Listening for what they need

Hannah published this provocative post earlier this week in a section of the site exclusively available to members. I repost it here for two reasons. Firstly, I think this is important reading for everyone coming to Opal School’s Visitation Days: this post, like Susan’s recent one and so much of what we publish here, reveals how we’re inquiring into playful inquiry these days and prompts you for the presentations, observations, and conversations you’ll be engaged in when you’re here. Secondly, I wanted to give readers who aren’t yet members a sense of what lies behind the curtain, hoping that will be the nudge necessary to buy yourself a holiday gift by signing up now (simultaneously, you’ll be giving a gift to Opal School – a real win/win.) Enjoy!

Children will tell you what they want. If you listen, they might show you what they need. by Hannah Chandler

In my last blog post, I reflected on Opal’s 3’s experience of getting their writer’s notebooks, a process which I hoped would help them see themselves as writers. Pivotal to this experience was our work with two quotations:

A writing life is a life with all the windows and doors open. – Julia Alvarez

Ideas are all around. – Philip C. Stead

While these words did serve their purpose for our work with writing, they became far more instrumental and significant than I could have imagined. In discussing these ideas and through using materials, reflection, and shared experiences, there was a burst of energy and thinking about the meaning not only for writing, but as a lens through which to see the world and how to live a life.

Hannah: What do these words mean to you?

Taylor: Everyone can be a writer who has their doors and windows open and sees ideas in everything!

Ollie: Your doors really need to be open to slow down and think about new things.

Eli: If the doors were closed, you’d be stuck.

Ruby: You can find new ideas if your windows and doors are open.

Ollie: It’s hard to find ideas when your doors and windows are closed.

Eli: Your mind has to realize there are ideas out there – and you have to have your windows and doors open to be able to find them.

Taylor: I have a connection to wonder. I think it’s the same thing. You can’t wonder if your doors and windows are shut. You can’t think or learn.

Suddenly, the students were realizing the need to look outward for ideas, possibilities, and questions as well as the value of being curious, open, and even uncertain. Instead of looking inward to locate and share what they already knew, there was a newfound sense that there is more to find and that not being absolutely sure may lead us to find even more. This exciting shift allowed us to begin exploring ideas together – to enter new and undiscovered terrain without any one expert leading the way.

Although I did not realize it at the time, the two quotations, in conjunction with the work leading up to getting writing notebooks, was an instance of what we refer to at Opal School as a ball toss. A ball toss is a playful way of explaining the idea that curriculum grows as an exchange between children and adults. I “threw” the quotations to the children and listened for and reflected on what came back. When the response showed engagement, energy, and excitement, I knew I could and should do more with these ideas (our friend Erin Moulton explains the ball toss metaphor much more eloquently and clearly in her recent blog post).

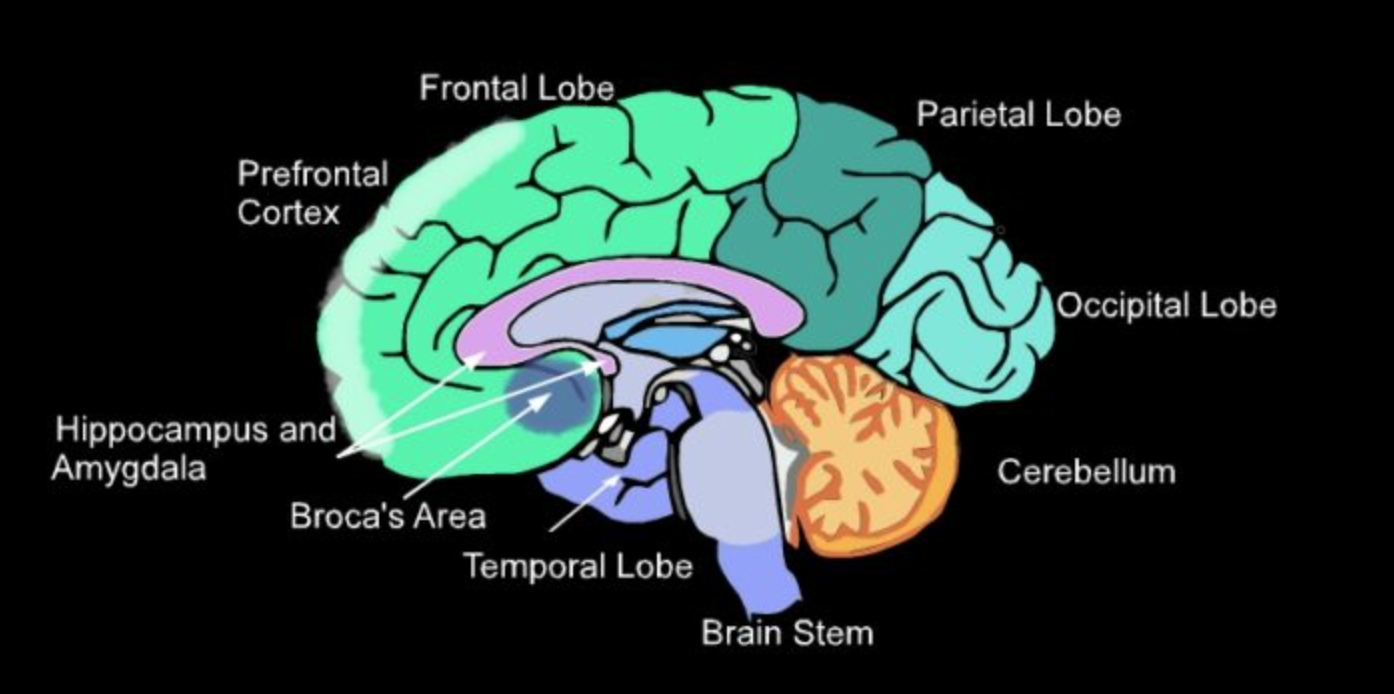

I began gathering ideas, consulting colleagues, and seeking resources to figure out what “ball” to throw back next. I wondered if I could build on their metaphor of being open and closed by offering opportunities to explore some recent discoveries about how our brains work. Knowing that this group of students loves information, research, puzzles, and complexity made me think this might help; at the same time, I was a little nervous about opening the door to students pontificating excessively about what they already knew without being curious and open to finding out more.

When we began discussing parts of the brain and their functions and why we tend to shut down under stress, this conversation happened:

Pasquale: This connects to windows and doors being open and shut! Because when it’s shut you shut down! And when it’s open it’s your thinking!

Sydney: It’s like you’re happy and excited and know what to do! And when you’re shut you can’t do those things because you don’t know what to do!

Taylor: The brain research was just like our doors being open and shut.

Seba: Your brain sort of shuts down when you get threatened. That might also be like how when your doors close.

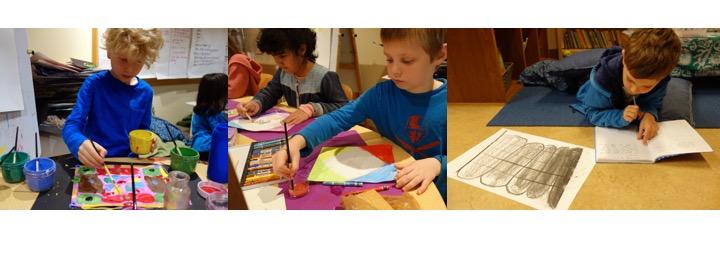

Learning more about how and why the brain functions, especially in conjunction with emotions, helped the students understand themselves in a new way. Learning that all humans have these experiences helped normalize feeling open and shut. I wondered if this normalization could also help us mobilize in moments of feeling stuck or shut down. I asked the students to think about how they might be more aware of when they were feeling open and shut and how they might be able to shift between. They went to materials and writing notebooks to explore these ideas.

Mijonet: You think you are feeling open and all of a sudden you slide into closed. It’s a little hard to go between but you can slide through the cracks and they can blow open.

I started to wonder if some people choose to stay shut and to wonder why they might do that. I realized sometimes it is easier to stay shut than to take a risk or try something new. I get shut down when I feel nervous or when I am worried about what someone thinks of me. It doesn’t feel good. It feels bad.

Jack: I made a painting. My dots were really close together. If you have an idea, then you think of something else and you have to figure which one’s right and then the doors close.

I went to kinetic sand to think about the space in between open and closed. The feeling doesn’t stay any one thing – it’s fluid – just like the kinetic sand! The sand doesn’t stay in one place; it moves and divides into pieces.

Anina: You can turn my picture different ways. Some people might think it is a river and other people might see it as a waterfall or rainbow. There is no right or wrong perspective and different perspectives can spark new ideas. If we all had the same ideas, there would never be any new ones.

Seba: The feeling of my windows and doors being open feels good. It’s like a train of thought but then once they close, the train of thought gets interrupted and then I get stuck and that’s the end of my thought.

I was curious if there are any benefits to having your windows and doors closed. If someone is always open, they wouldn’t even know the difference – but if you are closed sometimes, once you opened up, you would feel happier. If you know how to shift between these two, it will help you.

If you are always open, then you won’t know because you never experienced being closed.

In our conversations, it felt important to find balance between the idea that everyone experiences being open and shut – and yet, that very fact does not exempt us from a responsibility to be aware of and act on our feelings and experiences. Shifting between open and closed can be really hard; however, normalizing these emotions helped students be more proactive as they realized it was a shared, and perhaps even needed, human experience. As Taylor said, “We can’t always prevent the doors closing, because it’s going to happen, and if it never happened, you might not even know what open is. Like Anna said, if things are always joyful you won’t know what that joy is.”

Looking back on our time together, it might sound as though there was a fluid development of understanding supported by powerful discussions, rich experiences with materials, and deep reflection – and there probably was. However, it was not always smooth nor harmonious. It often felt hard. But, hard is not necessarily bad. Often what felt hard to me as a teacher was really a sign of deep engagement as students wrestled with complex ideas and worked to bring together their prior experiences, beliefs, and habits with new information and ideas. This disequilibrium is a critical part of learning.

What stands out to me in particular was how the students showed what they needed even if it was not what they wanted. Children are very good at telling us what they want. However, if we listen and observe carefully, they can also show us what they need. The children in Opal 3 not only helped figure out what they needed, they also helped to construct it, as the ball toss continued back and forth over the course of the fall.

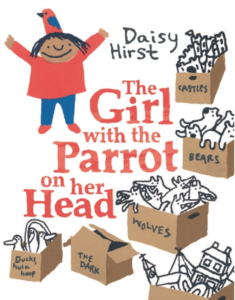

One way we often throw the ball at Opal is through discussions inspired by read-alouds. Often, taking the focus away from ourselves allows us to learn more about ourselves. One day, we were talking about Daisy Hirst’s book The Girl with the Parrot on her Head and I realized the students might as well have been talking about themselves:

Taylor: It’s almost like she was trapped with her windows and doors shut and she had to go outside of that place. She found what she actually needed. She didn’t actually need a box, she needed a friend.

Sasha: She was looking for something that she didn’t actually want. And then she found what she really needed.

Hannah: How does this story connect to the book What Do You Do with a Challenge?

Seba: In both books, when they had a problem, they found an opportunity. The girl lost a person, but if that didn’t happen, she wouldn’t have made space to find a new friend.

Ollie: The boy found that the next time he finds a problem floating around, he shouldn’t get more mad. He should work on it. And maybe he has more tools to work on them from the last time. And even if he doesn’t, he knows that he can try.

I was struck again and again by how willing the students were to go along with these investigations which asked them to take risks, be curious, and live in uncertainty – the very experiences I had anticipated being so challenging for this group of students in the beginning of the year as captured in my first blog post this year. Even when it was hard, even when they pushed back, they were still playing with and making sense of the big ideas we were exploring.

They also demonstrated greater stamina for challenge. As Ollie wrote in his notebook:

When you work on a problem longer, your brain grows. If we got used to having challenges, our brains would grow to the size of elephants. I think my brain is growing. If we get comfortable with things being hard, we could get smarter.

The Art Costa Centre for Thinking defines habits of mind as, “knowing how to behave intelligently when you DON’T know the answer. It means having a disposition toward behaving intelligently when confronted with problems, the answers to which are not immediately known: dichotomies, dilemmas, enigmas and uncertainties.”

Ollie’s words encompass both the sentiment in the Costa Centre’s words and in the shifts happening across the Opal 3 community. And still, I know, our work is only beginning.