Considering Risks and Opportunities

I’m interested in the ways in which these strange days of learning about teaching during a global pandemic serve as a kind of sieve, shaking loose the things we didn’t know we didn’t need and leaving behind the stuff we can’t do school without – exposed in ways it has not been before. Teachers are now guests in other people’s home, every day, a voice and presence mostly uninvited and, to only varying degrees, welcome. Parents are eavesdropping and remembering their own experiences in school with teachers. I wonder what feelings are returning to them as they listen to teachers teach their children. I wonder if things are familiar to them – if this stuff we think we can’t do school without has changed in any way, or what has stayed the same.

We are learning not only what we can’t do school without, but what we can’t do without school. So masked children arrive to school buildings where they meet masked teachers in forward facing bubbles. Where once school was a place to learn to share, now it is a place to learn that sharing can make you sick. It can make your family sick. People are dying from sharing, from hugging, from singing, from smiling with their whole faces. What else are children learning, particularly here in the United States, as we hold them in these containers on behalf of the economy and bear the weight of a failed response to a national crisis?

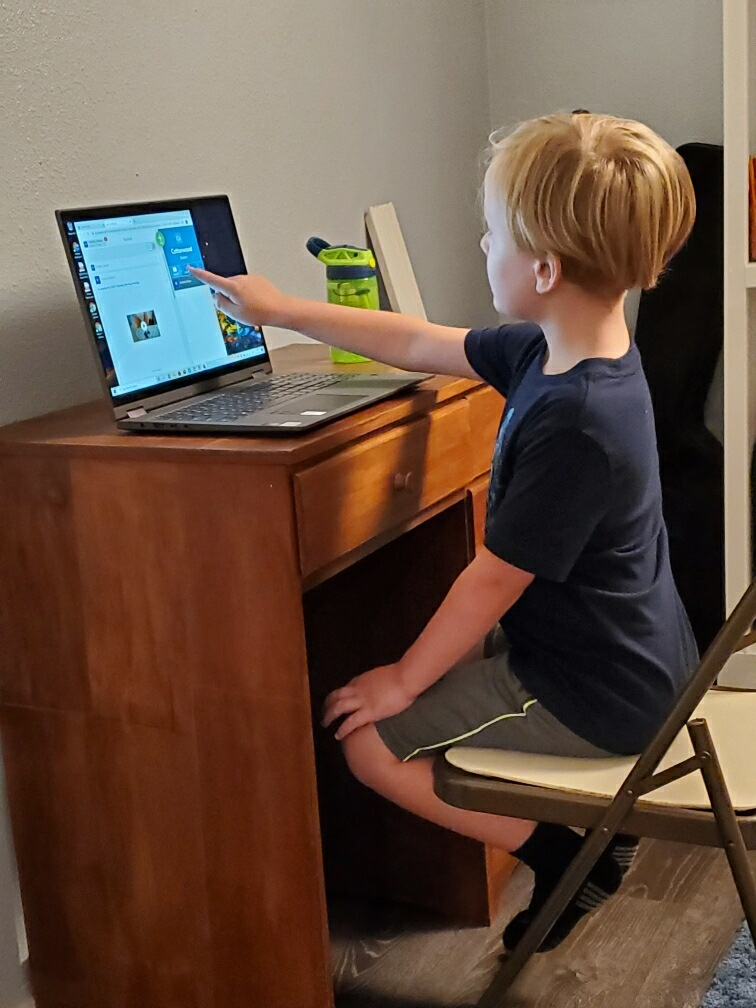

I think about the experiences I learned about this week. In one case, a small group of 5 year-olds were asked to count the disappearing squares as they said good-bye at the end of their online math session. One child figured out how to log off and then jump back on. And then other children did the same. So for a time, children were popping on and off and the teacher laughed with them, enjoying the game and the prolonged engagement with addition and subtraction until she said she had another meeting so they all really had to go, and they did. In another case, a 7 year-old and his mom were first to arrive in class and happened to share a quick story with the teacher. The child had a theory about the thick smoke around us and the pandemic which were both keeping us inside. The teacher, who had other plans, of course, saw the opportunity for rich discussion with the whole group and asked this child if he wanted to share his theory with others. He did. So their session became a lively, playful engagement with “what if” thinking and a chance to talk with each other – in a way they invented themselves — about the hard and confusing things we’re all living through right now. The teacher’s plans were saved for another day.

In these moments, the parents I spoke to were surprised. They paused and considered the dissonance between what they expected school to be, and what it was. They were surprised that teachers were willing to make split second changes to their own plans. They were surprised about the ways children found to play together and that teachers laughed with them and that the children stayed engaged.

In another case, teachers, facing twenty-five 7 year-olds on Zoom, played videos of reading instruction for children to watch while they watched the state of the children’s bodies. Children were reminded to sit up straight. That they could not eat. To keep their eyes up and on the screen.

In this moment, I am concerned that the parents were not surprised. That teachers would decide serving up discipline was more important for them to do live than serving up something relevant and responsive to the actual children – was not surprising at all. It was just…school.

At some kitchen tables parents felt a weight lifted as they experienced something unexpected. They felt something like curiosity. Or relief. Or hope. In other kitchens parents remembered the fear of humiliation and doubled down on their own resolve to discipline their children better in order to protect them from the same but also – still habitually seeking teacher approval of their choices.

It seems to me that these different small windows into the teachers’ choices reveal quite different items leftover in the sieve after we sift other things away. And if we can examine what is left there, perhaps we will be able to ask better questions about whether it is the stuff we really want to keep.

What are the consequences of reinforcing parents’ expectations of what goes on in school?

What are the opportunities, unique to this moment, in challenging those assumptions?

What are the consequences of a steady diet of forced compliance and corporeal control? How are these consequences exacerbated when they are reinforced over wifi straight into the home?

What are the opportunities, unique to this moment, to heighten our awareness of whether what we’ve caught in that sieve is the stuff that should be there?

What are the best ways we can support one another this year to ask new questions?