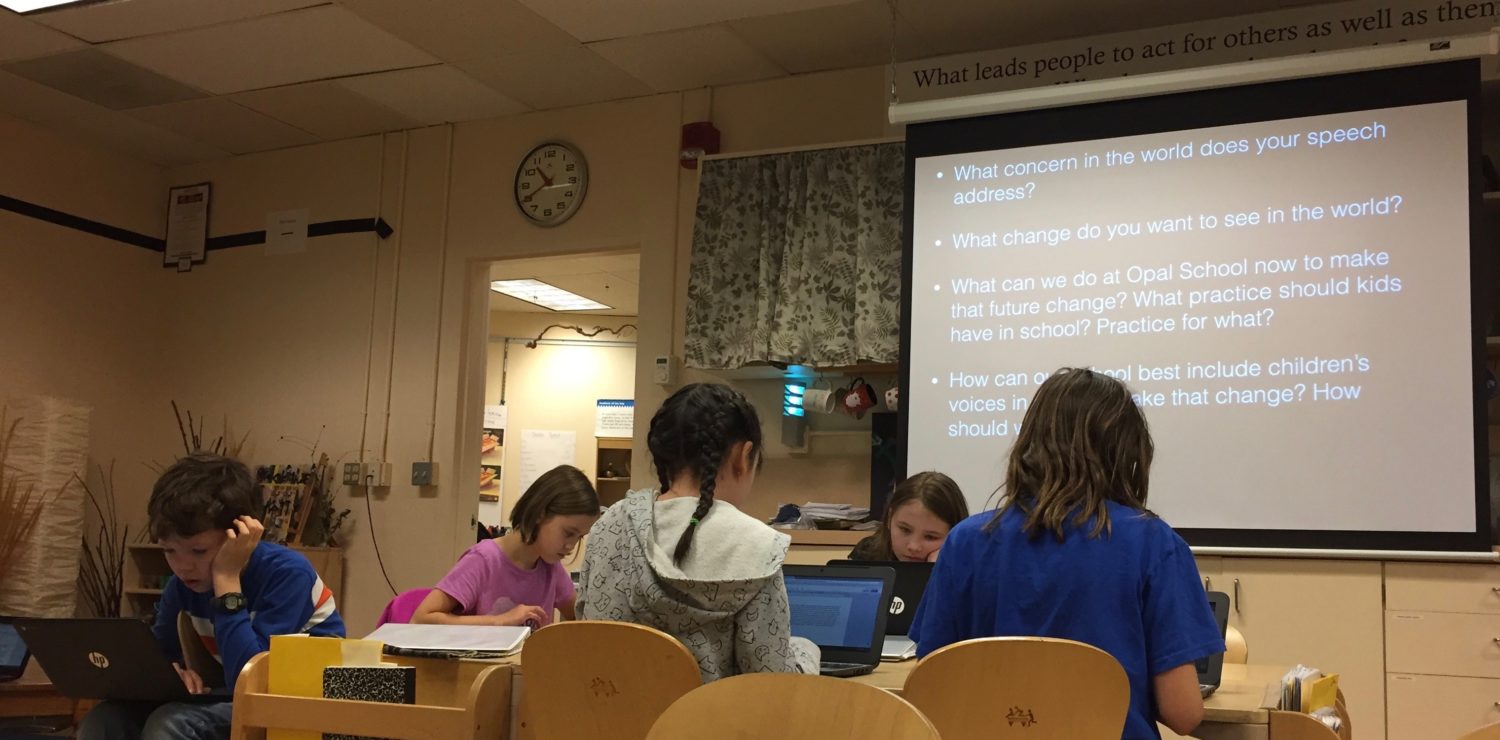

Is it playful inquiry?

Matt and I have been puzzling over this photo this week. Is this moment of questions posed and children deep into their research and writing representative of playful inquiry? Delight isn’t a quality that immediately jumps to mind. But joy? Perhaps. Play is not the opposite of work. There is joy in work. Especially as the children get older — these children are 9, 10 and 11 years old — though their play looks much like the giggly, imaginative, and rough and tumble of earlier years, my hunch is that their playful inquiry is different. Their materials are often big questions and words and they build ideas, they mess around with ideas, they share ideas, and they read the ideas of others. They are purposeful. Engaged. I have to shoo many of them each day outside to get fresh air and run their bodies around because they are begging me to stay inside and keep working. All 26 of them sustain work for two hour blocks and want to keep going, asking to take the project home to keep working. They are so eager to contribute and construct and so ready to matter.

So what are the characteristics of playful inquiry if it’s possible that it doesn’t always look “playful”? What do you think, Readers? What do we call this kind of deep engagement in purposeful work? Where does this happen for you in your own life? I know that I feel like it’s hard to stop most days in Opal 4. And I can’t wait to come back the next day. Is playful inquiry a condition that ignites passion, purpose and joy? Is playful inquiry a means to support the dispositions towards lifelong learning we want to see in the world?

I love that you’re puzzling over this photo! I see these moments in my classroom too – I agree with delight, joy, passion and purpose – it’s playful inquiry. I believe it happens in a community based on trust where the children know they have agency. And if you ask the children, they don’t call it work or play, but they know it makes them happy and they know they want more, more, more! <3

I think that’s so true, Levia! That children don’t call it work or play. And so interesting to consider because that means that our adult view of things, that wants to compartmentalize everything, may be clouding our ability to see what’s going on. Of course children will name work and play as separate things, but how much of the way they define them is influenced by our adult models, our adult interpretations? How often do we alienate children from sources of strength by delegitimizing their actions or ideas? It’s so hard for us to remember that the ways we see the world may not be the ways we’ll save the world. So passing those ways on may not be a great way to go!

Opal supports students to live and learn in their zone of genius. This idea is from Gay Hendrick’s book “The Big Leap”. You’re in your zone of genius when you’re doing what you love and what you’re uniquely gifted to do. At a younger age, the genius zone looks more imagination-based and expressed in manipulation of materials. At an older age, it emerges in problem solving, writing, sharing ideas.

The semantics of work and play are tricky because of the adult-world emotions and stories we attach to those words. Calling something “work” seems to exclude the possibility that it could also be “play.”

What I see at Opal is that there is acceptance and support for the range of genius that shows up in the classroom. And the activities that are presented in the classroom evolve to match brain development of each age, things happening in the world that the kids want to process, and interests of the classroom collectively.

Gay Hendricks says that when we’re in our zone of genius, all sense of time falls away, the activity is easy, and very fulfilling. As an adult, I am going back to learn my zone of genius after school and employers have rewarded me for working in my lower zones of excellence or competence. I love that Opal is teaching children what it feels like to live in their zone of genius, so they know how it feels in their bodies and souls, and that they can continue to live the rest of their lives in it as well.

Yes! I think that so often adults look at children through a deficit lens because of the image they hold of “genius.” At the same time, they say that they strive to apply a strengths-based lens. I think you’ve hit on the idea that doing this needs to be guided by building schools around the genius of childhood.

I love this idea of playful inquiry, and how it develops overtime and exists/looks differently in the world at different stages. How something can be joyful, and yet look like deep-focused concentration. I would be curious to know if their brain is perhaps achieving the same end goals/making the same connections, but in a different body state? It makes me wonder what playful inquiry looks like without play? And/or without the words/actions that we so often use when describing it?

Your questions and the conversation below left me thinking about:

1. The notion of flow and what happens in that state >> a state of playful inquiry

– How do we sustain playful inquiry?

– What structures are built into our day (as adults) to support + encourage different modes of playful inquiry?

2. Intrinsic motivation

– Recognizing what which is not always visible in playful inquiry

– Intrinsic motivation, autonomy, etc.

– Look at Project Zero, Indicators of Playfulness, May 2016 Draft

– How what is “visible” (in playful inquiry) changes with age/context/environment/materials/tools/etc.