What Happens After the Mistake?

I made a mistake the other day. It’s probably true that I made more than one. But the one I’m thinking about, the one that kept me up that night, is the one I know I made for sure. I know because people have told me not to do the very thing I did. And I did it anyway.

You see, I’m impulsive. And I can be combative. And if I happen to pick up my phone after I should already be sleeping and find messages there that worry me, I have a habit of responding. Okay, so two mistakes. Or maybe three. Staying up too late. Checking messages on my phone before bed. And letting my impulsivity result in the sending of messages that will very likely be received as combative and make people feel angry at me — instead of being willing to help me, which is all I really wanted. These are things I know. I did them anyway. And because I’m aware that the people I care about don’t like it when I do what I did, I really wish I hadn’t.

Human beings want to be good. We want things to be good between us. In spite of the contrary evidence around us on the news and in our social media feeds, we really do. We want our actions to match our values. We want to belong. We want to do the right thing. Don’t you?

But we make mistakes. As we’re moving along, doing the best we can, we make mistakes. This subject has been the inspiration for many a classroom poster featuring cats and slogans like, “Mistakes provide the next lesson,” and “Hang in there, baby!” But what always seems to be missing is any clear image of what it is we are being encouraged to hang around for, presumably on the other side of that next lesson — the one the world is about to dish out to us, usually without warning. Mistakes become mistakes only after we realize that something didn’t go as planned. What feedback do the cats get? Are they yelled at? Punished? Put in time out? Shamed? Ignored? Pitied? Suspended from school? What happens next matters. The story we tell ourselves about the mistakes we’ve made are profoundly influenced by the stories being told about what should happen after a mistake is made. Every time these stories collide, there are lasting implications for the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and the extent to which we belong.

Without an intentional awareness of the relationship between what happened and what happened next, over years, mistakes become the ends of paragraphs in long life stories followed by lines filled with efforts to shield ourselves from the shame we feel because we have lost the ability to tell the difference between what we do and who we are. Without an intentional separation of these two very different things, mistakes come to define us. As we get older, depending on the effort it takes to carry this shame, we look for ways to manage the load. Medication, alcohol, food, technology, self-harm, and power can all function in one way or another as anaesthesia for the feelings of being afraid of the mistakes we’ve made and what will happen when we make more in the future — afraid of being wrong, of losing control, of not belonging, of being unworthy of love.

What if, instead, we thought of the the things we do as practice – just practice? What if the things we do and say in our efforts to be the best version of ourselves we can be are seen as the best we can do in the moment? In practice, we expect to engage with our imperfections. In practice, mistakes are things we do and we make — not who we are. In practice we get do-overs. And in practice, we expect mistakes to happen. We plan for them.

I’ve learned about do-overs at Opal School. Caroline Wolfe, one of Opal’s founders and a current Beginning School teacher, helped me learn to see all the things children do as efforts at belonging. Some go well. Some don’t. Both get do-overs — opportunities to reflect and encouragement to try again in order to keep the focus on feeling what it feels like when things work out for everyone. That doesn’t mean that when a child hits another child in order to get a particular block they think they need, and the other child cries, that the child who hit goes unpunished. Watching a friend cry because of something you have done is a real kind of punishment. The rise of panic and denial are often immediate. Timeouts and other forms of exclusion reinforce those feelings, and serve as confirmation to this child, the one who was hit, and all the others around that this child doesn’t belong. This child’s imperfections make him unworthy of love and belonging. And the person granted authority to exclude sends a clear message to all involved that making mistakes risks your membership in the community. We become conditioned to mind the rules, and less inclined to consider the part we play in the game.

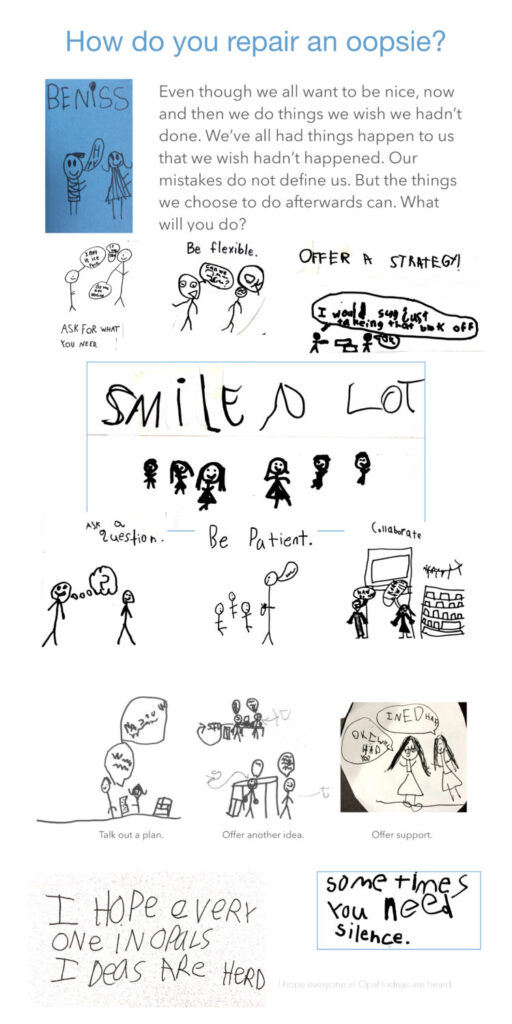

A do-over is an acknowledgment of the mistake. It is real accountability. But it also creates space for cooling off so our brains can start thinking again — so they can recover from the panic. There is time to attend to the hurt — both the hurt of the one who was hit, but also the hurt of the one who understands his actions have just risked his belonging. And then you do it all over again. Without taking sides, the teacher coaches the children through an alternative scenario that works for everyone. We ask: “What else could have happened here? What other choices could you have made? Do you want to try that again?”

Our drive towards belonging is so strong, and experiencing success through the practice of these new possibilities and strategies feels so good, do-overs are tremendously effective at re-wiring the pathways in our brains that lead to old habits.When our goal is connection, once we have a strategy that works, we tend to use it again. Once we understand that we are worthy of belonging, we tend to be able to see our behavior as practice, and are willing to try again when we make a mistake. Do-overs create new pathways that lead to what works.

Even though I did not grow up in a world that offered me do-overs, teaching at Opal School has helped me learn to use them. It still makes my stomach curl up to think the sentence “I made a mistake,” let alone to type it and hit publish here. But I think I’m willing to do it because even though my old habits got the better of me, this time my awareness had been heightened enough that I could go back and fix the mistake I made. My community had the courage to give me feedback that was hard to hear but that was clear and not punitive, not filled with blame. And so, when I made that mistake again the other day, when I did something because I wanted to draw my colleagues closer but pushed them away instead, I knew to take a do-over. In so doing, I am able to accept that, through another lens, my impulsivity and combativeness is really the same tenacious risk-taking that makes good things happen around here, too. Context matters. We need to develop a willingness to take ourselves into a variety of contexts, with our varied temperaments and dispositions and cultural perspectives, and practice bumping into each other. And then being curious about what happens when we do because we know that we all want to be good and we all want to belong. So when things go terribly wrong — there must exist a way to make them right again.

People don’t do better when we make them feel worse. They do better when they have better options.

We are a species that likely has the capacity but not yet the ability to know everything there is to know about our own plastic brains. What we do know — and what we didn’t need science to help us understand — is that we need one another to survive as we attempt to live together through generations. This is not a performance that will come to an end with applause and ovations. So especially in our work with our youngest citizens, when we treat mistakes as though they’ve ruined the show, as though we’ve sacrificed the encore, we deny ourselves the opportunity of making something beautiful together, the reason we were motivated to practice in the first place.

This is a really beautiful post. I would like to practice do-overs in my classroom. We have children who make mistakes with their friends take a break, which we only do if the action has been repeated multiple times and we have given them reminders or helped them problem solve in other ways first. We don’t consider this to be a punishment but time to breathe and take a moment to recenter…but in the end the child might feel like this is a punishment because they are being excluded/separated from the rest of the community. I really appreciate the examples of the language your learning community uses around mistakes and would love to hear more examples if you have them. Thanks for sharing your vulnerability about mistakes, it helps me to share mine.

Thank you for your response, Patricia. I talked with Caroline a little about your comment. We reflected on the role of boundary setting — the importance and value of boundary setting — even when that is sometimes hard for everyone involved. Your comment does make me wonder about how we can be sure when something feels like punishment, or shame, or blame, or consequence, or bumping into a boundary. Is it in the energy we use to give our feedback? Is it in our own intentions — and the story we are telling ourselves about what will make this child do “better”? Is it something the child clearly wants to learn and know how to do — even if they don’t know it yet? Can we ever be sure? Can we get better at being surer? I describe my experience alongside my own child’s experience with such boundary setting when she was in Caroline’s classroom towards the end of my TEDx: “School is for Learning to Live” which you can google if you like. And we have more posts in the works on this subject — so stay tuned and thank you for your willingness to engage in the conversation with us. We love that!