Playing with History

It

is a widely held belief that play is the work of young children. I think this

statement has evolved because, as a society, we intend to give importance to the creative flow and joyful activity

that children so naturally engage in as they move through the earliest stages

of life.

Play

is so indispensable to human development that it has even been recognized by

the United Nations as a basic human need and right for every child.

Here

is a description from Richard Lewis’ book, Living By Wonder, that

might bring back some memories:

It was one of those warm summer evenings. I was on my way home when, just at the

entrance of the park where I had been sitting, I saw three small children

chasing fireflies. It was getting

late, but I lingered for a moment to watch them. The children were completely involved with what they were

doing: the sweep of their arms as

they tried to close their hands on a firefly’s humming light; their bodies

arching forward when what escaped them suddenly appeared a few feet away; their

excited whispers sifting quietly around us. Then quite unexpectedly, one of the

children, sure that she had caught a firefly, came running to her father

nearby– and opening her hand, proudly showed him what was inside. Both she and

her father looked, but there was nothing except her bare hand. No matter, off

she quickly went to her friends, dizzying themselves in their leaps and

hoverings, trying to find out what it must feel like to have particles of light

so close to them.

Think

back for a moment to your own childhood.

Remember the thrill of bringing your body up to it’s top speed, running

down the sidewalk, rolling down a hill, the anticipation and challenge of those

three little phrases: On your

mark, get set… GO!

Or

maybe there was a quiet place– a fort of pillows in your living room, the

highest branch of the tallest tree you could climb, the fleeting moment of

wiggling creatures in their world under the rock you overturn.

Remember your

favorite doll, your imaginary friends, the worlds you created with the magic

words: How ‘bout you be the… and

I’ll be the… and let’s pretend.

You could be anything you wanted to be, wondered about, worried about,

or wanted to try.

At Portland Children's Museum, we think these

words embody the spirit and experience of play:

joy, inquiry,

inspiration, listening and relationships, divergent thinking, imagination,

multiple forms of human expression, opportunities to find your medium, a sense

of belonging

Are there words you would add to the list?

At the Portland

Children’s Museum, we’ve been asking ourselves:

What benefits come

of childhoods steeped in healthy amounts of play?

And at Opal

School, we’ve been asking:

How can we put the power of play to work in the

service of the learning we want children to do?

The importance of

play is a pretty hot topic these days. Neuroscientists and other specialists

in human growth and development are finding important links between play, brain

development, and learning.

The American

Academy of Pediatrics is clear about the strong relationship between play and

healthy child development. We know that play evolved in our species so that we

could encounter novel things in the environment and figure out how they work.

We know there is a strong correlation between play behavior and cognitive

function: the fewer instinctive behaviors a species has, the more play

behaviors it has. Play literally sculpts the human brain: we know that what

“fires together, wires together”. Play behaviors invite rich experience and

robust thinking. And we know that children can learn a skill through direct

instruction or through play, but those who learn through play have higher

levels of engagement and the learning lasts longer. Children learn best when

skills are learned in meaningful contexts. Play gives learning meaning.

Because we believe

this research to be the best to which our culture currently has access, at Opal

School we’ve been wondering:

How might we use

the power of play to strengthen and deepen learning in traditional academic

areas?

In spite of all we

know about the importance of play for developing minds, we notice this widening

gap in our society between what we accept as places for play, and what we think

of as environments for learning. In

his book Play, Stuart Brown writes about current education models:

The neuroscience of

play has shown that this is the wrong approach, especially considering that

students today will face work that requires much more initiative and creativity

than the rote work this educational approach was designed to prepare them for. In a sense, they are being prepared for twentieth-century work, assembly-line

work, in which workers don’t have to be creative or smart– they just have to

be able to put their assigned bolt in the assigned hole.

If play is the

engine of learning, if play sculpts the brain, then how can we capitalize on

the power of play to make learning even more real and meaningful—in schools, in

museums where children are an intended audience, and in parent/child

interactions?

Supporting play

brings great joy in the moments we spend with children now, and can help us be

certain that we are offering them the kinds of experiences that are stuff of

happy childhoods. But we must also

be asking ourselves about the work we are doing in the service of preparing

citizens who can participate fully in our democracy as creative problem solvers

and strong, critical thinkers. How might play and playful inquiry help with

that?

We seem to stumble

when it comes to figuring out how to participate and support this genius of

childhood as adults who feel responsible for somehow “teaching” children a

bucket of information we believe it is vitally important for them to know—the

facts of early American history, for instance.

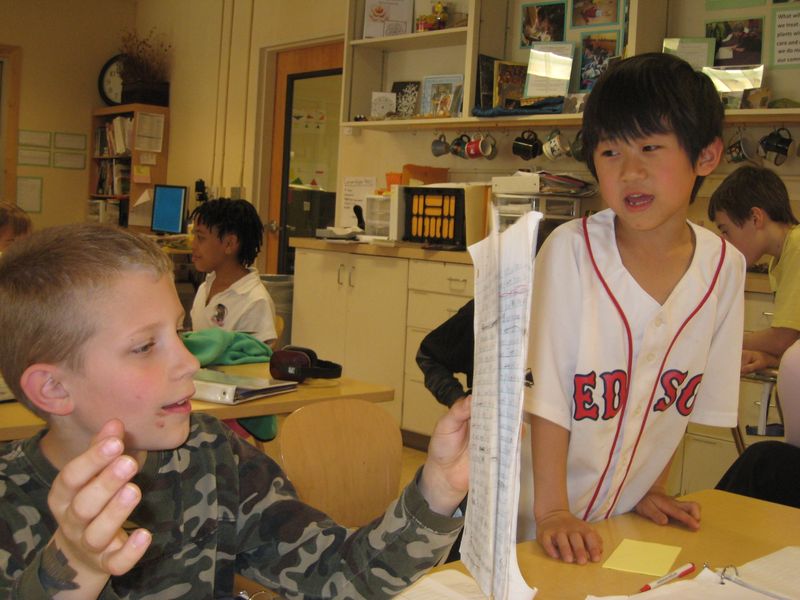

Susan Harris MacKay tells a story about playful inquiry in the classroom:

I’m going to tell you about an experience I had with my class of 9 –

11 year olds at Opal School as we approached the Oregon 5th Grade

Standards for teaching American History. This will be just a small slice of a

project that lasted over 6 months and intersected every aspect of our lives in

the classroom.

We began, early in

the year, with a homework project intended to help us build a collaborative

timeline of the decades of the American story beginning 1770 – just before the

time of Revolution and Constitution – where the Standards dictate we focus our

attention.

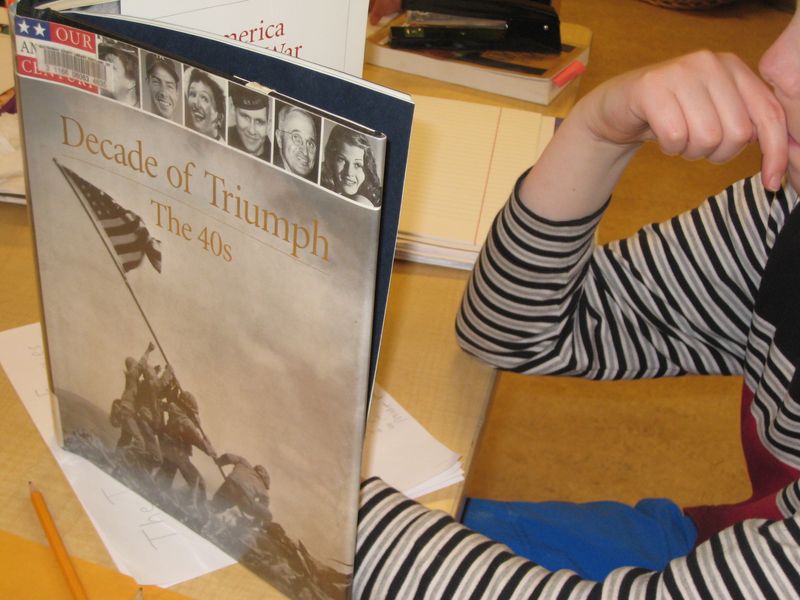

In order to begin, I wrote the years on small pieces of paper and asked each child to pull one from

a basket – playfully beginning 6 weeks of research to be conducted at home and

shared at school. Each week they were asked to research different aspects of

their decade – elections, census questions, art and music, big questions and

conflicts of the day.

The intention was

for this to be a foundation for work we would do together. It was hard for me

to imagine that such a vast scope of the American History timeline would

provide much meaning or engagement for 10-year-olds, just a decade old

themselves. I thought that this timeline would provide a backdrop and context

for other work as we returned to the early part of the timeline, as dictated by

the Standards.

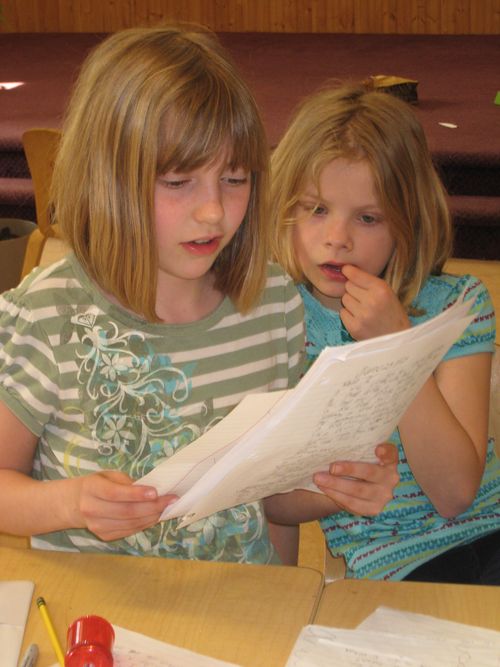

But as kids

learned more and brought more information about their decades to each other,

their interest grew.

Between the

independent work they owned and

the sharing that spiraled because of it, a playful exchange developed between students – connecting what they’d found out and finding a sense of

belonging because they each held such an important piece of the whole.

Their research

involved play with the arts and materials, and, of course, they played with

each other—so I shouldn’t have been surprised, I guess, when I started to hear

their ideas about moving forward with this project come together in a way I

hadn’t imagined.

In his book about

play, Stuart Brown writes that the opposite of play isn’t work—it’s depression.

To be sure, these kids were working hard and the more they worked, and the more

they shared, the more curious and invested they became and the more ideas they

had!

First they

proposed the idea to write historical fiction that would feature a 10-year-old

character who lived during the decade they had researched. (That is a story in itself and one I won't focus on in this article… but suffice it to say, they amazed me!)

Then they

wanted to become the character they’d worked so hard to create.

Then they

wanted to meet each other in character.

Every idea came through them with delight, excitement, and anticipation of possibility. This was their

play – and I chose to listen their desires to move forward. My agenda followed

theirs. And for that reason, this project can never be repeated.

Real

play … emerges from the imaginative force within. …with a pinch of pleasure, it

integrates our deep physiological, emotional, and cognitive capacities. And

quite without knowing it, we grow.

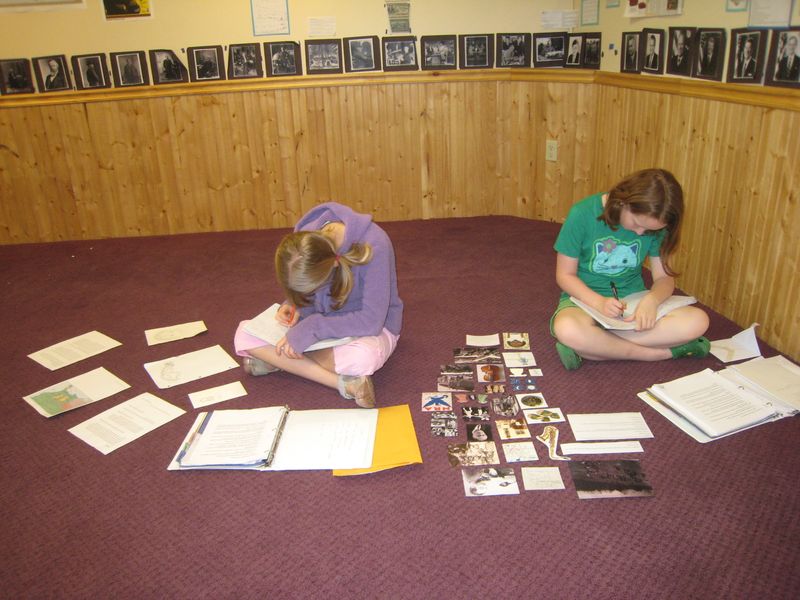

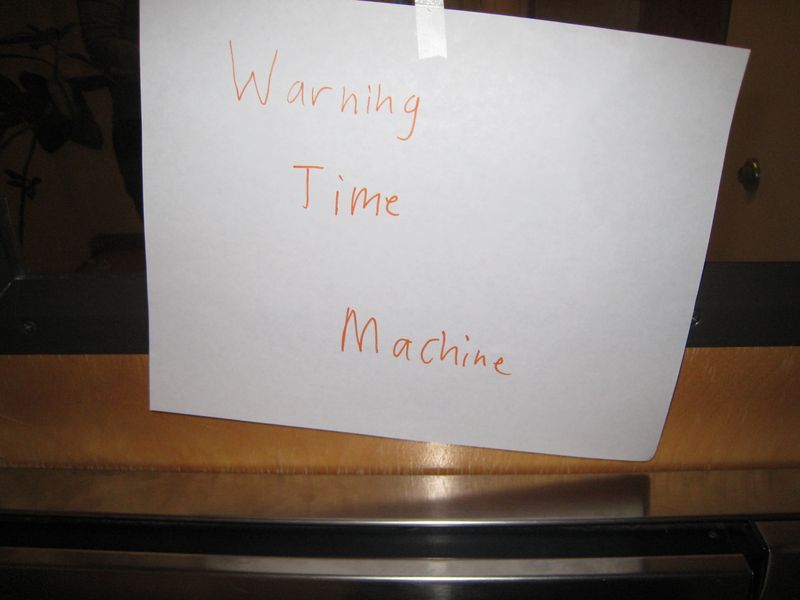

Of course, if they

wanted to meet in character, they would need a time machine, which was a simple

matter of imagination. The first meetings of characters were all about

play—playing together in character, meeting each other, finding out what would

happen, acting out possibilities, and especially, getting their giggles out.

The more we

playful we are, the more we want to engage and think and share and they each

brought so much to each other from their research and the perspective they’d

developed. They were fully living in the skin of the decade they’d imagined

through real research.

Here are a couple

of reflections written by students after that first trip through time:

It was so cool seeing other people in different clothes or

how some kids tried to act. Cash was the most funniest character. He was a

hippie– and he was a good hippie.

Jared, age 10

Yesterday, when we climbed into the body of our character

was probably the most fun I have had this whole school year. The way that

everybody was able to “leave themselves” at the year 2009 just completely

worked. Everybody has worked so hard to learn everything they possibly can

about their decade and that really showed and paid off. I felt that it went

really well and was really fun when we went outside because a lot of the

characters had never even heard of a playground!Sophie, age 10

My

agenda, and the agenda of the state of Oregon still mattered. Kids still needed

to learn the content the standards required. The engagement of the children in

the project left them ripe for direct instruction. Imagine a group of perfectly normal 4th

and 5th graders hanging on every word of a lecture about the Bill of Rights! For an hour! But they needed this information in order to breathe ever more life into their imagined worlds. Their brains were primed to connect, and

so they absorbed it willingly and put it to use.

Now that they had

a time machine anyway, we wondered: What if these characters could convene and attend

the Constitutional Convention? What would these children of the future have to

share with the Framers of our government?

I want to share a

few snippets of the speeches they wrote to share their experiences and

perspectives at that Constitutional Convention. Consider the

rigorous task put before them – the research, the writing, the development of a

character’s voice through which to deliver an imagined perspective. Here is a

sampling of the depth and range of this excellent work:

Isaac 1770:

I have grown up in a nation that has been recently created for the purposes of

liberty, justice, freedom and independence, also known as the States of America.

Everybody after my time has been talking of a constitution of these states,

that they say shall be united, but how could the states be united?

Here is Julianna's speech in it's entirety:

Download JuliannaSpeech6.17.09.mov (14663.0K) (Use your browser's back button to return to this article after viewing the video.)

Max 1820:

If everyone was equal no one would be scared. The angry wild fire in a white

man’s heart would be put out by cool waves of water. The shards of hatred

disgust, fear, lies, and stories would break. White men would finally be able

to see again and everyone would be safe.

Here is Josephine's speech in it's entirety:

Download JosephinedecadeSpeech6.17.09.mov (8947.3K) (Use your browser's back button to return to this article after viewing the video.)

Jaden 1910:

The government has looked at the Constitution sideways. They believe that

children, women and blacks are simply property. Like a chair in your house,

nothing more. I have traveled on a terrible boat ride thinking I was going to

the land of hope but now this land is not the land of hope. The Constitution

lied. It did not fulfill its duties. It did not give a better life or liberty

or justice for all. So now it’s time for the people to act for the common good.

Benjamin 1970:

I stand here knowing I can make a difference in this world. Discrimination is

the first thing I would change. The Constitution says “every man is equal”, but

my father is a man, and he can not drink from a clean fountain. He cannot sit

on the front row of the bleachers and watch me wrestle.

Emmerson 1990:

Education is the key to peace, for peace is not just no war, it is no violent

acts for peace. Because every time a bullet flies, a young mind is broken apart

by fear, by fear of losing something –something he can grasp to hold onto in

the dark. If you look at any time in history, any place in the world, you can

see families being torn into the rainy tornado of war. This tornado has torn

apart my family and many others. To feel empathy for anyone you must look at

two sides of things even though one side is hidden to you. To decide one side

is not important is a gigantic mistake.

Is it possible

that, ironically, the more we play, the more rigorous the curriculum can be?

The higher expectations for thinking and problem solving and innovation we can

have? Is it possible that play rasies our expectations for those important 21st century skills?

Ultimately, the

biggest task I put before them was to think together with the constitutional

writers (played by me, a parent, and a co-teacher) about language that could be

included that would have made fairness and liberty and equality more clearly

required for all citizens.

Click to this post to see snippets of the "Convention" in action.

In their speeches,

many of them had appealed for the use of the heart in law-making and law

interpreting. I told them about the contemporary discussion about President

Obama’s Supreme Court nomination of Sonia Sotomayor and the concern of some

that she spoke openly of the need for empathy in law. I asked them what they

thought about that.

John: It shouldn’t all be about what you feel. It has to be

about what agreements we’ve made in this country—not, “Well, I feel this person

who did something bad is sad, so I’m going to help him, not this guy who really

has safety because the law says." It is about what laws we have in America.

Period.William: If the laws are correct and your heart is correct, your

heart and the laws should fit together. You should be able to act with your

mind according to your heart. You should be able to do both. Either there’s

something wrong with the law, or your heart is in the wrong place, and you have

to fix one of them.Jim: There is no wrong decision! There’s no such thing as a

wrong opinion!Lillian: There is such a thing as a wrong decision. But there’s no

such thing as a wrong opinion.Many children

agree.Lillian: Anybody can have their own opinion. Like I bet my opinion

is very different from anybody else’s here. It might be similar but it’s

different still. But if I make a decision to do something to someone, it could

be wrong.Anna: You don’t want to use your heart so much that you are just

saying “I don’t like this guy so I’m not going to help him.” That’s using your

heart in the wrong way. It would be the wrong decision but you could have that

opinion. Your opinions can be different than your decisions, and they kind of

should be.Margaret: I think this is really just another reason why we should

learn history. Because if we make a decision that in history lead to horrible

things that we had to fight over, then we should think about history—especially

if you’re in the government, you really need to know about history so you know

not to make a wrong choice.

They continued talking, and at another point, I asked them:

What is the role of empathy in making laws?

Margaret: I think the role of empathy is to really feel out what

other people would feel before you make a decision that affects them. Like FDR was really good at feeling out

how poor people felt during the depression. He made laws according to how other

people felt other than him.The United States

is really a big web. If a leader does something that affects one group of

people, the web can break, because they’re part of our community, too. If that

person doesn’t think about other people, everyone suffers in the smallest of

ways.Jim: If you think all you should use is empathy for your

decisions, maybe you think that, but you cant’ quite do that when you have

opinions. If your opinion is that using empathy is the only way to make

choices, you can’t quite use your own opinions to make decisions because there

are two opinions out there.Teacher: I’m wondering if it’s when you don’t make decisions with

empathy that you end up taking sides?Margaret: Yeah, you can’t really make a good decision without

empathy. It requires you to think of everyone’s perspective.John: It’s like there are two doors and they both lead to hallways

and one has treasure in it and that’s good for you and only you. The other hallway has people who are

stuck in it and they can’t get out but if you let them out they’ll be

free. But you can only open one

door. So the empathic decision would be to find a 3rd door.

I was stunned.

To find a third door is such an elegant idea. It occurred to me that that was

perhaps what this whole project was about. Perhaps what playful inquiry is all

about: finding new possibilities we simply haven’t yet imagined, but that exist

just as surely as another door to open and inviting us through.

In the end,

this is the language they decided to include in their revisions to the

constitution:

When there are sides that are not in agreement, make a

compromise that will make all sides happy enough to avoid conflict.

The simplicity of their final language is

profound. In the end, they related much of their thinking to what has worked

for them as they’ve developed their own classroom community all year

long—finding parallels between their public and private lives that will help

them navigate their experiences as citizens in this society for the rest of

their days.

Some might wonder if it isn’t a little sad

to have children learn about these stories of struggle and conflict and

violence that we have in our history as a country.

These children were serious and contemplative,

but not sad. They were playing and working and so they were not depressed. This work was heavy and important – and

they knew without a doubt that it had everything to do with them.

Children are caught in this incredibly

tricky place. Their drive to learn and their drive to belong are equally

strong. In their work with adults, they so often find the need to compromise

one or the other of these drives. Too often, adults distrust the drive to learn, and threaten

children’s need to belong by taking away the right to play and alienating,

shaming, or punishing those who don’t perform.

What might happen for all of us if we

unleashed the power of children’s minds by creating learning environments that

supported playful inquiry?

These reflections of the work the children

did together offer a glimpse of possibilities:

The children of the future

need stories to wonder and learn so that they can be curious. And if you’re

curious, you don’t make stereotypes and when you don’t make stereotypes, you

don’t discriminate against other people. Which is good. Because discrimination

doesn’t make us a happy community.Chloe, age 11

When people look at the things I have created to tell

stories, I want them to think about who they could tell those stories to. And I

want these stories to sing in their hearts.Olive, age 11

The last line

of Stuart Brown’s book echoes these ideas:

When

enough people raise play to the status it deserves in our lives, we will find

the world a better place.

But I like the

way this Opal 3 student said it even better:

The children of the future should know this history because

if they don’t, how will they know how to hope? They need to know that you need

to have belief and strength to be able to make the world a better place.Max,

age 11

As the current 5th grade teacher at Opal School, I am so inspired to read this post in its entirety, to see the possibility of a whole project coming out of time carved out for children to play. When I go back to the top of this post where you asked what words I would add to the spirit and experience of play, I want to add: the feeling of getting lost in time and space while you play. What a great connection to a study of history! When a teacher learns to trust that play will lead to rich experiences, nurtures a community who knows how to play together and take risks together, and is willing to play herself… wow! They will ask for resources that will cover the state standards and then some, and, the learning will stay with them (and you!) forever.

When you asked if there are words that embody the spirit and experience of play you would add to the list, I would add the word natural. Much like learning is a natural instinct I also feel that play is natural. You don’t force play in a child; it is a natural part of childhood. Children innately what to play with things and explore! Children learn so much through play and the experiences that play unfolds. I feel that play should be incorporated into all grades of learning. Play opens up the window for you to discover the best way to learn something. What children learn through play cannot be taught in a text book, it’s too rich of an experience. Just look at this example of the playing with history and how rich of a learning experience those children had. It’s so refreshing to see a teacher let 5th graders play, and to see 5th graders get excited about play.

-CMSD

The words I would add to the list are challenge, focused and feeling fully alive – all of our senses are engaged and we are living fully in each moment.

Empowering our students to use play as a way to connect with any learning is very powerful. Play so intimately connect us to our culture, emotions, sense of identity, and understanding of others.

I think the emotional connections the Opal students made to their historical characters is what made this learning so powerful for them. Empathy is a vital attitude that all problem-solvers will need if we hope to solve any of the global problems faced by our world.

Kudos to the Opal teachers for supporting the natural tendencies of children to develop relationships – even fictional ones – to lead this inquiry.

As somebody who was able to participate in this project as both a parent and a “critical friend,” I appreciate revisiting it through these two entries. This outing negotiated some interesting tensions through playful historical inquiry and an emphasis on empathy. It’s the kind of investigation I wish more teachers of older children would explore!