Confronting the disimagination machine

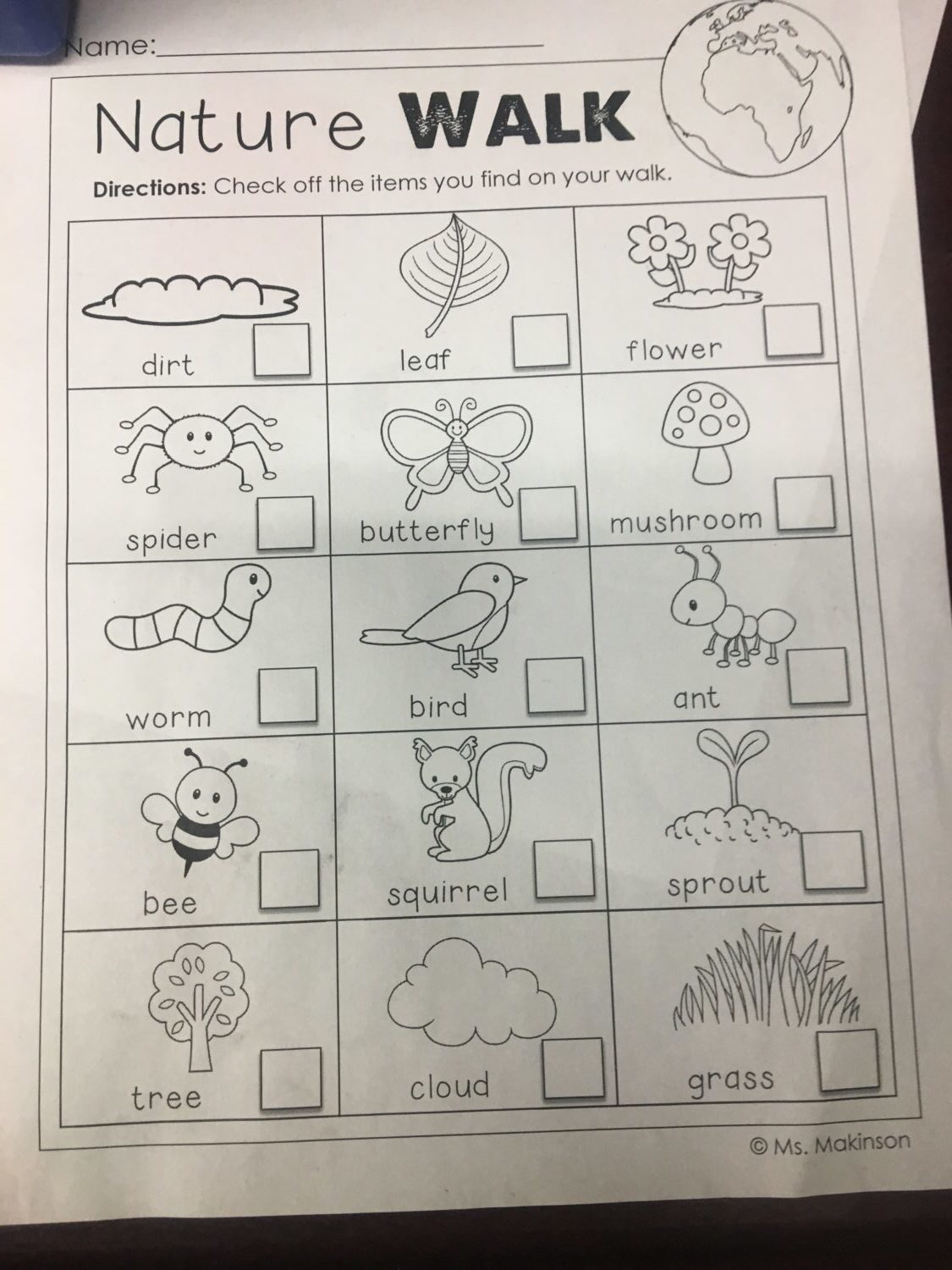

Friday, a frustrated colleague texted me this worksheet that a teacher in her school had given to the kindergarteners she works with on an “accountable walk” that day. My colleague wrote, “This is what the testing craze has done. Kids can’t even go for a walk without a worksheet! At my school, a ‘failing’ one, everything is about testing.”

It’s been a while since I had thought about a worksheet like this – perhaps because, like another colleague who wrote to me about the sheet said had been her experience, “I have been living and working in too much of a bubble for far too long. I forget the kinds of crap (like that worksheet – one of a thousand examples) that many, many students are exposed to – including my own, when I was just starting out.” I looked for a way in which the discrepant skills tested would be developed by the activity – and I didn’t see any. I couldn’t imagine how a child’s literacy skills would be advanced by using this sheet. Who is being held “accountable” to what?

I think that what my colleague was suggesting, though, is that the experience of the testing siege is not about developing the skills: More than being guided by outcomes and standards, it’s about being dominated by a stance that standardizes experiences and thinking to the point where the leaf in front of you is replaced by an anonymous line drawing. It’s about interrupting the child’s own powers of observation with “accountability” to see the “right” things on the walk. It’s a part of what Henry Giroux calls “the disimagination machine”– and which he responds to by calling on teachers to ask “what [is the role] of both formal education and the wider functions of education in a democracy? What pedagogical, political, and ethical responsibilities should educators and other cultural workers take on at a time when there is an increasing abandonment of egalitarian and democratic impulses?”

I assume this teacher is kind-hearted, well-intentioned, under-appreciated, and over-worked. How might we use this artifact to provoke some larger conversations: What does this activity indicate about the image held of the children who would use that worksheet? What capacities and competencies might this activity imply that children are bringing to the table? Of how they might participate in a larger community? What space does it hold for what they might create together? We could also move one step upstream: What does the publisher seem to be saying about the capacities and competencies of the teacher?

The worksheet seems so trivial, but it can be juxtaposed against other images to make the point. A colleague elsewhere in the world, inspired by her participation in our online Playful Literacy class, offered this note about her class outing on the same day:

On Friday, the kindergarten teacher and I had the privilege of taking our students to an outdoor learning and play space in our neighbouring community. We explored the concept of play and how play embedded in our teaching practices helps the children learn differently.

One of the requests we had for the students is to create something using the objects around them (sticks, pinecones, leaves, grass, rocks, etc.) and then tell an oral story. I then went around the space and interviewed the children about their stories. We talked about the fact that our creations were not permanent as they would be left in the space for others to enjoy. The oral stories that I heard from students were absolutely remarkable. Some students decided to recreate a traditional Aboriginal story from earlier that morning, some told mystical stories from foreign lands, and many told stories based on the spaces that they were in. Often times when the students would finish their piece I’d say “tell me more’ or “tell me more about _______________”. The conversations exchanged between students and teachers was remarkable and I can confidently say they were making meaning throughout.

When we cultivate engagements that inspire the construction of relationships between and amongst children, adults, and the world, we are participating in a political action with a different aspiration than when we ask children to limit their actions to drawing lines between the world and standardized images delivered to them. Both actions are political.

I’d love to hear from you:

What are you doing in your practice to inspire greater possibilities? How are you making sense of the relationship between your work and the development of a political imagination? How are you inviting your colleagues to join you in that work?

And related:

- Opal Online Sustaining Members are invited to consider the role of the arts as languages on this month’s discussion board.

- We hope you’ll join us at next month’s Summer Symposium (or one of next year’s workshops) to think together about how we are supporting children to invent the world.

Matt,

This is such an important post. Thank you. Your point (connected to Giroux’s) about the standardization of experience and thinking is powerful. It causes me to consider what other practices do the same things?

Thank you.

Thanks for reading and commenting, Steve. It’s an important question – one about which Giroux lays out some of the stakes. When you use that question as a frame for a walk around your school, what do you see?