Possibilities Within Our Intentions

At the beginning of the year, our teams of teachers draft intentions for the year. These intentions take the form of big, meaty questions that invite the children to chew on social, political, and historical issues that align with the values and guiding principles of our school. As the learning community becomes immersed in these big questions, we are constantly paying attention to what other doors these big ideas can open that might offer the children opportunities to meaningfully engage in various concepts, skills, and ideas third-graders have a right to investigate.

In the search to dig deeper within the historical, social and political opportunities that Portland history offers us, we brought the children the story of Tanner Creek and were curious about what path their thinking would lead us on. In “What Lies Beneath”: The History of Tanner Creek, the children reveled in the story of a creek that once flowed through their city but now was covered up by neighborhoods, public transportation, restaurants, city streets, and even the beloved soccer stadium, Providence Park. The last sentence of the article stated that even though the creek was covered, it was not gone. It read:

“Most subtly, however, the wooden seats in section 118 dip slightly in the middle as a result of the previously sinking foundations and a reminder of the gulch below.”

How was this possible? How could this happen? What was going on? Through a story about the history of our city, the children were now invited to ponder ideas around scientific concepts such as absorption, erosion, and deterioration in a natural way.

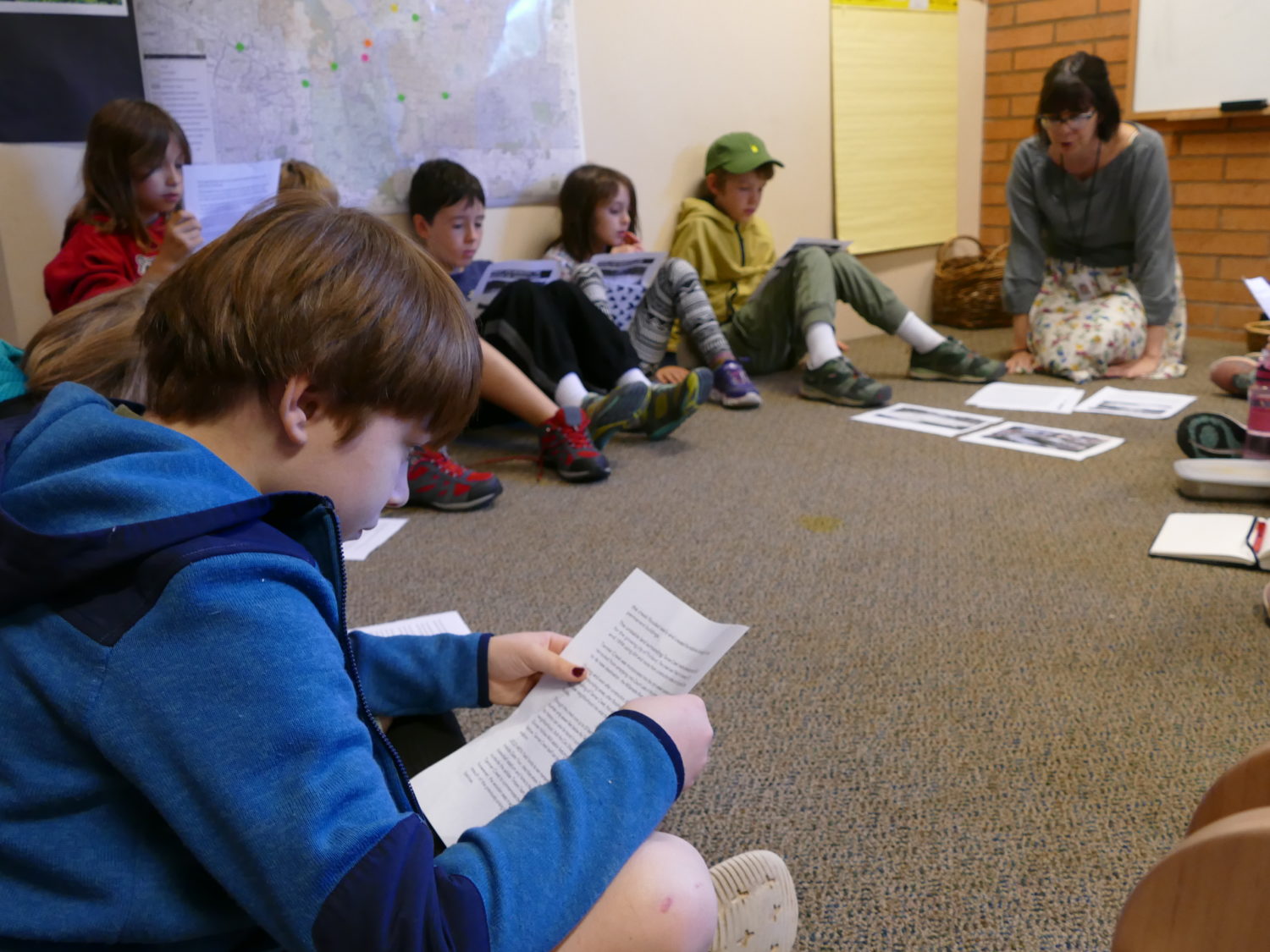

The children shared their theories behind this natural phenomena during a Science Talk, a structure (first described by Karen Gallas) that we use at Opal School to invite children to play with ideas. It is intended to provoke thinking and to build a shared understanding of a scientific question that we think the children might have some theories about.

Kevin: Some of the water got incorporated into the sewer system, most of the dirt turned into mud and got squished on top of that. And the water was still flowing through.

Fred: When they took the water, they put dirt and rocks on it and that made mud and so the rocks sunk into mud. When they put the stadium on the mud, the stadium started to suck up some of the water

Aurora: It’s like a sponge because sponges lift water up. And the mud, maybe the stadium had a little bit of holes in it and maybe and it could’ve sucked up the water a little. Do you know how you dip your hair in the shower it gets heavier? It’s like the stadium getting its hair wet.

Emmy: When they built it there was less water, some of it went into the sewer and some of it got absorbed by the sun and now the water has nowhere to go and it still there and its beginning to sink in one part since the water has nothing to do. It sits there. And slowly it’s making the sand they put in there turn into, sort of like in the sandbox when we put a bunch of water it turns into goop and it’s bringing some of the power down from it and it just stays flat.

Allen: The creek, I think, went up because the rocks absorbed it but then the rocks maybe it pushed down on the mud so the water came out of the mud, so it went dirt, rock, water (showing the layers with his hands).

Fred: I think the dirt and water made mud and like Aurora said it was a sponge so the mud was slowly sucking down the posts that folded up the stadium and 118 was sinking because there’s a post under it.

After sharing, the children then thought together about the possible next steps and how they could uncover some of their wonderings.

Allen: I was thinking we could do more of a scientific way. We could have an experiment. We could put sponges on top of water, and sand on top of that, and see if it sinks.

Through their theories, questions, and possibilities, it seemed as though the children already had an experiment in their mind. With their questions, their current understanding and schema, and their curiosity to learn more, they conducted a first and open experiment. Armed with their question (What makes something sink?), and simple materials like water, sponges, rocks, sand, and pieces of concrete, the children were off to gather information, hypothesize, experiment, and draw conclusions based on the theories of their learning community.

The experiment offered the children the opportunity to tinker with their ideas around this natural phenomenon. They had an idea, and together with their community and the time and space to play and explore, they were able to model their theories to find out new possibilities.

What story is the data that you collected telling you?

Polly: Most things sunk because rocks and gravel are really heavy and sand is too and wax is light…and a sponge is strong…and I was also noticing the difference between a lot and a little.

Alexa: It really matters (a lot and a little)…its just like me…if you put a lot of books on me…I couldn’t hold it….but if you put just 5, I’d be fun. It matters how much you use.

What did this make you wonder about Tanner Creek?

Logan: Maybe there is gravel under the section and it’s making it sink.

Skye: Like the foundation is sinking?

Fred: I think all the dirt in the water make mud and especially on that side of the stadium and it’s slowly sinking.

In our project work, we use many thinking routines that help us uncover ways to make our learning visible – by digging deeper, investigating different perspectives, sharing theories and providing evidence. It is within this investigation that we offered the children another thinking routine in the form of the scientific method. This particular thinking routine gave the children space to tinker, try things out and play with scientific concepts like buoyancy, the power of distribution and the rate in which deterioration naturally occurs. It is also here where we, as teachers, are able to pay attention to the gap between where the children are now in terms of understanding and where we want them to be. It is within this gap that we will continue to build upon their theories, ideas, and wonderings through further exploration and experiments. It is also in this gap where we may discover what we can do, as facilitators, to help the children go further in their learning. Some questions we ask ourselves after this first experiment are:

- What different questions can we ask next time?

- What direction will help the children go beyond the surface in their wonderings?

- What structures can we introduce that may help the children in their own inquiry?

As teachers, we are looking closely at our intentions and searching for all of the connections, skills, ideas, and possibilities that they are made up of. In doing so, we are inviting children to slow down and to hold on to curiosity as they explore, wonder, and play in meaningful ways within everything that makes up their known world. We are hopeful that within these big and complex interpersonal issues there are also big and complex skills and concepts that invite children to connect to and find connections within. As we build upon the layers and complexities of our world with concepts and ideas we can hold on to and chew on together, we are creating ways to support the children to better understand the big ideas that live around them – as well as the world itself.

Reader, what skills, ideas, and concepts live inside the intentions for your learning community?