children to be comfortable with vulnerability. And we can’t support children to be comfortable with vulnerability if we are not ourselves. We find out what we mean by trying to say what we think about what we notice, feel, taste, smell and hear. We find out what others and other things mean by seeking connections between what we perceive and what we remember, in an endless and ongoing exploration of the world around us. The road is time. It is filled with the joy that comes from leaning into conflict and resolving it. Whether that conflict is not understanding a concept or a word or being hurt by the actions of a friend – there is joy in the resolution. And counting on that joy, really trusting that it will come, is what keeps us learning. It’s what gives meaning to our lives.

What strategies support children in the classroom to be willfully curious, to feel safe taking risks, and to say what they mean — valuing the many revisions that may require, and, as Ellin Keene has described, learning to be “intoxicated” with the power of their own minds to make new connections?

In my post, Materials as Metaphors, I reflect on the recent experience in Opal 4 that led me down this thinking path. I would love to hear your thoughts and responses.