Interdependencies

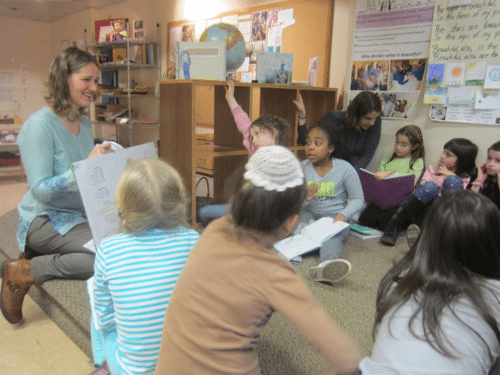

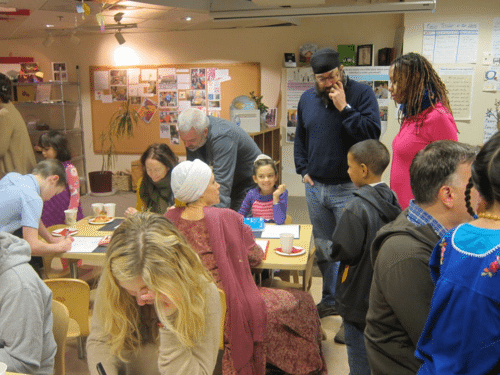

As children journey through Opal 1 and Opal 2, they spend a lot of time considering with their teachers and their peers the ways in which we depend on each other in this world.

What is a community?

What is our relationship to the natural world?

“The we that I am” — what does that mean?

In Opal 3 we become focused on supporting children to construct an understanding of what it means that we are also interdependent: that a healthy, thiving system requires a mindful effort to balance naturally competing forces, to be comfortable with paradox, and to negotiate conflict productively.

These are the big ideas we start with each year. Then we meet the actual children and we encounter the realities and opportunities that present themselves in a given time. This year, we have been presented with opportunities to take leadership on the playground project as well as to support the Museum’s bike exhibit. So a study of the design process has been an obvious point of entry. Attending to the design process has offered us an opportunity to consider power and perspective. The children have made such comments as:

“Not everyone in the world likes everything in the world.”

“You have to decide about your own happiness.”

“You can’t make everyone happy.”

“But I want to be happy.”

What rich learning the children have a chance to do in the face of the REAL work in being stewards of the playground project as it moves forward. As one child remarked: “I’m picturing everyone here, and I think they’ll all be smiling.” How do we take responsibility for ensuring so many smiles? If we all want to smile, how can it be that we have so many different kinds of things that make us smile? And what do we do about that?

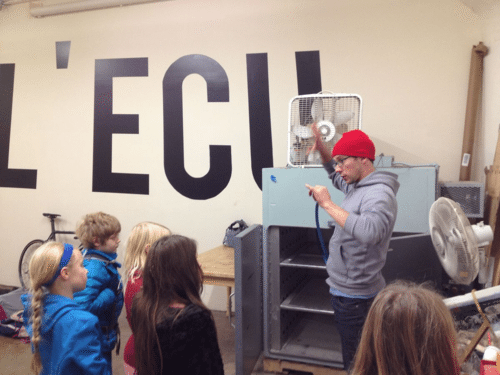

Meeting with bike designers around Portland gave the children a chance to talk with people who grapple with this dilemma every day. When a child asked “What keeps you excited about making bikes?”, Sascha White from Vanilla Bikes said:

I just love it. I like feeling that when I come in here, if I have an idea, I can take this picture in my head and make it turn out just the way I want it in real life. And to know the people who come to us for bikes are going to get so much joy out of riding a bike that we built for them, that’s a pretty big motivator for me because I feel like we’re making the world a better place a little bit.

Books offer another critical voice to our studies and dialogues. Before winter break, we read two important texts: Whoever You Are, by Mem Fox and Old Turtle and the Broken Truth by Douglas Wood.

These books helped us consider how we are more alike than different, but that the differences really matter. One child explained: Hearts are the same even though you might speak a different language or look different, and in Old Turtle, the message is that people can be from different places but you can see yourself in them.

In Old Turtle, the people find a truth that says “You are loved.” But they don’t realize it is broken and the world is at war over it until Old Turtle gives a child who is looking for help the other half, which says, “And so are they.” Another child synthesized the story this way: When the broken truth was in two then the world was kind of in two. The animals were having a bad time because of the humans and the humans were having a bad time because of the truth. And so when it wasn’t one the world couldn’t be one.

In all my years working through projects with children in this way, I’ve never been disappointed as long as I am listening. I know a concept like interdependence is a big one. And I know that part of the reason it is so big is that it is so rich with connection to our experience. So, although I may not be sure exactly what will surface, I can trust that there will be connections to use to build understanding. I can trust that if I am listening, I will hear points of reference that already live within the children’s knowing, and it is my job to pull those threads towards a loom that will support the weaving of new tapestries. Threads of this kind are captured through transcription (and other forms of documentation) like the two quotes above, offering us tools to use with the children themselves. These quotes will be returned to the children through future dialogue, further explored and expanded.

A thread of this kind was also presented when the children returned from their bike interviews having heard one of the designers talk about how he was inspired by balance. The child who had noted this made sure to elaborate: He wasn’t just talking aobut balancing on a bike, either. He was talking about balance everywhere in the world.

Old Turtle’s truth is full of balance. The design process requires balance. Healthy interdependence relies on balance. And so without even knowing yet that we are studying this concept — they already are. It is, in so many ways, their own wonderful idea. As Jean Piaget’s protege and Harvard scholar, Eleanor Duckworth writes, “The having of wonderful ideas is what I consider to be the essence of intellectual development.”

But also we must suggest opportunities for wonderful ideas to occur. We call those provocations.

At our Author’s Tea the day before winter break, an Opal 3 parent let us know how eager she was to have the students work on a story and study of their familes.

Here was another opportunity for connection handed to us from the present resource of our community. And, of course, what better way to dive more deeply into the process of understanding how similar and how different we are than by studying where we come from, how we got here, and the interdependent system that is our own classroom community, built on our capacity to balance needs – to work together to keep people smiling, and responding productively when they don’t.

So the provocations we have developed this week have been intended to support the students to uncover some thinking about family — their own, and everyone else’s. We have turned to excellent literature for inspiration.

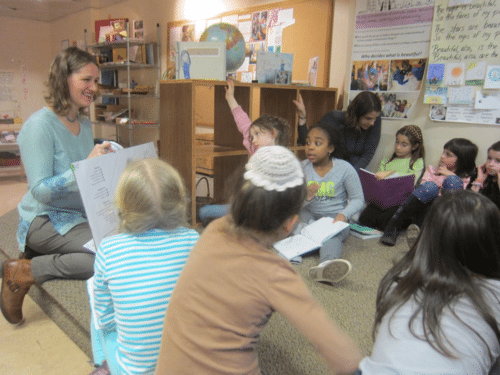

And we have invited the children to respond through writing, with materials, individually, in small groups, and all together. Children have brainstormed their own lists of family stories in thier writer’s notebooks and will continue to grow and develop those lists in the coming school days. Something from these lists will grow into a new writing project for each child.

As we’ve shared this week, we’ve been careful about paying attention to the difference between connections and sameness. For example, when one child shares the birthday tradition at her house, I might ask — “So who is reminded of their own birthday celebration? And does anyone say, ‘Wow! That’s EXACTLY what we do at my house!” We are intentionally seeking both same and different, and building the capacity to honor both — in balance.

This line of inquiry was itself a provocation. It was predictable that the children already knew that there was a common set of needs of every family, and I knew that in order to move towards the study of interdependence as it relates to family and community, we needed to generate that list. It is the list that will help us more deeply understand what it means to look at someone who is different from you and see yourself in him.

But I also knew it would have the most power if the list was the children’s wonderful idea. And sure enough, it didn’t take long. One child, in the midst of a group sharing from writing in writer’s notebooks, said, “Well there are some things that really are the same for every family in the world. Like, every family sends their children to school.” This child’s offering invited us/allowed us to create a list together of those nuggets of the human condition that live at the heart of our experience, no matter who we are.

I believe it is because of this list, generated collaboratively as their own wonderful idea in their own language, that they were able to read (teacher selected) short stories from Sandra Cisneros’ brilliant collections of family stories, The House on Mango Street, and Woman Hollering Creek on Friday.

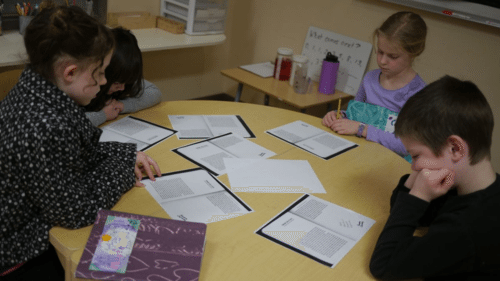

Though we selected, of course, pieces from Cisneros’ work that were subject-approriate for third grade, these are not texts that educators generally agree third graders could be capable of reading. They are short texts, but dense and dripping with gorgeous metaphors and descriptions. The children were asked to read, to work together to highlight lines that communicated strong experiences and emotions, to label those experiences and emotions with something from our list of things “all families have in common” and to then write the title or idea of something they might write themselves that connected to the same part of the list. If this isn’t the “essence of intellectual development”, I’m not sure what is.

Here are some examples of the work they accomplished:

One child found Cisneros’ line: … “inside that body too small to contain the hundred baloons of happiness” related that to the idea that all families have ups and downs and found her own idea: I sometimes get picked on and I feel as if my hundred balloons of happiness have popped.

Another child who read “The House on Mango Street” story connected it to the need for all families to have a place to live and wrote of her own need: My house is not like the house on Mango Street but it is not a huge house, either. We have a nice back yard and I remember when the big climbing tree got cut down and so did our fort and secret passageways. Now we couldn’t either pick plums.

And one who read “My Name” connected the piece to the idea that all families have hopes and fears. He wrote: My grandpa was in war. He got hurt. I do not want to be armed. I want to be a pilot.

In fact, I could quote the success of every child in making their own connection and interpretation of these sophisticated texts. It will be a joy to continue this journey.

I will spend time over the weekend thinking about the connections, pondering which piece to pick up and bring back, which thread to tie next to the loom so our weaving can continue. I’ll leave you with an example of a good bet —

“I was once 1 so I’m still 1 inside me now. You can’t say, “I hate babies” because that’s saying, “I hate myself”… It’s like you can’t say you hate any kind of person because you are going to go through that cycle, too.”

So much wisdom already lives within an 8-year-old.

It is nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry; for this delicate little plant, aside from stimulation, stands mainly in need of freedom; without this it goes to wreck and ruin without fail. It is a very grave mistake to think that the enjoyment of seeing and searching can be promoted by means of coercion and a sense of duty. – Albert Einstein

There is such enjoyment in seeing and searching. It is the joy of teaching at Opal School.