Going to Materials

One day recently, 4-year old Eliza was busy with an array of materials. Her teacher paused to observe her just in time to catch her words: “Materials, I love you. They can turn into love when you give them away.”

From the time babies can wrap their hands around an object, materials play a powerful role in our worlds, helping us build, create, and invent, not just buildings, creations, and inventions, but also ideas, understandings, connections, and questions to push our thinking further. We know materials have a power that can be unlocked with invitation, interaction, and intention. We know this because we see it again and again. We hear it and see it in 4 years olds like Eliza. We hear it in our graduating 5th graders, like Lina, who shared the following in her graduation speech in 2015:

When you have an idea- one of the big parts of growing that idea is putting it into a new language in art or words. It’s like translating. Translating ideas helps other people to understand your ideas better…. Before you translate your idea through words or materials, you know it’s there but you don’t know what it is or how it works. As you change your idea into something you can say or see that other people can understand, then you sort of understand it better yourself. It’s a way of understanding not just for other people, but for yourself. You can think you understand something but when you translate it into another language you really understand it more- what it is, compared to what you initially thought it was, is so different.

But what really happens when we go to materials? What happens in our brains and our bodies? What happens for us as individuals and when we work together? What does it even mean to go to materials? This last question was posed to me by my husband, also a teacher. He often asks me, “What are your students doing tomorrow?” and I’ll say something like, “We’re going to go to materials to deepen our understanding of …” and he says, “What does that mean, go to materials? And how? And why? And what do you do about the kids who will just play with the materials?”

These very real questions come up for me every time we “go to materials.” What are my intentions? Will the materials work to help students extend and deepen their thinking? Are they working for some students and not for others? Are some students just playing and making pretty things? What does it mean if they are?

I think back to my teaching life before I came to Opal, when I might have invited students to use materials to adorn or decorate when the “real” work was finished. I saw value in artistry and in illustrating pieces of work, but I did not realize the potential for materials to help get work going, elevate the level of the work while in progress, and add to the range of possibilities for the work. When I was new at Opal, I remember watching 8-year-old Samantha, stuck with her writing and unsure of how to get started. She had her notebook, pencils, paper. She’d sharpen pencils, get new paper, gaze out the window, get a drink of water, do anything – except write. She finally asked me if she could use some drawing materials to help her find her ideas. I was just about to say no, when Susan jumped in. “Sure,” she said. “What material do you think will help you?”

Samantha explained that drawing often relaxed her and helped her find stories because she often ended drawing kind of a story line through a series of pictures. Susan had her find the materials she needed to get started, and asked her to check in later to report back on what happened. “I’m excited to see what you figure out.”

So many things happened in that eye-opening experience for me. First, I was struck by the idea that Samantha not only could – but should – use materials to get her started. I also noticed that Samantha knew herself well – she reflected on previous experiences and prior knowledge to identify a material that could help her. Finally, Susan built in both a layer of accountability by letting her know she would check in later and a layer of trust and confidence with her assurance that Samantha could be successful. Sure enough, after 15 minutes or so, Samantha came back to report that she had found her idea and had already started writing. She said, “It’s better than I thought it could be.”

This memory comes back to me often when I face my doubts and wonderings around materials. It reminds me not just of the power of materials, but also that there are carefully orchestrated layers of work going into using materials. We build in all kinds of supports, scaffolds, and experiences to help students know themselves, know materials, and know what’s expected. When we see bumps in the way, we lean to find out what’s going on.

A few years ago, when I was working with 4th and 5th graders in the Opal 4 community, we thought a lot about metacognition and materials. This work most likely led Lina to capture her thinking about materials, languages, and translating above. Now that I am again working with the oldest students at Opal, I was curious about their thoughts on materials, so I asked them.

A handful of students were quick to answer:

Eleanor: Materials can inspire us. Sometimes if we are stuck and don’t know what to do materials can inspire us and help us with our thinking. And if you’re stuck with writing you can work with materials to help you get unstuck.

Calla: Material adds a third option instead of just writing it down. Sometimes when your ideas are really complicated it is easier to use a metaphor that is more common and other people can understand.

Oceana: It’s kind of like you’re going out to explore an idea and you find new ideas, instead of just writing where you have the whole idea in your head.

Maylin: If you only have a small thought it can help you expand your thinking and find more thoughts to connect to it. It’s also like a transferal – Sometimes there are things in your brain that you can’t transfer onto paper, but using materials can help you transfer it.

I was excited to see the connections between their words and what Lina captured in her speech. I was also happy to see what our graduating students would take with them when they leave in June. I still had lots of questions: Did their words capture all of the students’ understandings and experiences with materials? Do I hope and expect that all students even have similar experiences? Is asking a question verbally and inviting students to respond through talking a sufficient way for me to learn what students think about materials? What about students who may process and share differently? How can I better understand what students know and understand about materials? How can I make sure they are not just telling me what I want to hear?

Having these questions might seem daunting, like I am questioning myself, this work, or the role of materials. But it doesn’t feel that way, because instead, the questions come from my curiosity about student understanding and my hope that they are having meaningful experiences. They are research questions, much like those described in my recent post.

With these questions in mind, I decided to investigate further in the next occasions for materials in our classroom. Often, teachers will set up and offer an array of materials for students to choose from.

When choosing, they consider which materials will help them with whatever provocation they are working on and why. They then state these intentions before going to work. As they work, teachers will stop by and talk with them about what’s happening with the material, with their thinking, and so on. Because I was curious about the experiences of students who weren’t speaking up when I posed the question, I set out to gather information in a variety of ways:

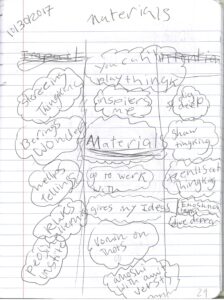

I asked them to write about materials in their notebooks.

I sat with them as they worked with materials and listened to their conversations.

I asked questions while they had the materials in hand to help them better find and explain their experience. While reflecting on our work with the refugee crisis, David said, “My structure represents how fragile everything is. It’s really hard to stay safe – it’s easy to get caught.” I asked him how materials helped his thinking, and he said, “The materials let me lean into how delicate it all is, and how dangerous it is, but as I built my structure I wondered if they would get stronger from the experience as they figure things out.”

I sat with another student also using building materials to reflect on new understandings about refugee experiences. As I watched her, I wondered if this was a case of using the materials because they seemed fun or perhaps even a distraction from the question asked.

So, I leaned in:

Hannah: How’s it going?

Petra: I just started building and it looks fun so I decided to do it.

Hannah: What’s happening as you do it?

Petra: I’m stacking.

I wasn’t sure if it was my questions that weren’t working for her, or if she didn’t understand the expectations, or something else. I didn’t feel that I was getting much from her and I wasn’t sure if she was getting much from the materials. I was not sure what else to do, so I persisted with my questions.

Hannah: What’s happening in your brain as you work?

Petra: I’m thinking about competition. Well, I’m just building this for a short amount of time. It’s not perfect. Louisa said she was doing more detailed work.

Hannah: How is material bringing you into your thinking?

Petra: Now I’m squishing them together. To make it more of my art piece. Before – it was just a regular structure but when I squish it in, it explodes. In the refugee book, it was a normal day and then out of nowhere everything changes. It explodes. I’m more aware of how things can change.

Both David and Petra focused on fragility and how quickly things can change in their work with materials. I don’t know if this is where Petra was going with the materials all along, or if she experienced an epiphany through using the materials, or if my questions provoked her understanding. I’m not sure it matters. What does matter is that the multi-layered process of using materials, digging into her thinking, and arriving at a powerful idea to continue thinking about did happen.

As I continue creating material invitations and observing students at work with materials, I am reminded of Ann Lewin-Benham’s thinking about materials.

Materials stimulate the senses, which respond by developing networks in the brain that in time enable us… to build relationships among complex ideas. Materials educate the hand, which drives language, movement, attention, planning, and scores of other brain functions. The combination of hand and materials is essential to virtually every endeavor.

I hear parallels between Lewin-Benham’s words and the thinking emerging through and about materials in our community. Just recently, in another reflection on materials, these words emerged and the conversation included new voices, speaking up to share their thinking:

Maya: I wanted to go to clay because I think clay opens up something in my brain to find metaphors.

Magnolia: At first, I made my piece of artificial things and it didn’t work and didn’t feel right. It didn’t match what I thought at first, so I tried again. When I was done, I realized I didn’t think about the question or the material the same way at all… I shifted so much – there was so much that was new.

Calla: It made me think about what it does for everyone and not just me. It made me think of other perspectives not just my own. The different colors represented the different perspectives and that made me think about those different perspectives.

I have some questions for you, Reader:

- What are you wondering as you invite students to use materials? What have you noticed while students work with materials?

- What do you do when you are not sure what students are experiencing with materials? How can you find out more? How can we reframe questions and provocations to find out more?

- How can we introduce children and adults new to the world of materials to the power of materials as tools for thinking, connecting, and reflecting?

- What happens for you when you use materials?