Play, school, and the future of jobs

As much as I find good reason to treat anything that comes out of Davos with a measured dose of skepticism – and as resistant as I am to describe the function of schools as a workforce delivery mechanism – I find the periodic Future of Jobs Report to be provocative. As the World Economic Forum projects what skills will increase in importance in the workforce and which will decrease, it’s worth considering their implications to the classroom.

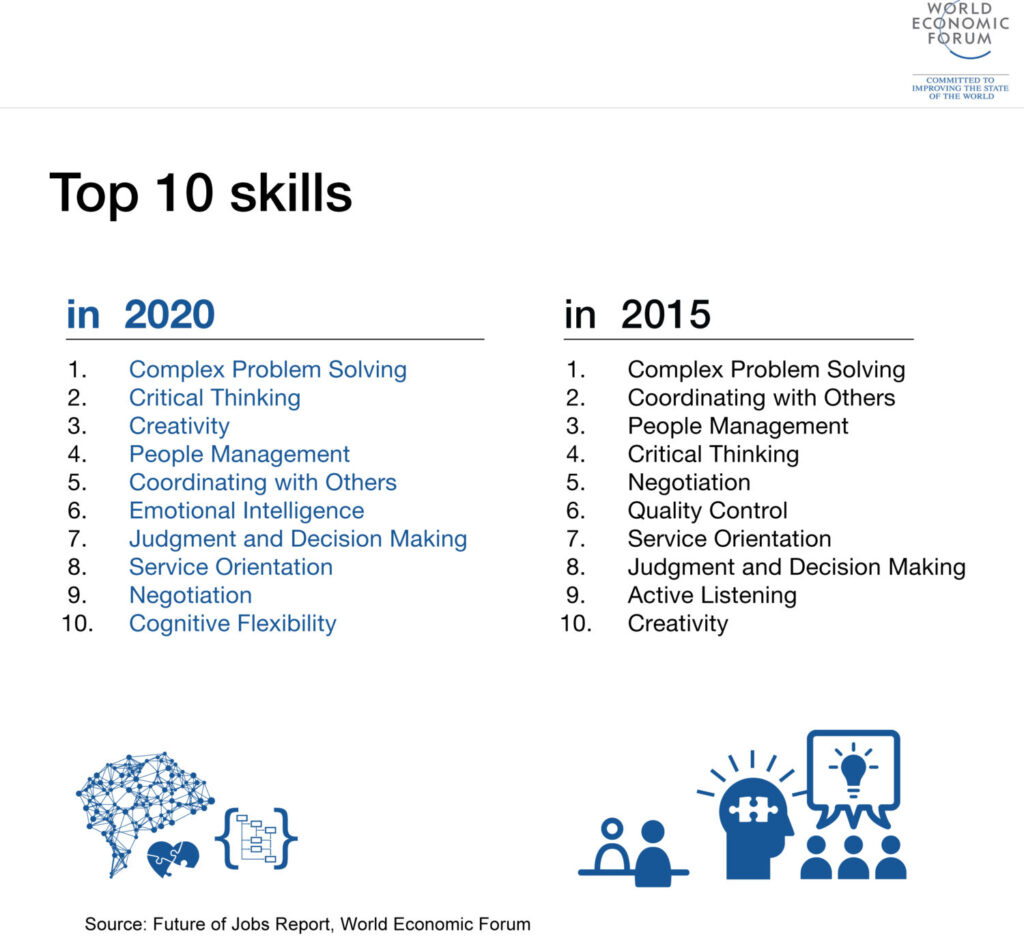

I’ve discussed this table with educators several times over the last three years:

I had my first conversation about the new report last week.

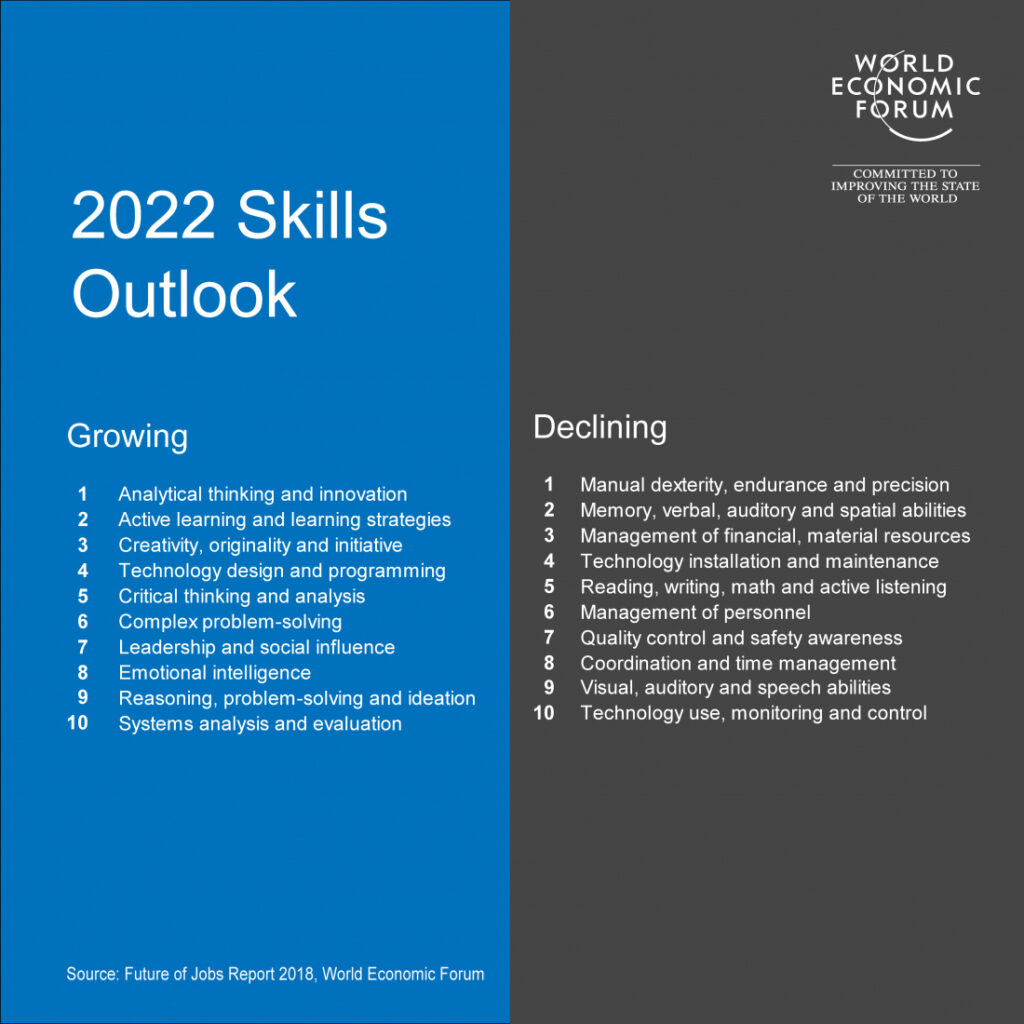

Unsurprisingly, the most vocal teachers I shared the new report with last week reacted to #5 on the Declining list. Almost as much so today as when I was in elementary school in the 1970s, “Reading, writing, math, and active listening” describes the dominant view of the purpose of elementary school across North America. In fact, so much of what was most visible in schools then and continues to be today sits on the Declining side of the table. But the world is different today: the increasing domination of AI issues different demands on both our work lives and our civic responsibilities (more on this in The Atlantic’s Why Technology Favors Tyranny.) I don’t read this list as indicating that there is no longer any call for the development of reading, writing, math, and listening skills – but it does offer yet another challenge to anyone arguing that the development of those skills should be the core purpose of schools for any age child.

I’m curious about the lack of any explicit call for collaboration on the list. Coordinating with Others– #2 in 2015 and #5 in 2020 – has disappeared in 2022. The new addition of Leadership and social influence might be seen as taking its place, but it connotes more manipulation than responsiveness; the authors seem to imagine a lonely work world. That may be where we’re going – and if that’s the case, I think that’s one of those spots where schools offer possibilities for developing capacities beyond our role in the economy.

This week, 85 educators from across North America come to Opal School to think together about how we construct courageous, collaborative learning communities in our schools. I’ll look forward to thinking with them about the unique value of that conversation at this point in time. The threat to our current economic way of life posed by AI that informed this list – and the related increasing threats to democracy – can be seen as offering schools an opportunity to focus our attention on those traits which define our humanness; to invite children’s natural learning strategies and build on the opportunities of being together. Playful Inquiry is so well suited to developing all of those skills on the Growing list. Games, too – but play all the more. And it has the added asset of supporting that ability to develop the courage, collaboration, and learning communities we know we’ll need in any economy.

I’ll finish with some words from the Atlantic article I referenced above –

We need to place a much higher priority on understanding how the human mind works—particularly how our own wisdom and compassion can be cultivated. If we invest too much in AI and too little in developing the human mind, the very sophisticated artificial intelligence of computers might serve only to empower the natural stupidity of humans, and to nurture our worst (but also, perhaps, most powerful) impulses, among them greed and hatred. To avoid such an outcome, for every dollar and every minute we invest in improving AI, we would be wise to invest a dollar and a minute in exploring and developing human consciousness.

Reader, tell me: What’s your response to this document?