Citizen World-Making and an Ecology of Listening

What does it mean to listen– to truly listen? When I think about this word, I think about what it looks like and feels like to give attention to whatever is unfolding at any given moment. As I began to reflect on this idea of listening, I was reminded of many encounters that I’ve had where another adult would come into the classroom and look around a bit confused before saying something along the lines of, “Oh! I didn’t see you there. I thought you were one of the children.” Whenever this has happened, I’ve just smiled and thought of it as a bit silly and delightful. It wasn’t until I started thinking more deeply about the act of listening that these comments kept poking up in my mind as a visible indication of listening.

I find a lot of joy engaging with children in conversation and play. I remember some of my first experiences working with children and genuinely being impressed by the things they created. I would marvel at a Lego structure — truly captivated by the architectural design a particular child created. I love the moments when you are invited for a cup of tea lovingly crafted of pine needles and flower petals…

The moments when a small hand reaches out to show you a treasure they found and you pause to feel the springy, wet texture of the tiny mushrooms. To sit in the grass and listen to poetry in a child’s own words from her little pocket notebook. It’s these small moments that captivate me into the world of children — their imagination, their words, their creativity, and their thinking. I find the most joyful moments in this work are when I am being present, truly pausing and paying attention to what’s unfolding.

What I love about these moments is the invitation into serendipity, the unexpected, and opportunities of exploring complexities the world around us has to offer. Thinking back on my years of teaching so far, the times that stand out, that are the most memorable and impactful, are the ones that weren’t necessarily planned – but instead came about through listening. I know this is true for my experience – that listening puts me in a space of joyful, immersive flow. I imagine this is true of the children’s experience as well: That school is best experienced by them when they are right down in it, listening to themselves and each other.

These are the moments where everything stopped or everything changed. Many of them are moments others questioned: What are you doing carrying that 25 foot branch into the classroom? These have been the most valuable moments in my work with children. Although not planned, they did not lack thoughtfulness and intention, rather the opposite. It was the moments when I had to be most thoughtful, most present, and most responsive to the moment. It is the moments when my values and beliefs had to drive what happens next.

Maya Angelou wrote, “I’ve learned that you can tell a lot about a person by the way (s)he handles these three things: a rainy day, lost luggage, and tangled Christmas tree lights.”

Perhaps the educator version of that might be something like how we handle: a first snowfall in the middle of a whole group meeting, the ongoing disappearance of pencils, and a collection of wet leaves being brought into the class.

Moments like these can be viewed as interruptions, or can be viewed as opportunities.

I think this is why I am often hidden amongst the children when someone comes looking for me. It’s because I want to be side by side with the children, hands working with materials, either chatting or sitting in silence, looking to encounter those opportunities. I want to be there because that’s where I find the most meaningful moments with children.

Ann Pelo compares this way of working with children to improv. She says,

“Improvisational theater is created at the moment it’s performed: it’s a collaboration in real time and space by the people involved, who don’t fall back on a script written in advance. The overarching rule of improvisation is to say “yes” to what you’re being offered by another participant, and then to add your best offering— something new, a provocation, a gesture, a musing, or a question intended to keep the exchange going.”

I love this idea she has of teaching as improv. It gives a name to just what I think this way of truly listening and being present as a teacher looks like and feels like.

In my years working with children, I have spent time mostly with preschoolers, first, and second graders. I was familiar with what it was like to get lost in the wonders of the natural world, play with materials, and question how we navigate relationships with ourselves, one another, and the world. This year was new for me. It was my first time working with third graders. If they didn’t hand me a fuzzy caterpillar that they named Bob this year, I was excited to find out what these third graders were going to invite me into. What would captivate their interest? What problems would these children want to solve? What contributions would they want to make?

As I mentioned earlier, being present to the unexpected moments isn’t without intentionality and thoughtfulness. I do think that unpacking what you value and believe about children, and thinking about what you are interested in researching drives and anchors the work and decisions we make.

At Opal School, grades 3-5 teachers meet together weekly. Early in the year, the intermediate team set our focus on playing with big ideas that strengthen our abilities to take perspective and think interdependently — two critical habits of mind for citizens in a democracy. What would citizen world-makers look like with this particular group of third graders, in this particular time and place of Portland, Oregon?

I imagine we all have a slightly different mental image when it comes to what citizen world-maker means to each of us. As I’m still growing my definition of what it means, I’ll share with you some things that come to mind. When I think about citizenship, I think of a sense of belonging to something greater than yourself. I think of multiple spheres with which that sense of belonging exists — personally, locally, and globally. I think about people who care about each other. A desire to understand one another through taking on different perspectives. I think of citizenship as participatory, collaborative, and playful. When I think about world maker, I think of a stance that’s not passive. That you consider the world as not already made but rather as something adaptable and influenced by everyone around it. I think being a world maker is a decision to participate in the things that you really care deeply about with a desire to learn more. I think it’s not being afraid to have ideas that bump into each other, knowing that the world is full of complexities and multiple perspectives. It’s working collaboratively to imagine possibilities and make a change.

I’ll share a few moments from our class this year that helped me to grow this definition.

Shortly after the school year began, youth-led global climate strikes were taking place across the world. Knowing that our intentions were rooted in exploring interdependencies and global citizenship, I considered how these youth-led climate strikes could be an immediate offering from the world around us. With the strikes taking place only 13 days after school began, I was asking myself is it too early to introduce? Am I really ready to open this door when we’re still working on signing in in the morning?

Ready or not, I decided it was important to bring this video made by one of the youth organizers that shared the intention of the global strikes to the class. If we want children to participate as world-makers, we have to make space for what’s happening in the world around us and consider the civic responsibility children have as participating members of a democracy. To do so involves acknowledging and inviting the world outside the classroom to intersect with the world inside the classroom.

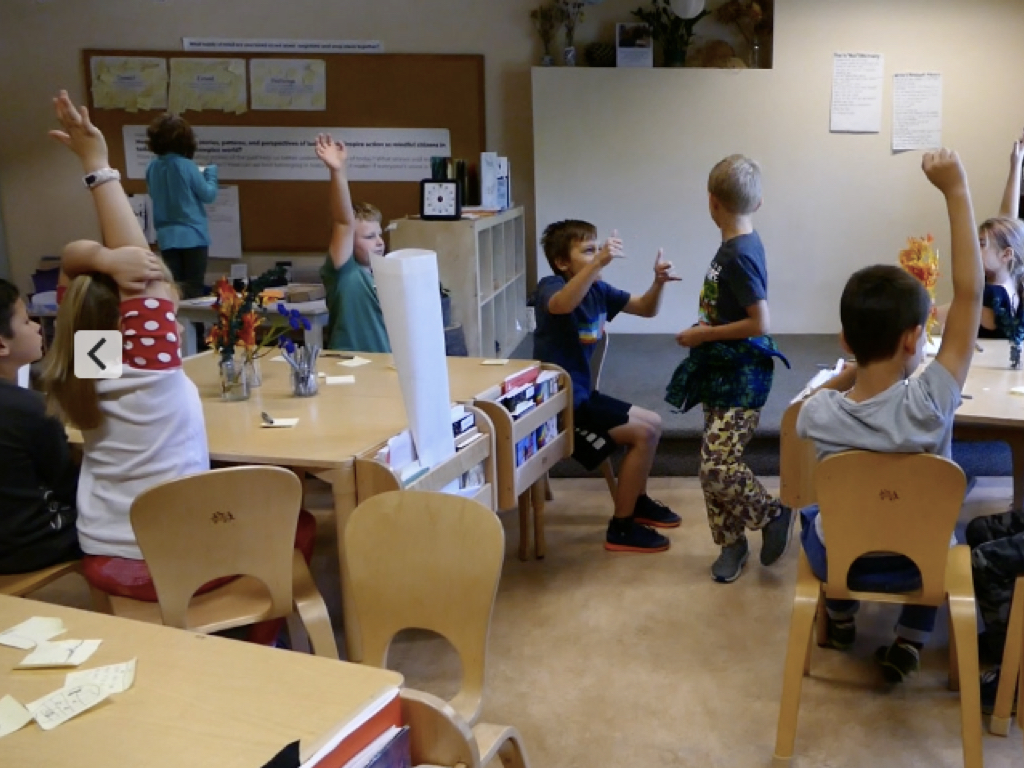

As the children closely watched the video, I closely paid attention to them. You could feel the emotions in the room. Eyebrows raised, sighs exhaled, bodies leaned forward. I invited the children to share their thoughts, excitement, and worries. The children immediately connected to the issue and sought more information in order to take action. They got up from their seats, walked up on the stage, and shared what was on their minds.

To listen means more than to hear someone. To listen means to accept the full range of emotions. The emotions that get stirred up gives rise to a sense of engagement and purpose. A sense that we can do something, we should do something, and must do something. Part of being a world-maker to me means that you don’t see the world as static, but as a place that can change and that is influenced by the actions we take.

Mira goes on to say, “I’m still stuck on what we can do.”

And Wilco responds with a question that invites us to play with that uncertainty. He offers, “Could people make a machine that could suck up all the gas and put it where it couldn’t bother anything?”

Saying “yes” is the core of improv. Wilco’s question was an offering I wanted to respond with a “yes” to because of the energy around this issue and the creative possibilities children can imagine. To envision a more improved world requires imagination. Rich with this gift, children dream up unique ideas and possibilities. Wilco’s invitation to invent this kind of machine sparked others’ imaginations almost immediately.

Some children went to work on making schematic drawings of an airplane that would run on pollution, sucking in polluted air and releasing clean air. Another child illustrated a machine that would respond as water levels rose, sucking up the additional water and turning it back into snow. One child reflected on her group’s work saying, “[Our] idea was to make a windmill that the stuff that is causing the greenhouse effect will be swooped away. But this is where I got stuck, where is it going to go?”

As with any design process, the dreaming and ideating can often lead us with more questions, puzzlements, and challenges. To reach out to others and say “I’m stuck” invites collaboration. It’s a disposition to see world making as complex, and co-constructed.

Others in the world were asking themselves similar questions as Wilco’s invitation to make a machine that could suck up all the gas and put it where it couldn’t bother anything. I found this video in which George Monbiot addressed Wilco’s very question stating,

“There is a magic machine that sucks carbon out of the air, costs very little, and builds itself…”

“It’s called… a tree.”

I knew this group of third graders had a strong relationship with the natural world, in particular trees, over the years and so I decided to bring this video to them when they expressed their stuckness in their inventions.

Upon hearing about this magical machine, the room erupted with delight and satisfaction. A sense of “Of course!” rang throughout the room.

We took some time to reflect on this realization.

August: When I first heard about climate change, I was really scared. And then once I heard that trees could stop it, I was like Yes! There’s hope.

Ben: Take time to look at it, absorb it, feel how important this tree can become. The power of nature.

One group expressed ‘We can start using nature’s tools’.

Considering how excited the children were by this magical machine that sucks in pollution and cleans it, I was curious about what other natural solutions we could uncover by investigating the natural world and tapping into our imaginations. It turns out there is a field of study in the world for this called biomimicry.

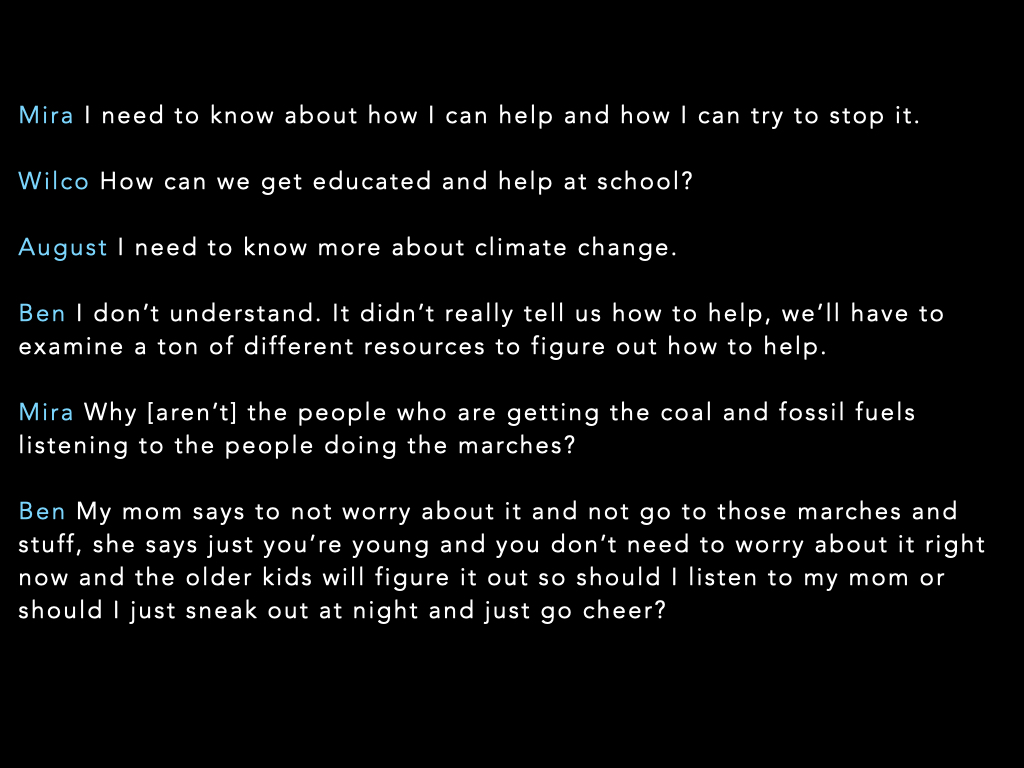

Biomimicry is just as it sounds; mimicking or imitating the shapes, process, and forms found in nature. Like the children said, “We can use nature’s tools.” To unpack this concept we engaged in a question protocol — where the children simply call out questions without any answers or judgements.

Here are just a couple of the dozens of questions that came up from this.

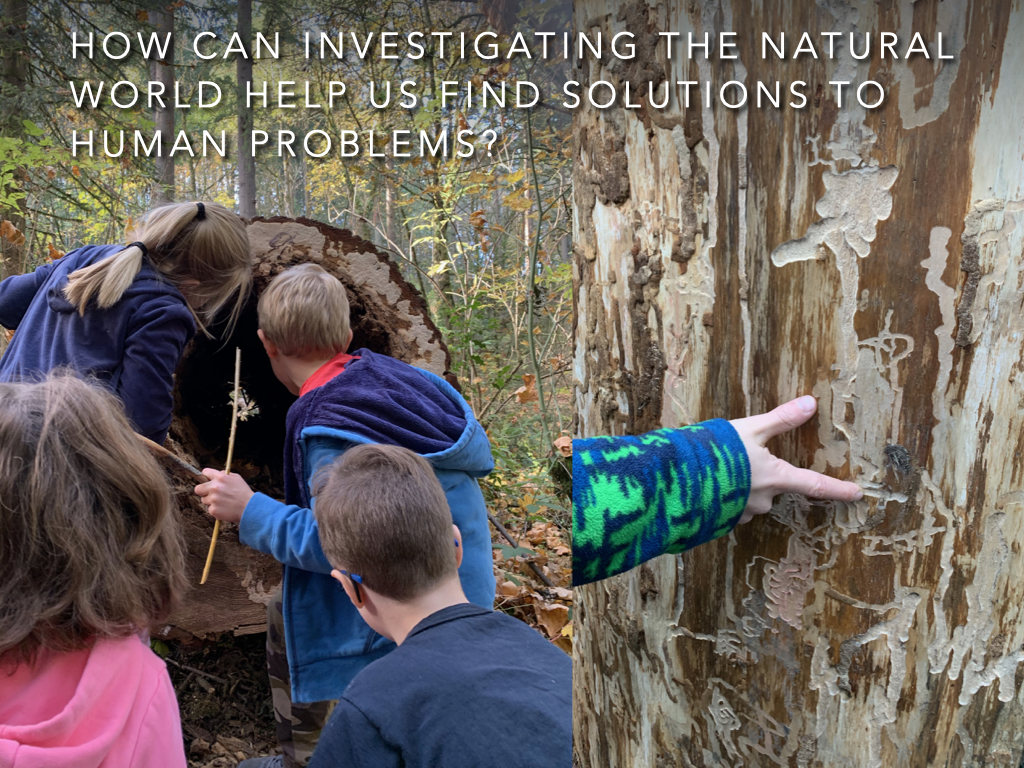

After thinking over the children’s questions, I compiled them into one guiding question: “How can investigating the natural world help us find solutions to human problems?”

We began by breaking down this question into smaller pieces. First, taking time to slow down and think about what it means to investigate the natural world, using all of our senses and turning to the arts to help us see ordinary things differently.

Then we looked to examples of biomimicry in the world. The children translated these ideas using materials to model the relationships between natural phenomena and human inventions.

We returned to that guiding question to zoom in on identifying human problems; considering “What are some issues humans face that might be solved through biomimicry?”

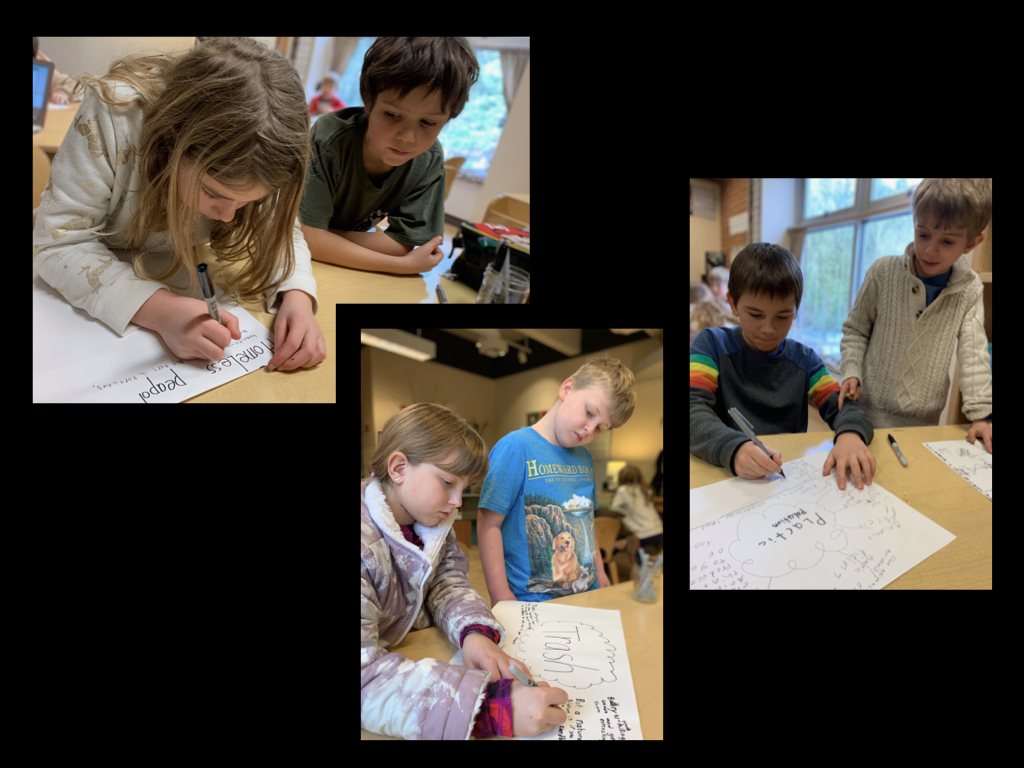

The children began brainstorming a variety of complex problems. Everything from the rules of four square, to communication and disagreements in our classroom, to the housing crisis in Portland, to climate change and trash pollution in our world. They began to see problems existing in a variety of spheres — ones in our school, in our city, in the country, and globally.

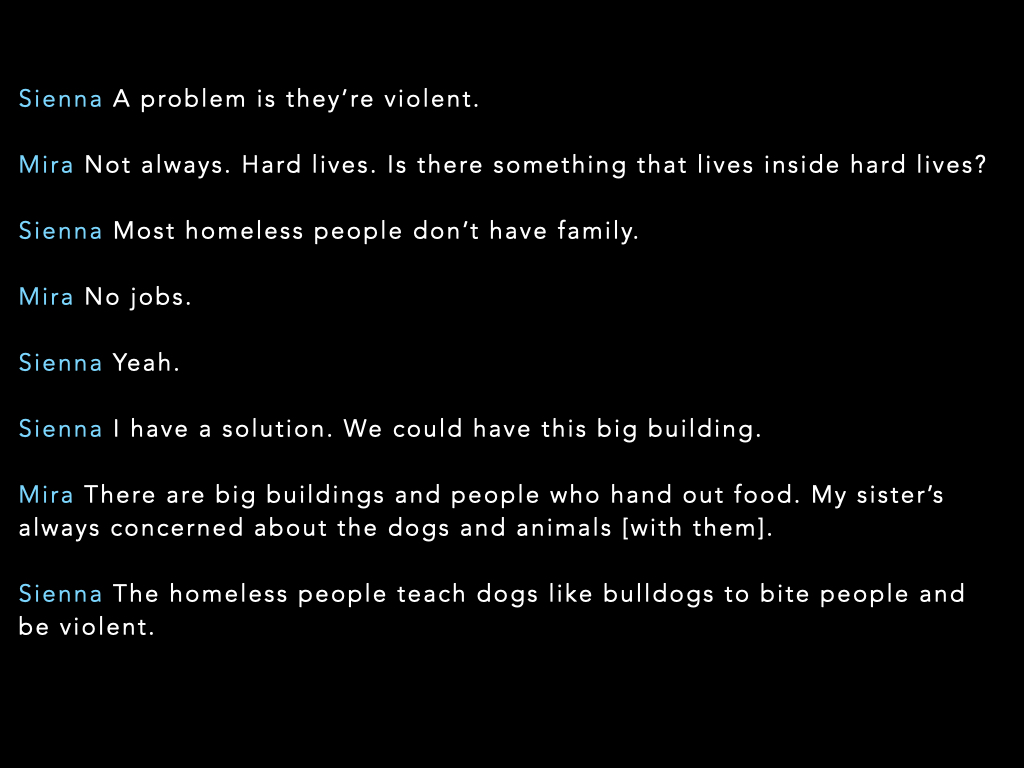

After identifying many problems, I asked groups of children to consider choosing a problem that feels particularly important to them and unpack what other problems might live inside those problems. I sat with one group who had chosen to discuss homelessness in our city. I listened carefully as their conversation unfolded, and I heard two very different perspectives.

Sitting with these children, I could feel this was one of those unscripted moments being presented as an offering. I knew my intentions were grounded in perspective-taking but did not know exactly how that might manifest. I was curious about— and listening for— other perspectives children may have so as a class we continued to unpack this particular issue deeper. While we dug into the complexities, we sought to both understand the specifics in these problems and the relationships within them.

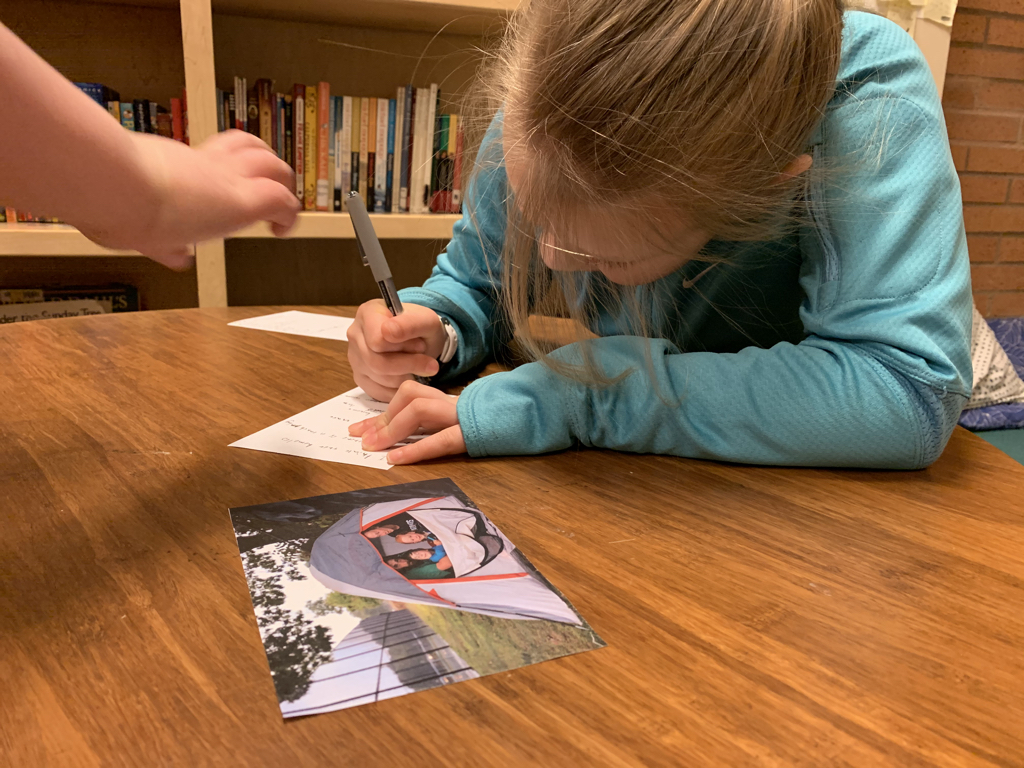

To do so we cracked open the word to share what might live inside of it. We looked at images and infographics to expand our thinking about who is included in the issue. We watched videos from the perspective of people experiencing houselessness to hear about life in their own words. We debated opinions about an upcoming measure for increased funding on the May ballot. Experiences like these gave us space to understand the issue more fully, take perspective, and grow our thinking.

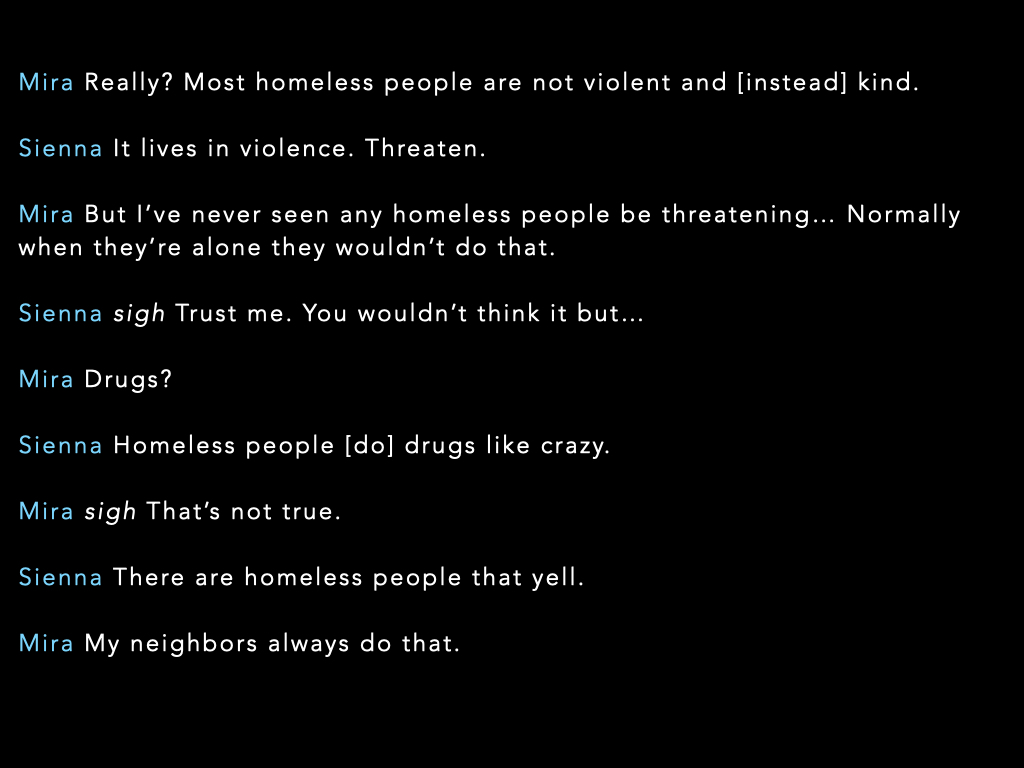

As they listened closely to one another, children were open to differing thinking and perspectives and allowed themselves to be changed with new insights. In her initial conversation with Mira, Sienna originally had a predetermined opinion on people experiencing houselenssness. As we dug into the issue her curiosity replaced her certainty:

Her tone shifted as she said, “It’s really confusing,” when we cracked open the word.

She sought more information when she said, “I want to see the article again. Who is it based on? Is it based on Metro?” when we researched the upcoming measure on the May ballot.

Her ideas of what lives inside the word opened up as she viewed people experiencing this issue as more than violent, saying “Someone that wants help. [Someone who] has to take risks.”

She considered ways people are currently helping when she said, “At New Seasons, you can pay it forward with a bean for hunger or wildlife. Companies can give money too.”

She asked herself and the class about what they could do:

“Can we do something to help them in our community?”

“If you think something happens to a homeless person, what do you do?”

“Can we make a separate area in our houses to invite homeless people in?”

I think Sienna’s deeper research, openness, curiosity, and desire to act on this particular issue is just one example of what it can look like to begin participation as a citizen world-maker.

I’m continuing to grow my understanding of what it means to be a citizen world-maker. In this story, I think it means embracing the complexities and uncertainties in our world. It’s being able to explore our own thinking and perspectives, and to listen deeply to the thinking and perspectives of others. To ask questions and be curious about what others think, do, and say. And to ask yourself questions about what you think, do, and say. It’s to investigate the implications of our thoughts and actions on the world, and to see them as a valuable piece in the interdependent nature of our world. It’s a belief that what you care about and do matters.

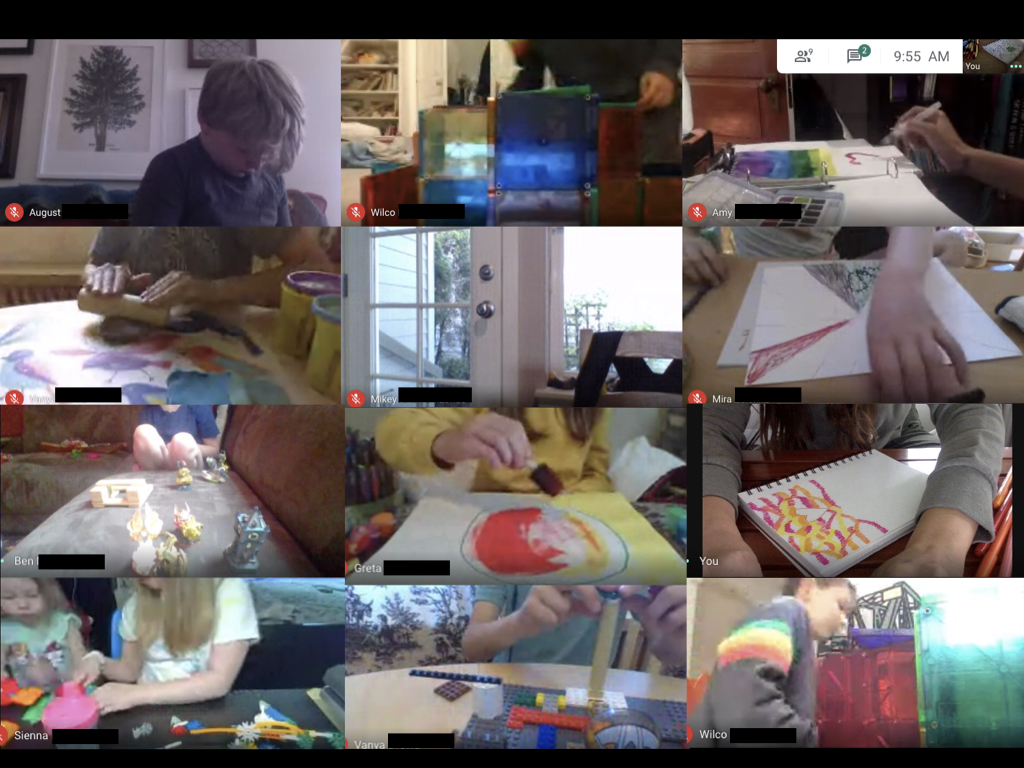

This year, more than ever, was a glaring reminder of just how quickly plans can change – as school quickly moved to distance learning for the remainder of the year. I am curious how this work would have unraveled as we continued to play with these ideas had we been together the last three month of school. But we’ll never know and I actually am pleased with that (after a few other emotions of course). I’m okay with that because that’s what this improv work actually is; it’s walking with the children and responding to opportunities in each living moment instead of a predetermined story or set of outcomes.

Whether we were focusing on issues in the classroom, in our world, or in the digital space, I believe that through the year we built important understandings about the world through unpacking our experiences, perspectives, and relationships with each other. I think that paying attention to what each of us had to say helped us make sense of issues going on in the world and develop a deep connection, concern for, and commitment to bigger issues.

Regardless of how we come together post-pandemic, or what age of children I work with, or whether they’re handing me caterpillars named Bob or a question about climate change, I want to be present to each living moment and say “yes” by responding with my best offering. I want people to have to continue to look hard around the room to find me because I’m side by side with the children, listening for those opportunities to dive into the work we don’t fully understand and accept the invitation to go deeper pondering what it means together. To engage in an ecology of listening, is to allow ourselves to step into the story, explore our questions, confront uncertainty, engage in dialogue, and ultimately marvel at the ambiguity one day at a time.