Listening for What’s Next, a math exploration

There are hundreds of different images of the child. Each one of you has inside yourself an image of hte child that directs you as you begin to relate to a child. This theory within you pushes you to behave in certain ways; it orients you as you talk to the child, listen to the child, observe the child." - Loris Malaguzzi

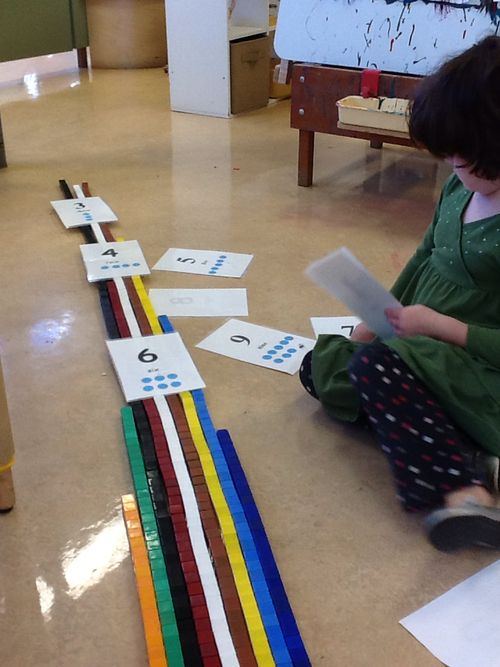

At the beginning of the year we always begin math by offering time and space for the children to explore a variety of math materials. Besides wanting the children to become familiar with materials they will be working with later on, we are always curious to see how they choose to work with these materials, what they are bringing to the equation. This year, a lot of excitement centered around the unifix cubes. As often happens, the students began to work together almost immediately to make a long, long, long train of cubes. As the train grew, so did the excitement with more and more students coming over to see and help with the work. There is something about making something so, so long that really tickles their brains.

In a classroom full with tables and materials, the lines can only be straight for so long. These children turned the line and it started to curve around the block area and past the message area. Our day was over. it was time to go home. Usually work on the floor around the classroom gets cleaned up. This time, we told the kids to leave it on the floor – the energy and cooperation they were showing felt strong and exciting, and the work seemed important to them. We decided to leave it till morning and see what would happen when they came in.

The environment you construct around you and the children also reflects this iimage you have about hte child. There's a difference between the environment that you are able to build based on a preconceived image of the child and the environment that you can build that is based on the child you see in front of you — the relationship you build with the child, the games you play. An environment that grows out of your relationship with the child is unique and fluid. – Loris Malaguzzi

When O.L. came in the next morning, he exclaimed, "This is the best thing yet! We are getting it to go all the way around!" Many students went right back to work. As they worked, they noticed the train was breaking a lot. This was not discouraging, their motivation to build it together was such that a problem was simply a chance for reflection, and an oportunity to come up with a creative solution.

Teacher: Why is it breaking?

KK: Because it is too long. When it got too long you have to bend it and then it breaks.

LS: Yeah, that's exactly right. And, when it goes over this little bump.

OR: We're making a bridge because this one is too high to connect so we are making it go up.

KK: It is harder than we thought it would be.

LS: I fixed it! All I needed was to take two out!

The students working on the train were in an optimal state of mind for learning — where the risk is low for the children, but the challenge is high. In this case the challenge included working with many other people who they were getting to know, sharing ideas and bringing those ideas together, working with a new material to see what it could do, and solving problems that came up.

I wanted to encourage their curiosity and innovation and offer them another opportunity to continue exploring. Based on their wonderings about why the line broke and the need to curve the train, I wondered what would happen in a different space, a space not so crowded or with so many obstacles. Knowing the museum is closed on Mondays, we planned to bring a group out into the hallway with a big bin of unifix cubes and see what would happen. This back and forth exchange of ideas and possibilities with the children is something we refer to as a ball toss (an idea that came to us from Loris Malaguzzi the founder of the early childhood schools in Reggio Emilia). If we listen carefully enough to the children with our ears, but also with our eyes and even our hearts, we can see what they are wondering or asking or what materials or next step might spark them to investigate further.

In the hallway, the group of children spent some time initially just looking at the space. The students noticed the stairs going up, they noticed that the hall was like a long line with curves at the end around the water fountain. Then they noticed the curve at the other end of the hallway and I offered, do you want to go look over there and see what that is like? When they saw how long and straight it was, cheers went up. They all knew right away that they wanted to build a train here in this very long straight hallway and they got started right away.

ET: Let's make a REALLY long line. This line is getting very long, isn't it?

OL.: we're almost there, almost.

OR: It's turning back. Oh, it's turning.

ET: look at this long, long thing. This is gonna be a big, long trail.

Teacher: is it going to be the same as the one in the classroom?

LS: Longer, it's already longer.

OL.: it's the longest thing yet!

ET: If we stood it up it would fall very quick.

OL: it'd be sticking out of the roof.

LS: I can picture it in my brain.

ET: I can picture it shining in the sun. It would go all the way to the moon.

OL: The moon is in space. It's not that tall, it's not really that tall.

LS: It's longer than a school bus.

Teacher: What should we call it?

OR: Snakey

OL: because it is Snakey, curvy.

E: A very long river.

OR begins to walk the line, counting as he goes. He is spontaneously measuring with his steps.

LS: also goes to the beginning and counts his steps, measuring the line.

VD-B noticing that the number of trains keeps getting smaller as the trains grow and grow.