Leaning in, Plunging Deeper: Going beyond Reading

I recently came across the following passage in The Sun:

The less you are caught up in your own hopes and fears, the more you can see suffering straightforwardly. Accountability here means being honest, incredibly honest. You see that harm is being done: you see someone harming a child, an animal, another being. You see that clearly, and you wish to lessen that suffering. Then the question becomes one of how to proceed so that the person you see as the problem becomes accountable, willing to acknowledge what he or she is doing.

You realize how hard it is for you to acknowledge what harm you are doing in your own life. Seeing how much it takes to become accountable yourself, you try to find skillful means to communicate with this person so that barriers come down, rather than get reinforced. It has everything to do with communication: How can you each hear what the other is saying?

“Beyond Right or Wrong,” Pema Chödrön, in conversation with bell hooks, June, 1997

When I first read these words, I thought, “Yes! That is what we are trying to do in the Willow Community this year!” My first instinct was to bring the piece to the classroom the very next day. I pictured us reading and unpacking these important words together, finding value in them, making connections between these ideas and the work we had already done, and thinking about how we could continue applying those words. In the picture in my mind, students would connect with the piece, seeing the merits of these words, and feel good about themselves and their ability to talk about these complex ideas. As I projected how our work would go, there was a secureness in my vision; the sense that it would feel safe to sit together and talk about this piece.

As I continued thinking, however, I realized that by offering an explanation of what I hoped we would figure out, I was essentially denying the children the opportunity to construct these ideas and values for themselves. Furthermore, I might be sending the message that I did not believe they could construct them. The more I reflected on my initial ideas for this text, the more I leaned away from them. We know enough about how people learn to realize there is much greater potential for learning when we create conditions for learning rather than merely telling or informing; when we allow the opportunity for emotional connection and involvement; when there is room for disequilibrium and dissonance. In my first vision of using the piece, there was a sense of feeling good and feeling safe, but now when I think about the depth and complexity of Chodron’s words, I realize that it might take more than sitting around a circle talking. It might take experiencing feelings other than feeling good to construct a deeper understanding of these ideas and, even more, how to practice them. We would have to actually experience what it’s like to be accountable for- and to- ourselves and to communicate in a way that we could hear what the other is saying. This is hard, hard work that in the moment might not feel so good, but might lead to something so much better – we might be able to communicate about hard topics that in a way that would help “barriers come down, rather than be reinforced.”

To me, as a perennial avoider of conflict who often finds communicating extremely difficult, I am now even more aware of the limitations of only reading an inspiring piece. There is certainly value in bringing inspiring texts to a classroom community, but I am reminded that that is only one part. Now, that part feels like a starting point, a challenge, perhaps even something of a roadmap. With that in mind, I started looking for opportunities for us to live by these words even before we read them together.

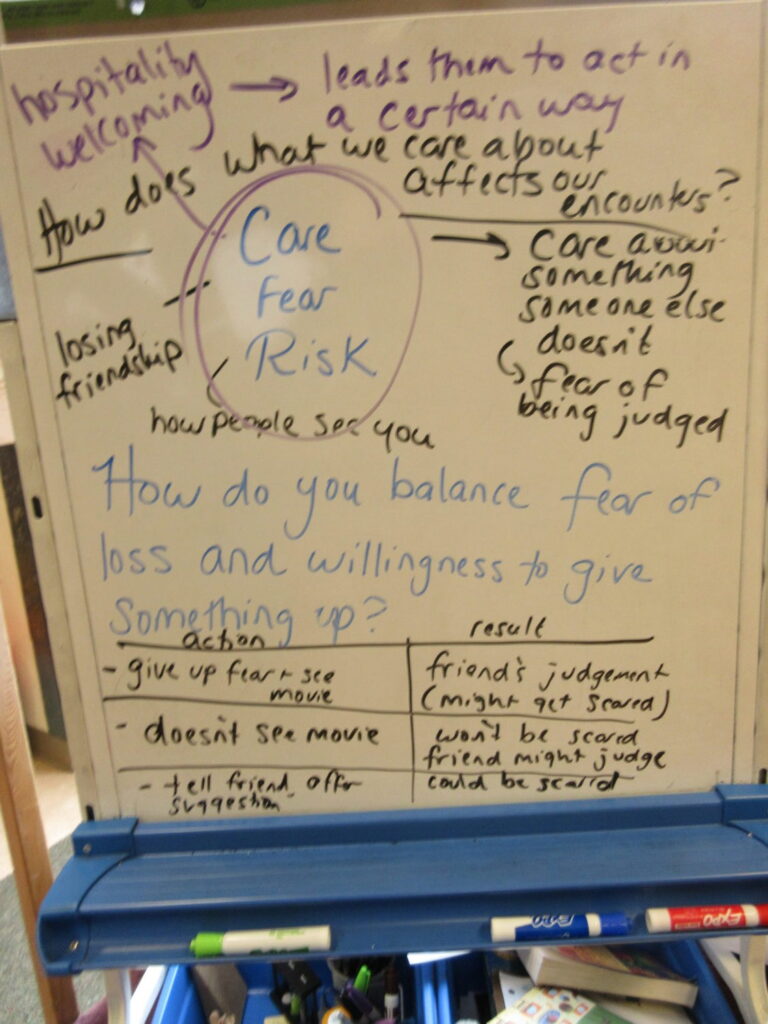

Around the time that I encountered the passage above, the Willow community of fourth- and fifth-graders had been talking about care, fear, and risk. I thought there might be a connection between the relationships between care, fear, and risk, and the way Chödrön is encouraging us to communicate and act. When we unpacked care, fear, and risk, students could see beyond the surface level of someone’s words or actions to find what they really cared about or were afraid of underneath. This gave us deeper understanding of – and empathy for – what was really going on for people in our community.

For example, when Alex and Louisa were paired to use materials (thick sharpies) to represent the two different perspectives of two historical groups, they started out exchanging ideas and sketching possibilities.

But then, an immobilizing shift happened. Suddenly, they looked like they were not getting along or getting anything done. Alex sat motionless, staring into space. Louisa took the paper away and started agitatedly working by herself in another spot. However, when we brought them together to find out what they cared about, what they felt was at stake, and what they worried about, a different picture appeared.

Louisa: I felt like my idea was going to get swept away. Like we couldn’t do it anymore.

Teacher: Alex, did you have a worry too?

Alex: I guess I was frustrated with the markers. I couldn’t draw as well as I usually can with these thick markers.

Teacher: I know you really see yourself as someone who can draw well. I wonder if you were worried about that image people have of you changing if you couldn’t draw as well as you wanted to with this material.

Alex: Yeah.

Teacher: Did you hear Louisa’s worry, too? Do you have a response for her?

Alex: We can do your idea too.

We brought the experience back to the class as a story for everyone to reflect on and learn from. Alex and Louisa talked easily and readily about what happened when they could look through the lens of care, fear, and risk, which was so different from the tension they felt in their moment of challenge in which they were focusing on their fears. We brainstormed other fears, cares, and risks that might come up when working together:

Cooper: I could worry that the other person would not like my idea, or would always reject my idea – that would be hurtful – or would criticize how I felt.

Jasmine: Maybe people are afraid of not having their idea. Maybe if I says yes to Jackson’s idea then we can’t do my idea, so what if I just say no? I like my idea, because it is better, in my perspective, so then I would just say no, so their idea won’t be a possibility. Because I am afraid if I say yes, then they will have their idea and mine would not be shared.Maylin: If I was the other person, I would consider saying no to her idea because she said no to mine… and then we would get into an argument about whose idea is better.Jasmine: If I have to do a drawing, I can stay in my comfort zone if I don’t do it at all. This way, I don’t have to mess up.

Alex: There is always a possibility to not get it right.Oceanna: It makes me think about a pencil and a pen. If you don’t want to mess up you go in pencil first and if you do you can take it back… sometimes it is harder because if you care about your idea, but you are afraid that someone will jump over and change your idea… You can’t erase a pen and when it goes out there and you can’t take it back.

A few days later, I invited the students to design skits that further explored these ideas of care, fear, and risk. Students worked in small groups to design and perform skits – one of their favorite means of exploring complex ideas. They crafted stories in which the audience could see how what the characters cared about influenced how they acted, which gave us a lens into their inside story of care, fear, and risk.

Though the characters and scenarios in the skits were made up, I do believe that playing with, performing, and saying these words and ideas out loud helps us become more comfortable and able to try to use these habits of mind of seeking understanding of others’ perspectives and experiences and of communicating our thinking and feelings- which is hard, hard work that can be scary, but is so necessary. As Oceanna said after we reflected on the experience with the skits, “all fear is usually because you care about something.”

I am still looking for more ways for us to “each hear what the other is saying” in a way that we can become accountable to ourselves and to “try to find skillful means to communicate with this person so that barriers come down, rather than get reinforced.” As we study stories of history and the stories that unfold right in front of us, I am confident that we will find plenty of opportunities for this kind of work in ways that are even more meaningful and impactful than talking about a moving and eloquent piece of writing. I also think that I will eventually bring that piece to the Willow community when they are ready to find themselves in the words, having had experience with these concepts already.

What about you? What experiences do you lean into and lean away from? Why do you think that might be?