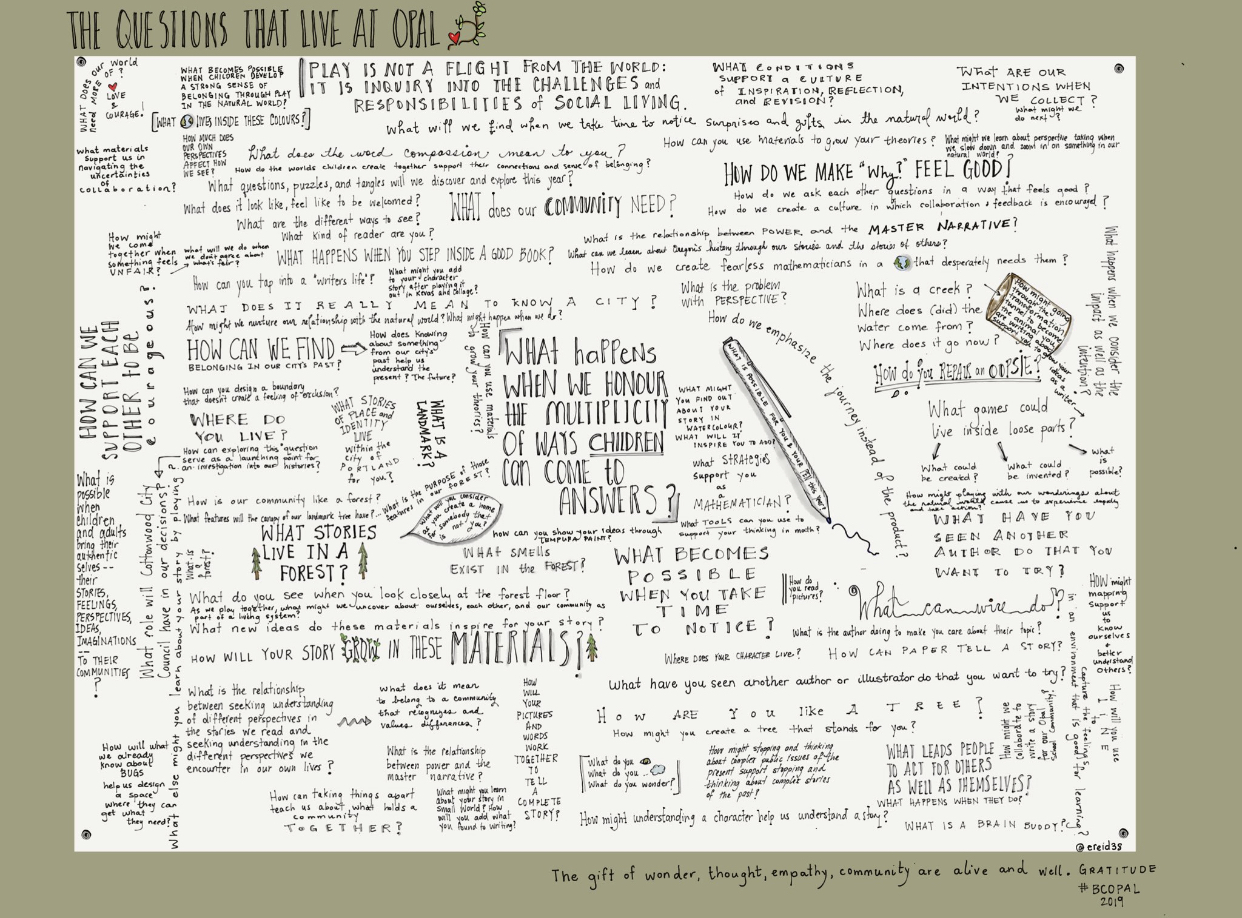

Questions as invitations to play

It’s always a treat to have posts written by guest authors! This one is written by Ben Mardell, Principal Investigator at Project Zero. It is co-posted on the Pedagogy of Play blog. The related sketch-note is by Ellen Reid who found herself paying attention to questions as she participated in this week’s Study Tour of educators from British Columbia.

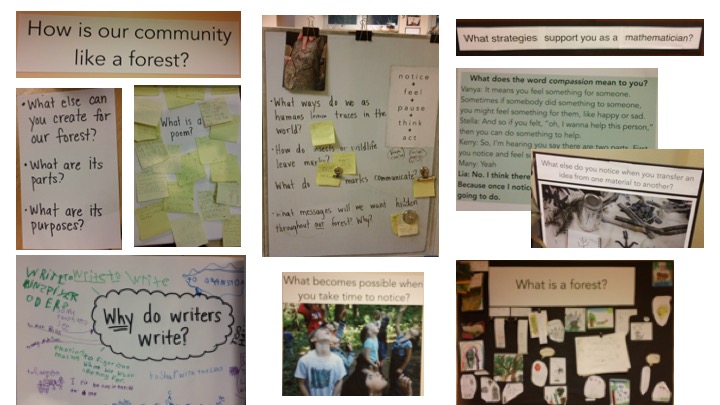

How is our community like a forest?

What does the word compassion mean to you?

What do you notice when you transfer an idea from one material to another?

What strategies support you as a mathematician?

What would it be like to be the size of a lady bug?

In early January I had the pleasure of visiting Opal School in Portland, Oregon. I spent three mornings in the Dogwood classroom where Heather Scerba teaches 21 engaged, energetic, and welcoming six, seven, and eight-year-olds.

One of the first things that strikes you when you enter the Dogwood classroom is the wealth of questions around the room. Some are printed out in big, bold letters and posted on the walls. Some are part of documentation panels that include children’s thoughts about the questions and analysis of this thinking by the teachers. Some are part of working documents where hypotheses and data related to the question are being collected. Some are hand-written on white boards and meant as provocations for the children as they write, draw, and explore with materials like clay and blocks. Some are questions asked by the teachers, and others by the children.

How is our community like a forest? A big, complicated question. And after spending time in Dogwood, it is clear the children are up for questions like these. Indeed, the intellectual life of the classroom revolves around these questions. For example, how is our community like a forest is part of a set of questions that also includes what is a community and what is a forest. The questions are the basis for an ongoing investigation that will last the entire school year.

I love these questions. They call for deep thinking and imagining, and they clearly benefit from collaboration. Questions like how is our community like a forest are open-ended. And not only isn’t there one right answer, as far as I know, no one has answered this question before. The children must invent their own answers. The questions in the Dogwood classroom are invitations to play—to play and be playful with ideas.

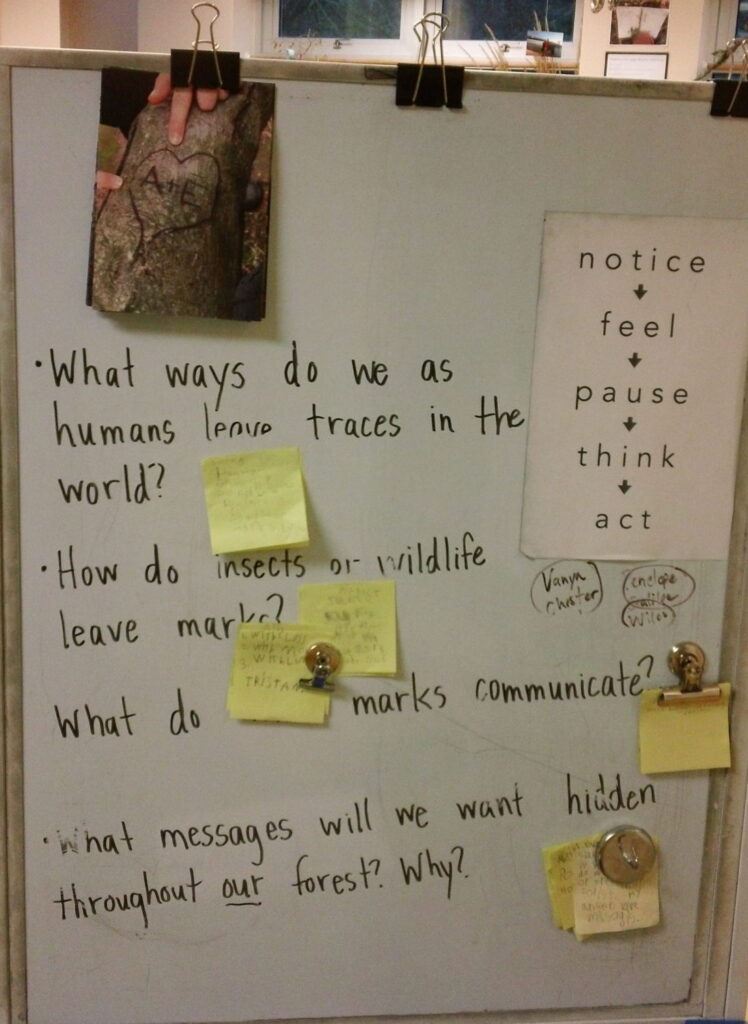

Naturally I was curious where the questions came from, so I asked Heather about the origins of four questions that were on a white board in the meeting area:

What ways do we as humans leave traces in the world?

How do insects or wildlife leave marks?

What do these marks communicate?

What message will we want hidden throughout our forest? Why?

The children encountered these questions for the first time at their Monday morning meeting and began to “crack them open,” to use an Opal term. After discussing the questions they went off and explored them in small groups. The class returned to these questions each morning during my visit, and they guided the children’s explorations into forests and communities during the week.

Heather explained the genesis of the questions and how they are connected to the learning goals of the classroom, have specific children in mind, and are things that she and her colleagues are curious about too. At the outset of the school year Opal teachers write intention letters outlining their learning goals (articulated in the form of questions) for their students. In Dogwood, the teachers wondered how might nurturing our relationship with the natural world support empathy and agency? An investigation grounded in the nearby forest ensued.

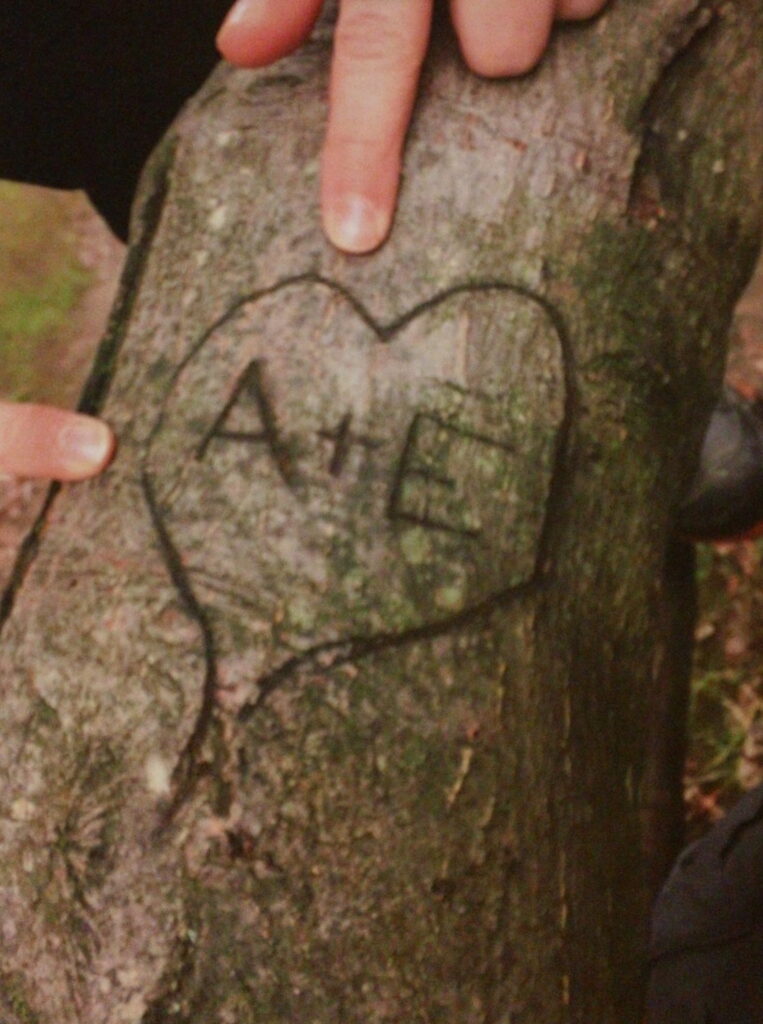

The preceding Thursday, as part of this long-term inquiry, Amy Maki, the PE teacher, had taken the children on a hike into the forest. She emailed Heather her notes and photos about the ideas, interests, and questions that emerged during the hike. A heart with initials carved into a tree was one of the children’s big discoveries.

Heather decided to use this interest, but, as she explained, “I didn’t want them to get stuck on marks and just focus on the carvings. I wanted them to think bigger.” So her first question used the word traces. Her second question, about wildlife, was written with a child who loves animals in mind. In the final question, “hidden” appeared because Heather noticed the children using this word in various conversations and felt it could infuse an element of surprise and playfulness. Heather explained that writing these questions wasn’t a solo endeavor. They emerged in conversations with colleagues.

Of course, not all the questions in Dogwood were written on the wall. Teachers and students were asking questions all the time. The nature of teacher questions, which challenge, guide and motivate students, is worth remarking on as well–but that is the subject of another post.

And, by the way: What would it be like to be the size of a lady bug?