Looking for Invention

With generous funding from The Lemelson Foundation, Opal School is embarking on an exciting journey this fall to research Invention Education alongside our friends and colleagues at Project Zero of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Ben Mardell and Mara Krechevsky. The task in front of us right now is to frame our research questions. We’ve begun in a place that we’ve come to trust to be our best source of information — the children themselves. For the first several weeks of school, Opal School teachers have been trying to capture and identify what looks to them like what might be the natural inventiveness of children. We assume children arrive at school with tremendous competencies. Why wouldn’t an inventiveness that leads to invention be among them?

On Wednesdays at Opal School, children are dismissed at noon so that the staff can work, share, plan and think together. We have designed our schedule to include time for these critical encounters and our families have found ways to support one another with this short day every week because they understand the quality of the program benefits immeasurably from this time. This week, teachers brought with them an image they had captured that they felt framed something that looked like invention. In small groups, made up of teachers from every grade level, each person shared what they had brought, the story it held, and their own thinking about what made it look like invention.

Here are a few samples:

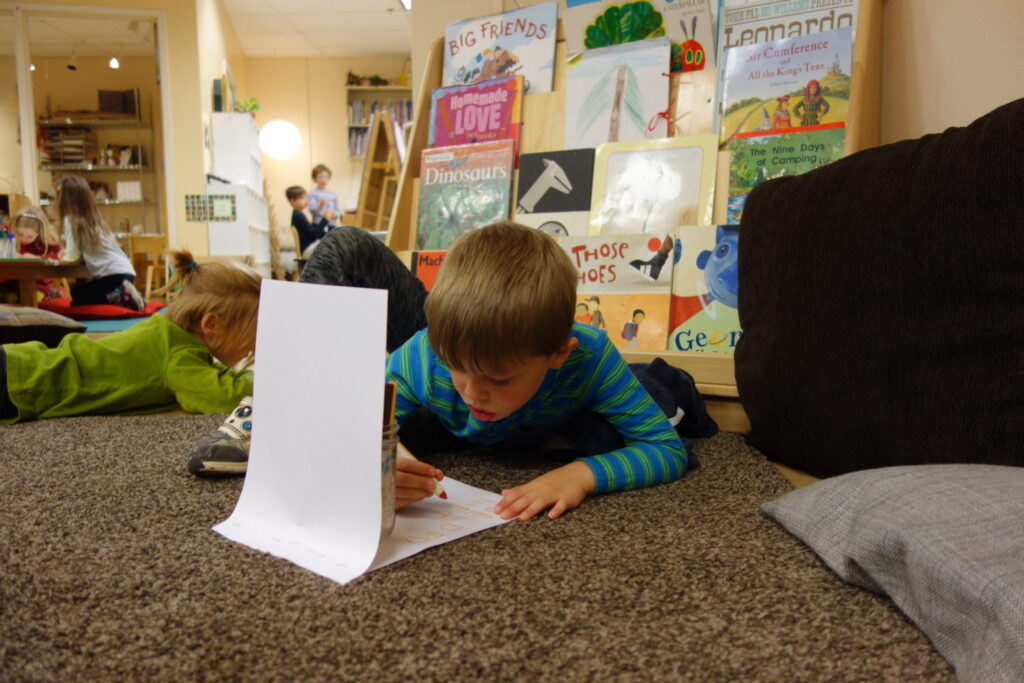

Lauren said that she had been looking for invention/inventiveness in ways that she maybe hadn’t seen before. Her capture of this child who had invented a way to move a page out of his way while he continued to write helped us consider the ways in which the choices a child has in the environment — choices including where to work, and what materials are available at any given time to work with — can support both problem-finding and problem-solving. If children have these choices, then perhaps they are encountering more problems than they would if they had fewer choices. Perhaps encountering those problems offers them more opportunity to exercise their inventiveness.

Nicole shared this image of children looking at a map together and told us that they had voiced a wish that the map had a better key and thought they could make one. This helped us consider the ways in which we offer children opportunity to explore content in a way that invites critique and action.

We discussed the relationship between inspiration and frustration.

We considered the ways in which we are saying to children through environment, materials and choice — “Go ahead, have a problem. Then fix it. You can have what you need.”

Chris brought this image to the group. While he said that he recognized that the child was following the directions of an experiment for which the outcome was known, she was still so clearly expressing surprise, delight, and engagement. We wondered about how these emotional qualities support invention. He said that what really fascinated him was that most of the children took off from this first experiment and spontaneously began to make their own — to work to discover more than they could from the first, by asking more of their own questions. We wondered whether these dispositions of surprise, wonder, and delight were prerequisite to sustained tinkering and experimentation — going beyond what is already known.

This led us to consider the ways in which we might be wired as a species to find not knowing pleasurable. If play is the strategy that evolved in our species to help us figure out what’s going on when we encounter the unfamiliar or the unknown, and play is pleasurable, then maybe it makes sense that we are designed to find not knowing fun. Chris connected us to an experience he’d had recently listening to an expert storyteller who had kept the audience on the edge of their seats by punctuating his story with songs in the places where the audience most wanted to know what was going to happen next. It was incredibly fun not knowing. We wondered together about the powerful connections between invention and narrative. To invent, you must be able to tell stories of future worlds and find new ways to do things there.

Cassie hadn’t brought an image from our beginning community, but she shared some of her curiosities about children inventing solutions as social problem-solvers. We agreed that the beginning school might be a really exciting place to observe the kind of invention children do when they are faced with social problems.

We thought about inventing language, inventing strategies, and inventing ideas.

We wondered about the relationship between constructivist theory and invention.

And from these conversations, some of our initial questions begin to form:

- In what ways and when are we saying ‘yes’ to invention? And when are we not?

- What qualities seem to support inventiveness?

- What is the relationship between play and invention in the elementary school classroom?

- When does inventiveness or creativity lead to invention?

- What is foundational in an environment that supports invention in the elementary years?

What questions do you have? What are you observing in your practice?

So excited about this thinking and that this is just the beginning of cracking open these concepts. I look forward to reflecting on what you shared here and beginning to hone in on the multimodal and multifaceted world of invention.

Some key takeaways for me:

– invention includes encountering problems

– critique & action

– inspiration / frustration

– problem / solution

– how emotional qualities support invention (surprise, delight, engagement, other qualities?) >> leads to sustained experimentation

(lifelong learning?)

– powerful connections between invention & narrative/storytelling and the power & pleasure of the unknown

– invention as social problem solving