Thinking about thinking

In their earliest years at Opal School, students are introduced to the big word, metacognition, with the simple meaning: thinking about your thinking. This is a habit of mind we believe to be most critical for success in our society today. Being able to skillfully think about your own thinking affords you access to a range of strategies to use in any cognitive task or social/emotional interaction. Metacognition is the basic access point for all high level intellectual work: synthesis, inference, reflection– and the kind of mindfulness that allows you to access your emotional intelligence as needed in any situation you find yourself.

In Opal 1, we begin by introducing the word, metacognition, and the concept that defines it within the context of reading. A focus on metacognition supports young children to develop their understanding that reading is meaning making.

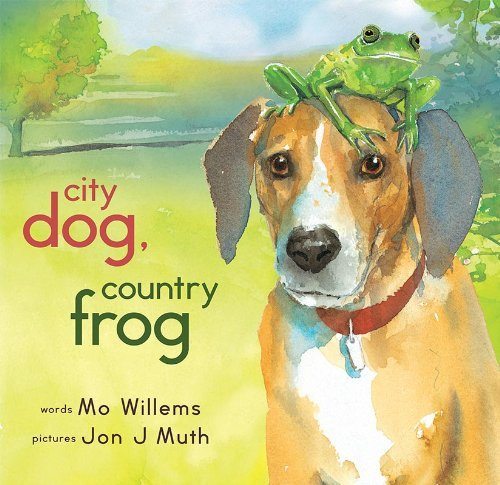

We began this “metacognition” work in Opal 1 this year by asking the children to "listen" to what was happening in their minds as Kerry read “City Dog, Country Frog” by Mo Willems aloud. As we read the story we asked the children to think about what they did understand in the story and also what they didn’t understand. This awareness is an important first step in the comprehension work we will continue to support as the children learn and grow as readers this year, and throughout their Opal School experience.

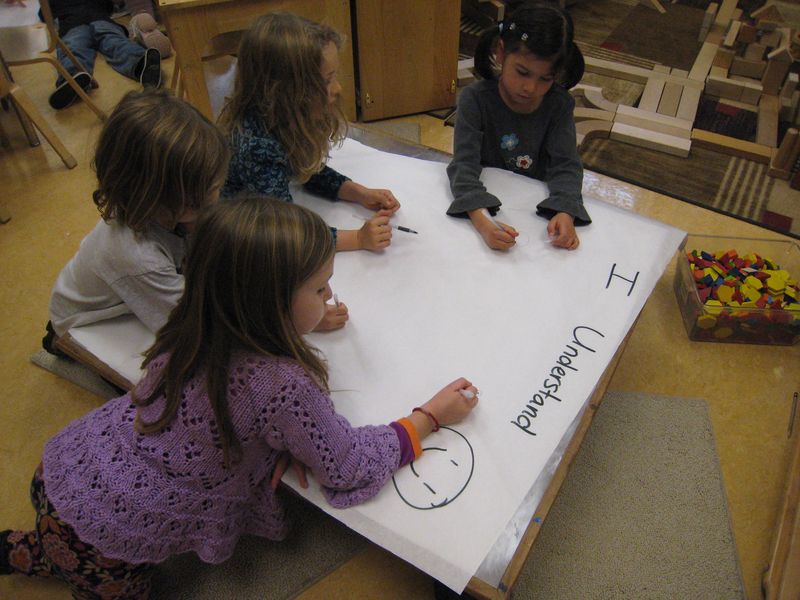

The children worked on large posters, drawing and writing their collective points of understanding and misunderstanding.

Here are some of the things they noticed their minds were thinking as they heard the story:

Sophia: I understand when the frog said, “I’m looking for a friend” then on the second page they were friends because they were actually playing.

Pearl: I understand that the dog was sad when the frog left.

Victoria: I understand that they made friends.

Aoife: I don't understand why frog was looking for a friend.

Maliya: I don't understand what happens in between the seasons.

Kennedy: I don't understand why frog is missing.

Malakai: I don't understand why the frog said, “but you’ll do” when he said "I’m waiting for a friend" when the dog was right there.

This experience opened the door for the secondary point we want the children to understand– that readers bring their own schema to a text. Schema is the collection of interpretations we have made of our experiences. It is everything we think we know and remember of our lives. When a child pointed out that something had been understood that wasn't written explicitly in the text, we were able to ask more questions and find out how they knew. When Bodhi said, "I understand that the frog hibernated," we were able to ask him how he understood that. Willems hadn't included that information in the text– just that during winter the frog wasn't there. Why had Bodhi understood this when other children hadn't? He let us know that he'd recently learned about frogs hibernating during the winter. He brought this schema to the text and it helped him understand something that had been a confusion to others.

Understanding the role of schema is a critical skill for proficient reading and a concept the children will explore throughout their years at Opal. It is also a critical skill for living in a diverse community. As children grow older at Opal, their understanding of schema will grow to include an understanding of perspective and will apply to their studies of community and conflicts in history.