Reflecting on Leaning In With Curiosity (Part Two)

In my last post, I told the first part of our story of using Playful Inquiry to create conditions for children to lean into making sense of the world with curiosity rather than judgment, to accept and seek out complexity, and to develop empathy and understanding for people and perspectives different from their own through interactive examination of – and reflection on -refugee stories from around the world.

Here is the rest of the story – though it’s still unfolding, of course, as these stories have become inextricably part of us as individuals and as a community and they continue to influence our interactions and experiences.

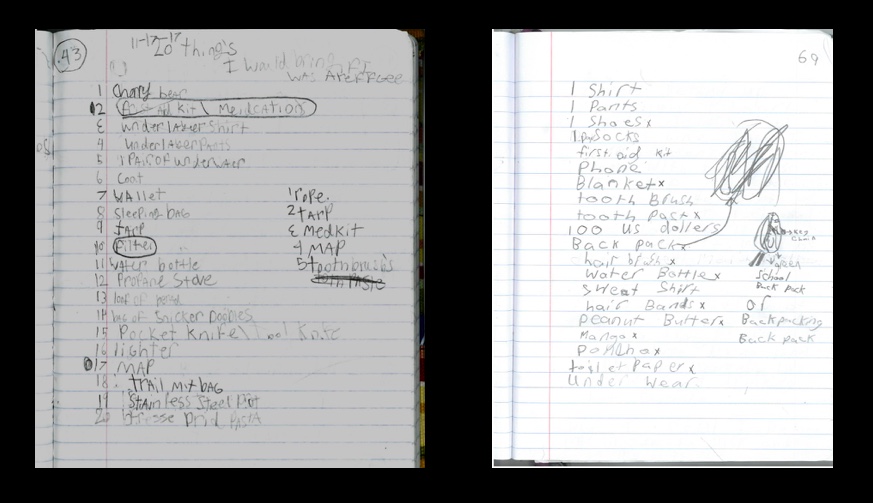

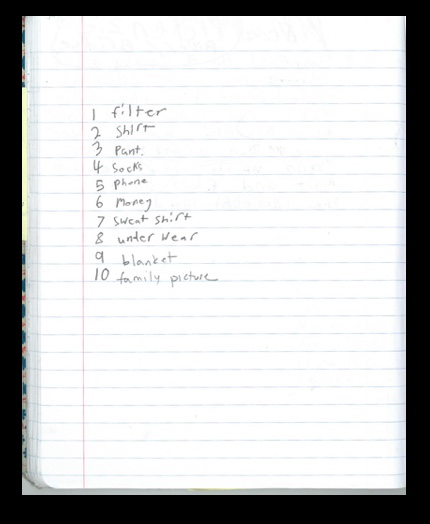

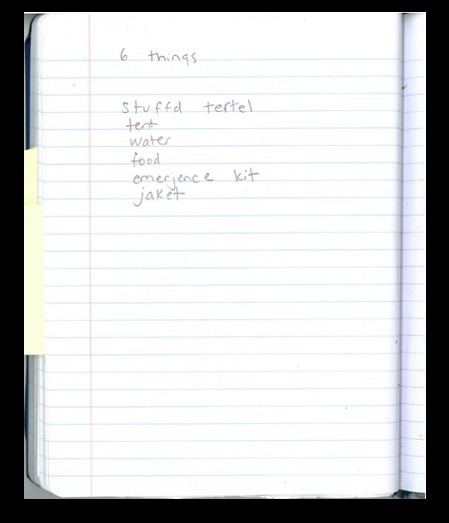

After various experiences with different stories of refugees, we wanted to bring the experience closer to home for the students. As many of the stories we had looked at included details on what refugees carried with them, we asked students to make a list of 20 items that they would bring if they had to leave home suddenly.

Then, we asked them to cut the list in half.

And, of course, we asked to them reflect on what that felt like.

Eleanor: On my list of twenty, I brought things for entertainment and comfort, but this time I could only bring the essential things, like the stuff I really needed or could use, and this time it was difficult because I couldn’t bring any of my comfort items or anything fun.

Daisy: At first I thought about what I wanted to have with me, but as I cut my list I started to think about what I really needed, and then I realized what I needed became what I wanted – that’s what I think would really be most valuable to me.

Leila: It felt hard because there are a lot of things I need and a lot of things that I really wanted. It was hard but I felt like I needed the things I needed more. It was hard to choose because I liked all the things I had on my list.

Then, we asked them to cut their list in half again.

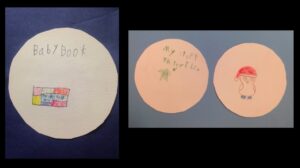

At that time, we looked at another series of pictures – stories of special items that refugees carried to remind them of the people and places they left behind. We asked students to make sure they had a special item on their list, a token of their homeland to bring with them. We had them take a list of 5 items plus their special item and make a token for each of the items they would bring.

Meanwhile, the teachers had been scheming behind the students’ backs. We devised a refugee experience in the arboretum. At Opal, we have often used drama as a language to help us better understand history, perspectives, and cultures. Often, students are brought into the drama through a cold start – there is no introduction, no “this is a roleplay” – it just starts. The day after they finished making their tokens, we interrupted our morning meeting and told them to gather up their items as quickly as possible because we had to leave.

We set out as a class. We had been told there was someone waiting at a safe house to guide us. Once we arrived, she told us she could only lead half the group to safety. She said she would return for the other half. After waiting for what seemed like too long, the group decided she wasn’t coming back and set out on their own.

Both groups moved through the arboretum in their quest, facing trials and tribulations along the way. They had to give up or use up many if not all of the items they had so carefully selected: they lost some in a river crossing, they ate their food, used their first aid supplies, traded valuables, and more. When their boat crashed, the group that had been left at the first safehouse was split again, and only then did they realize that most of their life jackets did not work. The boat captain left with 3 students, leaving the rest behind to try to make their way.

Finally, everyone made it safely to our destination and we reflected on the experience.

Oceana: I felt like I understood what it was like but that gave me even more questions.

Leo: The hike made me more aware of all the dangers. When we got to the safe place we had to experience a lot of different feelings and not all of them were good. It was like devastating. Not fair. Some people had 2 or 3 things. I worked just as hard. What made me deserve to lose my things?

Daisy: Well, it seemed like everything was fine. And then a few of us started to get really worried that we wouldn’t get the chance to get to Canada and that we also wouldn’t have a chance to met back up with everyone else… but then we kept getting separated… I felt worried and scared.

David: It was interesting how some people didn’t have anything and still got to a safe place. Other people would help them when they ran out. Other people would pay for them. That really struck me, like what other people would give up.

Afterwards, we had them reflect with materials and write in order to capture what they took away from the experience.

I was particularly struck by Cooper and Louisa’s responses:

Cooper: It made me feel more like I knew more about how it felt when refugees were fleeing, but at the same time – we didn’t go through the whole experience – we don’t know all of it – but we know more.

Louisa: Same as Cooper – it felt hard and stressful to not be able to know what would happen next, were you going to get hurt or killed or fall over and hurt yourself or break your leg – it was fun but I could feel – I could not feel as much as the refugees could feel.

This conversation reassured a different worry I had. In planning our refugee experiences, I had concerns about the presumption or potential insensitivity of what we were doing – who we were to pretend that we were refugees? – and what Cooper and Louisa captured was so important to me. They realized that our dramatization did not compare to a real experience, but somehow being aware of that heightened their understanding of what it might be like. By recognizing that there was so much that they still did not know, they were able to have more empathy and curiosity.

In each of the experiences we crafted, we sought to heighten emotion in order to heighten thinking. We continuously wondered if it was working: Would having these experiences that gave a sense of emotional involvement make a difference in not only their understanding but also their thinking dispositions and capacity for action? Would caring about their experience in the arboretum make them care more about refugees? Would that in turn, extend to caring about someone or something else?

We hoped the relationship between thinking, feeling, and caring would enrich our ability to understand, connect, empathize, and act. Neuroscientist and former teacher, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, tells us that emotion is where learning begins. When there is emotional involvement, you can see evidence of engagement on a brain scan, which shows activations all around the cortex and down into the brain stem. You don’t need a brain scan to see when students are engaged, curious, and invested in what they are learning – you can see it on their faces, in their questions, and their persistence to understand more. Immordino-Yang says that meaningful learning happens when students are able to create an emotional connection to what might otherwise remain abstract concepts, ideas, or skills. And yet, far too often, students in school view what they are learning as irrelevant and unimportant to their lives, which makes it harder to learn. How can we study what matters to students and make what we study matter to students?

Susan says that if we want to teach students to think, we have to allow them to feel. This is another version of what Immordino-Yang is saying. It seems to me that the more we are able to care about something, the more we can think about it, and the more we think about it, the more we find the capacity to care.

At the same time, it’s important to separate what we are studying from the dispositions we want to grow. We chose to study refugee experiences for a variety of intentional and carefully considered reasons. However, in the end, my hope is that our work is not just about developing care for refugees. I hoped that using Playful Inquiry to develop an emotional connection would help us grow as critical thinkers and compassionate citizens – that having developed an emotional connection to this one issue would lay pathways in our brains and bodies in a way that would help us develop an emotional connection to other issues so that we could then explore and understand them more thoroughly and thoughtfully, and with more curiosity and less certainty.

We have had many meaningful experiences that have pushed all of us and yet, I am left with many questions.

- Will students generalize their experience beyond having empathy and responsibility for refugees in particular to other groups in need? Will they see themselves as agents of change?

- Will they apply what they have learned about figuring out how to care about what seems irrelevant or scary or foreign to other situations?

- Will they recognize and live with complexity rather than trying to simplify, to reduce the matter into right and wrong, good and bad, or other limiting categories?

These questions guide us as teachers, inspiring what stories we choose and how we go about exploring them, and helping us know what to look for. We are curious to see if students will apply and draw on these habits as they encounter novel situations in which they decide to they will lean in with curiosity and care or lean away with alienation and fear, or perhaps catch themselves leaning away and make a shift. We hope the experiences they have in getting this practice through playful inquiry not only help them to lean in to care but also to figure out that they care and why they care and what happens when they do.

Anne Vilen writes, “making change begins with empathy steeped in deeper learning,” but I think 11-year-old Oceana says it better:

These situations are really different than ours so it might take a lot longer to step in, but once we can step in, we understand a little more… then, we can use that empathy as a tool.