Children, Complicated Times, and School

What rights do children have to think together about the world? Not our version of the world — but their own? What rights do children have to make sense of their world — and what are the implications — who benefits when there is little place for that in school?

Children are, of course, aware of what they see and hear and making sense of it all, all the time. It’s how they survive.

So what kind of sense results when their teacher lets them talk about the Oregon Trail but not the migrant caravan? When there are readings about Martin Luther King, Jr.’s dream but not what happened to an uncle last night who was pulled over by police? When there’s a quiz on the Civil War but no time to discuss the exclusion that happens on the playground? When a 5-paragraph essay must be written about the three branches of government but the government is shut down and your family is worried about the rent coming due? What sense do they make of the in betweens?

The world comes in every day. It is rich and complex and beautiful and mysterious and scary and we are alive in it, even during the hours we’re in school. Worlds collide in the classroom. This is a GOOD THING. This is what makes the classroom the most important place of civic engagement. Teachers can orchestrate this collision into a complicated symphony of perspective and experience and voice — if they are willing to navigate moments of cacophony along the way. And if they are willing to write the music alongside the children, so the notes are their own, because there is no song without them — no song until they write it.

There is cacophony in the Willow classroom (children ages 9-11) these days. Teachers are working to orchestrate a beautiful sound. Minds and hearts are deeply engaged in difficult, unanswerable questions. Trying to catch a rhythm in a world that doesn’t have one is a tricky thing to do. And it’s an urgent thing to do.

Oregon students study Oregon history at this age and so often this means a study of the Oregon Trail. The Willow class is no exception. They’ve read books from the perspective of the pioneers and visited the Oregon Trail Museum and imagined packing the wagon and churned some butter. They’ve interviewed their families about their own histories of coming to Oregon. They’ve studied the impact on the people who were here first. But what more can they do about that? It is an unimaginably tragic story. And the children who happen to make up this classroom know that in this story, they aren’t the good guys. They know in this story, the bad guys won. So, what do we typically do with this? Rather than dwelling in guilt and despair, we categorize this story alongside other sad – but over – stories and move on with our lives.

But what is this story, really? Isn’t it a story of migration and immigration? Isn’t it about power and violence and colonization? And racism and exclusion? And fear and dehumanization? We don’t have to look back 150 years to find that story. We just have to wake up in the morning. We say that history repeats itself but maybe we just think it does because in school those stories had endings. We are bewildered when they play over again. In school we were taught that the story happened then. Long ago. And it’s over now and it didn’t have anything to do with us, anyway. But it is our very alienation from these stories that keeps them on repeat.

So rather than moving on from the story in an alienated way, we started looking for connections. When we asked the children in Willow if they saw any between the story of the pioneers on the Oregon Trail and the migrant caravan currently walking towards the United States, their response was immediate and deeply engaged. The world floods into the classroom when you invite it. Children are so eager to explore it with each other. They know they need each other to understand.

When, several weeks later, we asked the children what they knew about the government shutdown, their stories were personal. An uncle. A cousin. A neighbor was out of work. We asked them if they knew why the government was shut down. Of course they did. They are in the world and this stuff is hard to miss. Neuroscientist, Immordino-Yang, tells us that we can only think deeply about the things we really care about. They really care about what is happening in their world.

Without attribution, we asked them to read this quote:

Why do people build walls, fences, and gates around their homes?

They don’t build walls because they hate the people on the outside but because they love the people on the inside.

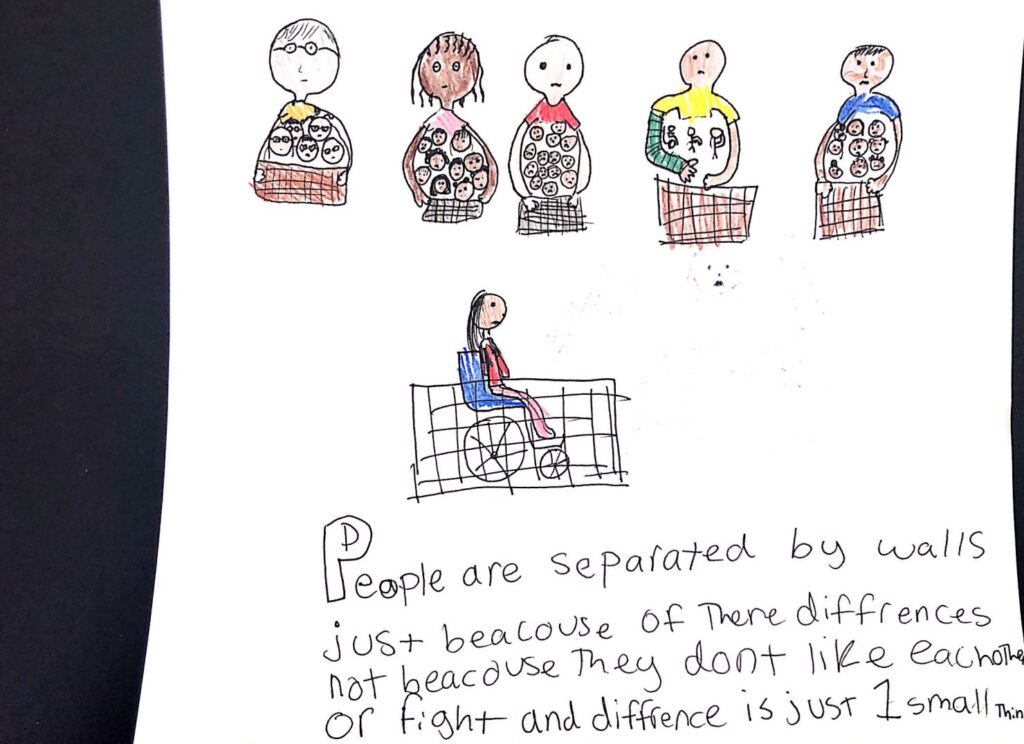

And then we asked them to draw, using black line pen and colored pencils, the image that came into their mind when they read that quote. We expected that the drawing tools would both challenge and support them to articulate this image with detail, and to have to slow down around its inherent tensions. When they finished, we asked them to walk around the room and take a look at all the different ways they represented this idea. Then we asked them to share the ideas they struggled with as they drew. Several children remarked that it was difficult to draw what was on the “other” side. They didn’t want to portray the other as “bad”, and it was a challenge not to. One child said that it was sometimes hard to tell which side was the inside. Another child said, “I didn’t even realize what I’d done until I looked at some of the other drawings. I had drawn bad guys on one side and good guys on the other.”

Do we think in good guys and bad guys because that’s the way we think? Or do we do that because that’s the story we believe?

Maybe the real problem is that we’ve never done the work of figuring out how to write a new story. The classroom can be a place where we start.

When we invited the children’s experiences with current, historical and personal events to collide, and asked them to draw, and then share — possibility cracked open. Awareness was raised. There was a story that some children were telling themselves that they didn’t even realize they were telling until confronted with another way of looking at things — literally, and through dialogue.

One child wrote:

I used to think that there was a good side and a bad side. Now I think that there is not a bad and good but just different perspectives. It’s just your perspective on other’s perspectives — and then some people categorize them as bad and good sides. I am still confused why the government is shut down. People in class say because they can’t agree but on what? Trump wants to build a wall. They can’t agree on what to spend their money on. What do the people who don’t want a wall want?

There is so much more work to do before we get a rhythm and find a melody. When we told the children that the quote was from Donald Trump, it was disorienting.

Another child wrote:

I used to think that Donald Trump was going to build a wall to just block everyone out (the immigrants) and that would make “America Great Again”. But now I think that he’s making the wall because he is afraid of the terrorists and stuff and he thinks he is protecting people when he is actually making them MAD.

And another:

I thought that quote was said by a young American citizen like 20’s or something. I thought it was really meaningful and took stress from bad and good off me. But when I found out it was Donald Trump’s quote I was pretty amazed because I have been influenced by the world around me to think that Trump is a bad guy and only cares about himself. I knew that if the Willow classroom had gone into this knowing Trump had said the quote they would be angry and kinda mad but it kind of tricked us up.

Our Democracy will benefit when our classrooms are places where we create opportunities for children and adults to move headlong into thought experiments together where they are deliberately “tricked up” for a time. In this place, where nobody is right or wrong, where diverse worlds can entangle with one another, maintain their own identity and also find community, where ambiguity sustains and transformation is what we seek — these are the places where we’ll learn to revise our story.

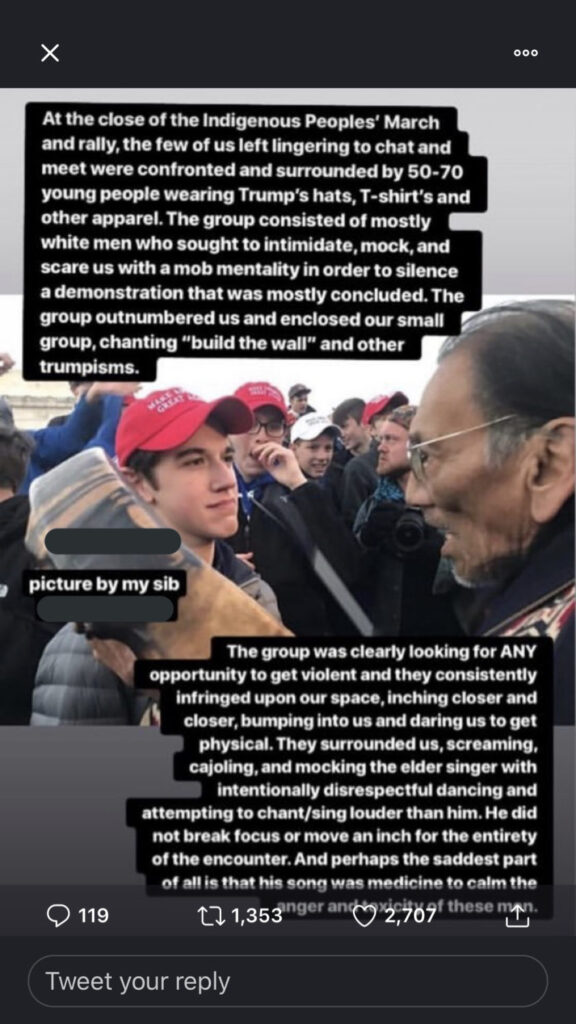

This morning on Twitter, the story captured in this photo is being shared on so many feeds.

I wonder: What is this group of overwhelmingly white boys afraid of? Where did they learn to act that way? Where might they have had the opportunity to learn something different? School is the most influential place I can think of – particularly the time in school when their brains were very young. I have a hunch that those boys went to schools where their playground emotions were a distraction to the classroom. I imagine their school valued individual test scores over opportunity to learn how to collaborate with others. I think it’s likely that they covered American history without an opportunity to participate in dialogue that helped them empathize with different perspectives, strengthen their own agency and capacity for making change. I bet there was no real place for imagination, creativity, curiosity, or play. No time to participate in the arts. These assumptions are safe because research is pretty clear that when all of these conditions are true, it leads to behavior like that. These boys don’t have to care about feelings anymore. They have power instead. And the capacity to think deeply has been lost to them. I’m sure that the teachers and administrators in their schools faced all kinds of pressures from parents with ideological viewpoints that would not support these efforts and accountability issues that prioritized test scores (achievement) over everything else. I’m sure it would have been so hard to push back on that — even if there was a recognition of what was at stake.

I know that so many of us did not get into this work with an expectation to that we would be on the front lines of a battle for the health of our democracy and the sustainability of our planet — even though we always were. And so now we must work together to create a collective vision of the work that lies ahead. We must be kind to one another. We must allow ourselves to try things that don’t work out. We must not pretend as though any of us has this all figured out. We need to listen. We need to read widely from widely diverse perspective. We need to ask questions. And we need to be okay with being afraid. Because that’s the only way that courage shows up.

Susan, what a wonderfully thought provoking blog! When children are discussing something meaningful to them, emotions run high, and yes you need the cacophony before the melody. Thank you for reminding me of this. As I go to school today thinking about MLK, I now have more courage to also include tiday’s World.

Such a powerful, thought provoking piece of writing Susan. Thank you so much for telling specific stories about Opal students and teachers and also the world that is unfolding right now. This is all such critical and important work for all of us who live and work in schools. Thank you for Opal. Thank you for your work every day, and thank you for your writing.