Creating a Toolbox of Strategies for Conflict Resolution

After Community Agreements are made, they inevitably, regularly, get broken. What sounds good and reasonable and fair in the negotiation of agreements by community members who are relaxed, focused and engaged, can be difficult to remember in a moment of passion. That’s where the strategies come in!

Strategies are introduced or reflected on regularly throughout the year and practiced daily – if not hourly! Our image of the child – in fact, our image of the human being – includes the belief that ALL behaviors are attempts at belonging and connection and making meaning. Sometimes we mis-fire. Our efforts at building relationships are full of “oopsie” moments. 4-year-old Stella explained this well after she broke the classroom agreement of being safe and kind to one another:

I punch-ded Ruby today. It was an accident – ly. But it was an oopsie moment. I had an oopsie moment. Acause in my classroom we don't punch. We had to solve the problem. So I had to sit on the bench and my brain did something magical. I just thought 'there can be two mommies!' It just popped right in my brain. And everything just snapped together.

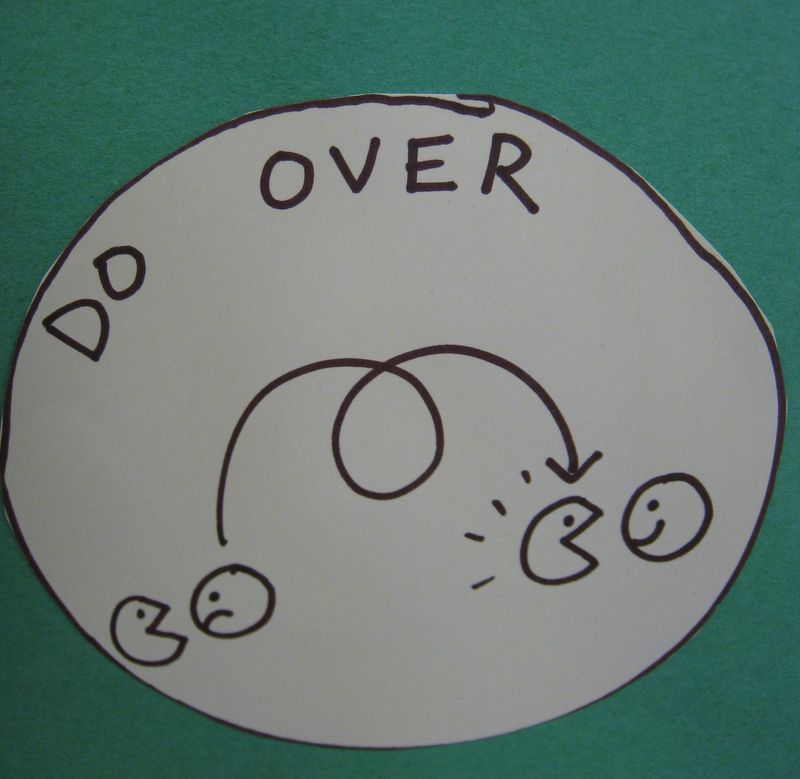

Stella beamed with pride as she recounted this incident. Not shamed for having made a mistake, but confident in the magic capacities of her powerful brain. And important in the context of school: ready to get back to the business of the classroom. Stella had used the strategy of taking a break, and was able to re-enter the play with fresh ideas for a do-over. Ruby as well, had most likely been supported to use a strategy such as giving Stella a clear message: "I don't like it when you hit me!"

Neuroscience is clear: the social-emotional and the cognitive parts of our brains are intertwined. But often the focus on cognitive development (read: academic achievement) that our culture (parents! Administrators! Policy makers and testing companies!) so highly values causes adults to deliver quick, often punitive fixes that work in the short run but do not support long-term healthy social-emotional growth OR the academic achievement that is possible when that is in place.

What might happen if we began to act on the assumption that children want to belong, that they deserve to belong, and that they, like all of us, are imperfect but worthy? What if we practice at the same time working from an assumption that learning and wanting to learn is as natural and pleasurable as breathing and therefore no less responsible to constrict in any way?

Here is a sampling of strategies that our school community has developed over the years:

- Give a clear message (example: “I don’t like it when you say I can’t play. It hurts my feelings.”

- Give a gentle reminder of our agreements (example: “Remember to not have a side conversation during Gathering.”)

- Ask a question (example: “Why are you not listening to me?”)

- Walk away/Take a break to calm down

- Ask for help from a teacher, a friend, or another adult

- Let it [the problem] go. Decide to not give it energy.

- Make a new agreement together (example: “How about next time…”)

- Do over – getting the chance to re-do the situation with new information (ex. Adjusting tone of voice, asking a question, sharing an idea to avert the problem, etc.)

These are not the only strategies we might introduce, and they might be different from classroom to classroom and for different grade levels. Not all strategies may be introduced in a given year.

New strategies are invented all the time. For example, one year in our classroom of 6 – 8 year olds, the teacher noticed that when some children were approached with a problem, they crossed their arms and sunk into a defensive physical stance. As she helped the children notice and reflect on this common stance, they wondered together whether a strategy of “being open” might be something to try. This new language became a deeply meaningful part of the conflict resolution strategy toolbox in that classroom. Because the teachers at Opal School all share a commitment to developing, using, and reflecting on these strategies with children, this strategy will be carried through the school culture in years to come.

Strategies are introduced over time, with lots of other support including dialogues, conferring with individual children, puppet theaters, practicing a strategy in absence of a conflict and much, much more. Videos included in this section of Opal Online feature a variety of moments between teachers and children as they work to put these strategies into action.

It is vitally important to understand that these strategies do not stand alone or work in isolation. Teachers would not ask a child to “do a do-over” without considering first who the child is and what the situation is and whether or not they have a clear picture of why that particular strategy would be meaningful.

For reflection:

What strategies do you regularly use in your conflict resolutions and interventions? If you named these strategies, what might you call them?

When do you observe children to be most engaged in conflict resolution?

Consider a child whose behaviors challenge you the most. How can you frame these struggles as failed attempts at belonging and relationship? From this position of empathy, what strategies might support this child to be more successful?

Consider the conflicts presented in your favorite children’s literature. How might you use the conflicts in books to engage your students in creating the language of conflict resolution strategies for themselves? As the character’s conflicts resolve, what connections can children make to their own struggles and resolutions?

I am the anchor teacher in Opal 2 this year and we are the class that came up with the need to stay open – before any conflict resolution could begin. Our agreements started this year with the idea of open. The kids decided that we needed to agree to stay open and “everyday is a brand new day.” It is a powerful thing to remind someone who is deep into “always” or “never” that we are just talking about today, this moment, since we have agreed to stay open. Being open has come to mean being open to a new idea or open to returning to a piece of thinking that felt too hard the first time. The wisdom and power in the work of staying open has made it into our everyday classroom lives in a hundred ways. Anyone have one of these small words/ideas that end up taking on a life of their own?

Can’t wait to hear… Zalika

I am a Kindergarten teacher and currently have a student who is very strong willed, defensive, and determined to be right in every conflict. Whenever there is a disagreement or a student isn’t following the rules of the game this student is quick to point them out and accuse them. When I pull the students aside to talk about the issue, he becomes very vocal and blunt with his words. His tone of voice and the way he accuses others hurts the other students’ feelings. Recently I was working with him on how he could use other words to express his frustration in a safe way that will still take care of his classmates feelings. I could tell this was a huge struggle for him. I think that point made about being open and not so defensive when dealing with conflict greatly pertains to this student. I have been trying to provide examples of other ways he could approach these situations and safe ways to talk to his peers. I have also asked him if he could give me examples of safe voice volumes, safe words to use, and other ways of explaining his frustration or opinion.

I’ve been using “I Care Rules” (from Peacemaking Skills for Little Kids) for a lot of years. One problem is that the conflict resolution strategies are the last to be taught. These articles are helping me think about how to use the same concepts more organically.

I especially like the “magical thinking” and how much ownership the student took of her own feelings and problem solving

Today is the first day of the return of one of our challenging boys (always right, very loud voice, elbow-sneaky blows to other kids). He has been with us all through kindergarten & the summer camps, he likes coming to the extended care program so we have a lot to work with…I like the idea of viewing his behavior as, “Failed attempts at belonging and relationship…” We will focus on the strategy of empathy and an early discussion as he returns to us…

Thanks for your comment, Lane. At last week’s staff meeting, we brainstormed a list of ways we approach social-emotional development at Opal School. Near the top of the (very long) list? “Believing that all people want to bring the best of who they are and connect and belong and that when they don’t, something has interfered – and we want to figure out what has interfered.”

My grade one students were inventing a game using 3D solids. One student became frustrated with his peers and turned away form them, arms crossed, face down, just as you described in the observations that led to the “Being open” strategy. I asked the group afterwards whether they could think of any ways to deal with these kinds of moments. One boy said, “Yes! Make a rule: NO BEING MAD!” Someone else said, “But mad is a feeling and you can’t not have your feelings.” He thought baout it and responded, “OK, the rule is: You can be mad but NO TURNING AWAY FOREVER. You can turn away to feel your mad feeling and then you have to come back and talk to us about our ideas.” They all agreed and the problem never thwarted them again. Amazing what can happen when they help solve the problems we’re facing.

As I read this article I was thinking specifically of one student that has had some social struggles this year. I loved the thought that “all behaviors are attempts at belonging and connection and making meaning.” This particular child so desperately wanted the love and attention from one friend that she was willing to do anything to get: yell, scream, push, grab, pull, throw tantrums and so on. My teaching partner and I decided we needed to work through strategies with her to help her move past this social sticking point. As a team we were able to give her the strategy she needed and help her learn to recognize when she needed to use it. The strategy that worked the best for her she nicknamed the turtle: tuck your head it, breathe and count to ten, then come back out and figure out how to respond in a friendly way.

I fully agree with the idea of what behaviors are. Next school year I think it will be my goal to help parents understand that theory as well!

The idea of behaviors are attempts of belonging, fitting in and making connections really hit home with me in this article. I always feel that when children act out in more negative behaviors it is because some sort of need is not being met from them.

I love the ideas on staying open and each day is a new day and what happens yesterday does not need to reflect on what is happens today. It is great reminders for not only dealing with students but for us teachers as well.