Diving into Project Work: Layers of Learning

- How can we make Colonial America come to life for 9 to 11 year olds living in Oregon?

- How are stories that took place more than 250 years ago and more than 3000 miles away relevant to children?

- What does it really mean to “dive deeply” into topics and ideas?

You hear from the teachers at Opal School that we “dive deeply” into the topics we study. As I see this work unfold in Opal 3, I am realizing that for me as a teacher, thinking about learning in layers is a paradigm shift. As I make sense of this kind of learning, an image that is starting to form in my engineer’s brain is not diving deeply into water, but into a stratified solid, like how one would find groundwater in an underground aquifer.

If you haven’t seen one of these images before, this is a vertical cut-away view of the earth. An aquifer is a layer in the earth where water flows. So if you were to dig a well into an aquifer, you would be able to extract water. In this image, the cleanest drinking water will be found in the deepest aquifer, the one called a, “confined aquifer”. This is not because the water has been there forever and is therefore more pure, but because it had to filter through so much earth to get there – it has been purified by the surrounding layers of earth.

So it goes with learning. The first part of the dive, into the surface water is necessarily shallow and less clear in that lacks context. While the student is just starting to play with new ideas, he or she hasn’t had enough time with the ideas to make meaning of them – to find connections to their own experience that will make the ideas real and alive, and to apply them in meaningful contexts. The water is somewhat murky.

Now, as we add more layers to the learning by reading stories, doing more research, and exploring through the arts, we start to move through the unconfined aquifer. The brain’s filtering process parallels the earth’s filters: sticky particles attach to what is already there, building context, schema and meaning. Wonderings, curiosity and imagination push through the aquifer and make the student want to know more.

We go deeper yet again by introducing materials, encouraging students to zoom in on the details in imagery to find even more sticky places to make sense of the content. Opportunities like this allow for that magic to happen — places years and miles away become vibrant and alive.

Riley said, “I felt like you could actually step onto the clay board and all the buildings would be life size and I could actually step into Boston.”

We become the scene in a field in our colonies – we are the corn, squash, farmers, slaves, livestock, and more.

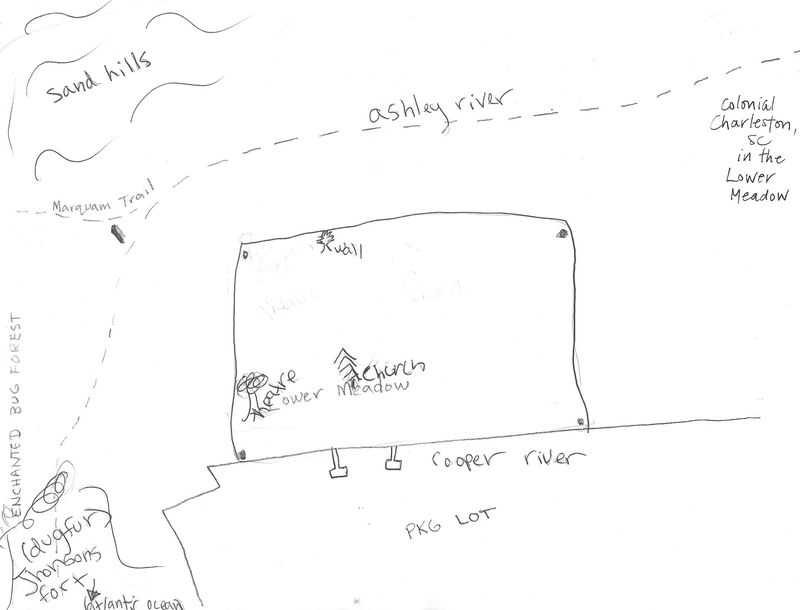

We also find children freely connecting, wondering and discovering as they play outdoors. This week I had the chance to take the “Charleston colony” to their territory in the arboretum during PE. They came to consensus quickly on how to map their colony on the lower meadow, finding all of the landmarks that they now know so well in 1750 Charleston, SC.

Once they know what all of the landmarks and places were in their space, they easily moved into dramatic play that was authentic to 1750 Charleston.

Max: They had balls made of cloth. We will bring the football and pretend it’s one of those balls. We’re going to play outside the walls of the city. We made up a game with the ball. It’s like rugby – you throw it back and forth and try to run it in. No overhand passes. If it’s “third try” you can kick it in.

Max: It’s a fun game!

What ball games did children play in colonial Charleston?

Teacher: Hey, you guys are outside of the city walls. What dangers might you face out here?

Danny: Snakes!

Max: Bears?

Danny: Indians, they could be hiding in the woods.

Teacher: How would boys defend themselves out here?

Max: They would probably have a sword and a pistol.

Karl: We could just lie very still.

Danny: I bet they had a pistol. Jasper Jonathan Pierce learned how to shoot a gun when he was 10.

What dangers were there outside of the city walls?

How did people (and young people in particular) defend themselves?

We’re taking baths!

Cooper to Maia: What kind of shampoo for you?

Maia: Watermelon Surprise!

Teacher: Do you think they had watermelon shampoo?

What kind of soap and shampoo did they use?

Cooper: Pigtails for you.

Ellie: We can tie my hair with bark, it’s flexible.

Cooper: They braided their hair and tied it around like this.

Ellie: What did they use for hair bands?

How did they take baths?

How did they wear their hair?

In the confined aquifer one finds flowing water that is free to travel along its gradient. This is the freely flowing understanding that a student can own. That water travels underground so that if anyone digs a well into it, they will be rewarded with clean drinking water. So too the student can access this deeply held meaning throughout their lives. They will be their own dowser, knowing when to dig that well and access that water.

How will we know when we are there? How do we know there isn’t yet another confined aquifer that is deeper and larger than this one? How will we be sure that every student has a chance to find their way along with their peers?

I see the power in giving my students many varied opportunities to play with their new ideas to see what is sticking and what they are asking to explore more. I see the power in listening and watching them make sense of all sorts of facts, ideas and stories from history, science, literacy and math all day long and seeing how that engaged learning helps to make them who they are and who they will be. I see the power in the class discovering together and feeling the energy of an engaged, curious learning community. And I see the power of discovering new, rich confined aquifers.

This is really a facinating look at what’s going on in Opal 3. Thanks for taking the time to share with parents. It’s so helpful to know the framework of this latest project.