Reflecting on Leaning In With Curiosity (Part One)

In the beginning of the year, Opal School teachers wrote letters of intention. As Matt wrote here, these letters are our North Star – our guide as we navigate our way through big questions, relationships, curricular content and more in conjunction with our mission, guiding principles and values, and goals. They are a source to return to again and again throughout the year as we reflect on the intentions we laid out in late summer.

Recently, teachers spent an evening sharing the stories and experiences that have unfolded since we wrote those letters of intentions. In the Willow community of fourth- and fifth-graders, we shared stories of how we used playful inquiry to guide us through an in-depth study of refugee experiences. I wanted to share that story here. Because it is quite long, I’ll tell it over two posts.

We started by highlighting two parts from our intentions letter:

This year, the Opal School Intermediate Team is particularly curious about relationships between play, the arts, empathy, and invention. Our work is intended to grow a new citizenry that has strong emotional intelligence, a real discomfort with certainty, and a deep sense of empathy and civic responsibility. How will children gain experience in seeing how their ways of thinking can increase justice and well-being? How will we connect the work in our classroom to the world outside?

In light of our goals and expectations, guiding principles, and values, we wonder: How can we explore interdependencies and stories of the past in a way which inspires us to take action as mindful citizens?

This year, we have been wondering how we can create conditions for children to lean into making sense of the world with curiosity rather than judgment, to accept complexity rather than resorting to categorical simplifications, and to develop empathy and understanding for people and perspectives different from their own. In this question, we see a deep connection to caring and have been wondering together, students and teachers, what it means to care and what it takes to care for something bigger than and different from yourself.

We thought that the current refugee crisis would allow us to investigate these questions and goals. Given its complexity and the vastly differing experiences and perspectives as well as its role in American politics today, it made sense to explore the roots and consequences and experiences of these forced migrations. We hoped learning more about this issue might inspire us to be moved by what we see in a way that calls us to action.

We also thought playful inquiry would help us with work. We hoped that playful inquiry would allow us to develop an emotional connection to the stories we would examine as well as a sense of belonging and connection with these stories of people and experiences that are so very different from our own.

And so, we began.

We read and discussed books and articles that allowed us to begin to think and wonder and empathize with refugee experiences. These included Margriet Ruurs’ Stepping Stones, Alexis Deacon’s Beegu, and Refugee by Alan Gratz, which captures the experiences of 3 different refugees in 3 different time periods.

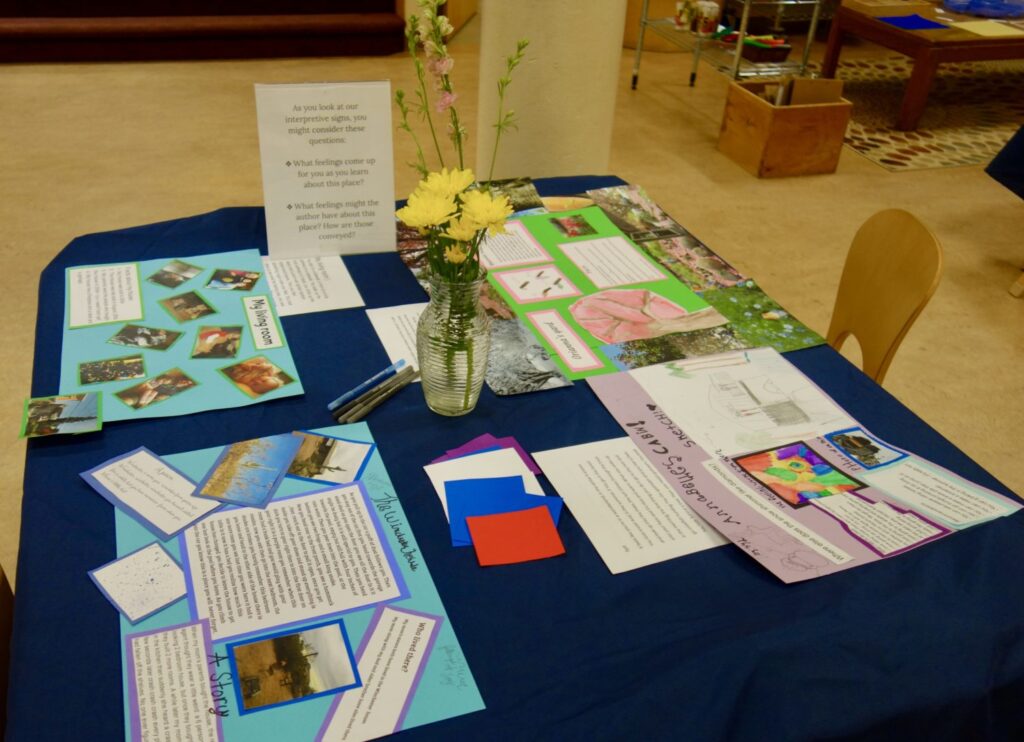

We started a genre study on interpretive signs to develop and express a sense of connection to special places. We thought understanding connection to place might help us better understand what it means to leave a place.

Our foret into thinking about refugees through playful inquiry reminded me of the tremendous and enormous uncertainty I feel when navigating new territory. I had lots of hopes and wonderings and worries as we entered this terrain. I hoped that the experiences of playful inquiry we were offering were helping to create habits of being curious, asking questions, recognizing their own and others’ perspectives and taking responsible action. At the same time, I wondered what sense these children could make of something so vastly different from their own experience. I worried they would be culturally insensitive, and how I might respond if and when they were; I worried their emotional responses might be overwhelming and I wouldn’t know how to navigate supporting them with their feelings in a way that led them to a place of greater understanding and empathy. And, sure enough, all of these hopes and worries came to life as we moved forward.

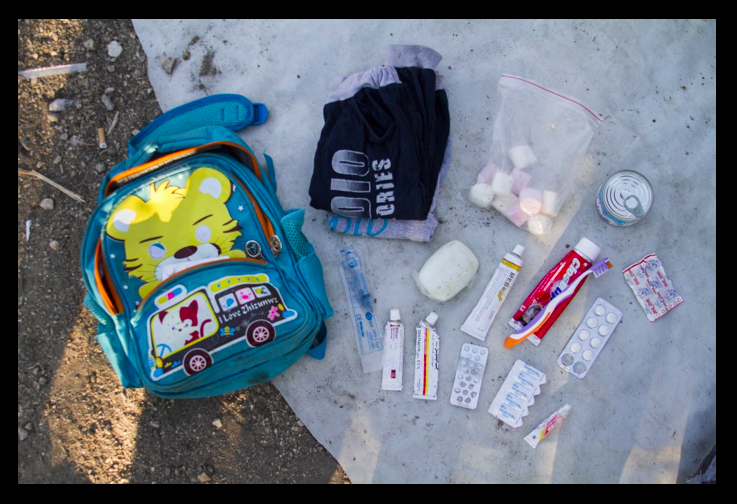

For example, when we examined the International Rescue Committee’s series “What’s In My Bag?” which portrays images of what refugees bring when they flee for their lives, we saw shifts in students’ thinking when they leaned in to make meaning as well as assumptions and judgments.

Students worked in pairs to study the images and read stories of the people behind these heartbreaking collections. Afterwards, I asked the students to reflect through a thinking routine called, “I used to think but now I think,” which is a powerful tool for students and teachers for realizing and recognizing shifts in thinking. Through this routine, I was struck not only by the students’ deeper understanding of experiences so foreign from their own, but also their awareness of their own growth of understanding:

Oceanna: I used to think that being a refugee was hard, but it really didn’t go into my brain about how hard. The story I looked at was about a mom who had to carry her baby through her whole trip. Her whole bag was packed for things for her baby and none for her. it made me realize how hard it was for them.

I wonder how often we hear stories that we recognize as hard or awful without letting them go into our brains, without allowing ourselves to be emotionally connected. It happens all the time: listening to the news; reading a history textbook; hearing the experience of a distant person. This reminds me of the need for us to develop an emotional connection to the story in order to connect with and better understand the situation.

This same series of pictures brought out other reactions too. The class at first was very critical of a family’s decision to bring marshmallows for 6 year old Omran.

This critical judgment, this presumption that they knew better what to bring alarmed me. Even more, I worried about how quickly they jumped to these conclusions without slowing down to ask questions, consider the situation, or get more information. I was unsure of what to do, so I asked them to pause and I started to ask questions.

Wait a minute – I hear you asking why did they bring marshmallows, but it doesn’t sound like you are asking a question. It sounds like a judgment. Let’s take it as a serious question – why would they bring marshmallows?

There was a pause.

Maya: Maybe they helped him accept the journey.

Magnolia: He is leaving everything he knows, maybe this familiar snack will bring him comfort.

Hannah: Do you always get up and go when someone asks you to?

Class: Noooo!

Hannah: Let’s think about what we’ve heard about some of the journeys…they are mostly on foot, walking long distances in uncomfortable situations. What if they have to run suddenly and they are so tired – do you think a marshmallow might help a 6 year old do that?

Seeing the power of story and images in our experience with the What’s in My Bag series motivated us to bring another set of stories to the children. Brandon Stanton, the creator of the Humans of New York series, put together stories of Syrian refugees, which told heartwrenching details of their journeys. (slide) Pairs of students each considered one of the stories–stories of children, families, or individuals making their way out of Syria.

Knowing that the reflection time is when they could make sense of what they were figuring out, we asked them not just to engage in thinking deeply about the stories and pictures, but also to reflect on that experience.

Isaiah– well it is crazy that such a tiny bit about them could bring out such strong emotions.

Charles– I realized it was probably really hard to take care of your kids because you are feeling really scared…

Eleanor – I didn’t fully understand what happened in my story which made me realize that they probably did not understand either…so much happened to them and it was so hard for them to keep doing all the things they needed to do, like be parents and figure out their new life.

I asked – What do you think you’re aware of now that you weren’t before? Another version of I used to think but now I think.

Louisa– The stories let me be able to feel their pain and be able to step in to their shoes, and not to just see a photo and say sure those people have had some trouble… but to be able to read their story and see how hard it is, to try to feel what they felt. It was hard, but it made me want to read other stories at the same time.

Oceanna– This woke up my awareness about how much danger these people feel, even when they make it to their place they still don’t feel safe… so even when they get to their place they feel super unsafe and in their danger zone

Maylin– I realized that even if you get to a place that is safe that doesn’t mean that you feel safe

We also asked what might compel people to help others. They had lots of ideas about how having a similar experience can build empathy for others. However, what I wanted to know was how do we build empathy when we haven’t had the same experience as someone else, so I asked again: what would it take for someone who hasn’t had this experience to care?

Cooper: I think hearing the stories makes it different…not just hearing the stories, but thinking about them, feeling them – that could make someone want to care and to want to care they have to understand.

At this point, we were starting to see shifts in the students’ thinking, particularly in terms of their empathy and understanding for refugee experiences. We were still curious, however, about the impact our work was having on their ability to draw from these experiences to have empathy for other people in other situations, whether right here in Portland or farther away. We were also wondering how else we might develop an emotional connection to our work.

I’ll tell what followed in the next post, but for now I’m wondering:

What experiences are unfolding in your classrooms that help children lean into complicated stories with care and curiosity?

What intentions did you set at the beginning of the year? How are your reflections on those intentions guiding you during the last few months of school?

Very interesting post Hannah, I am so glad the kids got to explore such important and urgent issues and build their empathy for children who are going through unimaginable hardship. The marshmallow conversation was particularly striking. The kids are going to miss your teaching so much!

Thank you, Belinda! It’s all a collaborative effort, both in terms of teachers supporting teachers and students and teachers learning together.