Children as Researchers of Their Own Learning

By Susan Harris MacKay

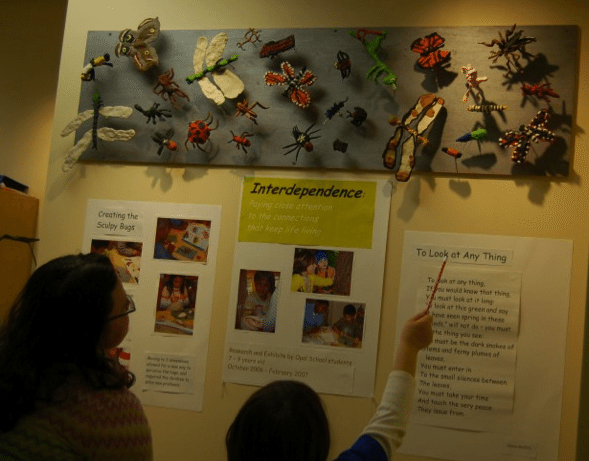

Not too many years ago, a group of 7 – 9 year olds, my

co-teachers and I created a bug museum. Using the Mantle of the Expert structure developed and described by Dorothy Heathcote, we created a fictitious

context for children to work within – in this case, an anonymous donor had

placed an ad in the paper looking for a group who would be willing to create a

museum that would support visitors' consideration of the important interdependent

relationships within our natural world. The children, of course, were thrilled

to apply. And, of course, they got the job! This context, and others like them,

invited a playful attitude, and engaged the imaginations of the children. But

it also gave them a real reason to begin researching what is known about the

insect world and ecological interdependencies.

I want to begin by sharing with you a poem written by two

seven-year-olds involved in this project:

On a silver

Bug-filled night I can

Hear the crickets chirping

And the mosquitoes jerk

From side to side

On a silver

Bug-filled night I can

See the hoppers hopping

High and low in the tall green grass.

I am listening to everything

They say.

By Maya and Anna

Human beings have a unique and profound capacity to

experience the rich complexities of life.

Children, in particular, overflow with this capacity—learning by making

meaning from experience– uncovering the layers of meaning that exist

everywhere around us, deepening our appreciation for complexity, and the need

for inquiry.

Four big questions guided the research of the adults through

this project:

- What does

it mean for children to be researchers of their own learning? - What kind

of environment supports children to be researchers of their own learning? - What tools

and natural learning strategies do children use as researchers? - What

inspires children to act as researchers?

But what do we mean by research? Here’s a snippet of

conversation the children had about that question:

Scouten: We took

what we knew and we took what they knew and we sort of, made a new pudding.

Julianna: We

gathered information from people who had researched more about it, and then we

took from our schema and mixed it together…

Scouten: And put

it into our own words.

Byron: And we

also put together some facts by just talking and a little bit of arguing.

I believe that when dialogue sounds like this in schools, we

are on the right track. Children interrogate each other’s ideas. They express themselves– listening, questioning, and

being transformed. They create shared meaning and understanding— and they understand that can happen

even in the midst of disagreement.

It is our unique capacity as human beings to create and

express novel ideas. With others,

we have the opportunity to make new connections and thoughts, and to bring

about change as we listen and negotiate with one another. This human capacity is how we find out

more about who we are—by having our ideas reflected back to us by those we are

with.

Loris Malaguzzi wrote:

…Dialogue is the child’s way

of inventing new directions, of enlarging the possibilities of speech, of

enriching one another. I believe

there is no possibility of existing without relationship. Relationship is a necessity of life.

That’s why this article is not really about how we created a

bug museum, though that is interesting, too. More than anything it is about the power of dialogue and the

relationships a community develops when it develops the habit of

listening. It is about the work we

did together using the context of the museum to create a classroom culture that

acknowledged human beings as natural inquirers, where all the participants had a

chance to discover what they had to offer, and therefore ended up knowing themselves

better—which should be the ultimate goal of education—for people to know who

they are.

Because this is not a story about how to do a bug project, I

have created a framework to share that I hope will have some relevance to you

in your contexts:

When you

present a text of interest, within a

culture of inquiry, for individual

and group interpretation and reflection,

you create a community filled with shared

meanings which support each member to discover the unique gifts he or she

has to offer.

We have gotten used to the idea, in school, and in our

larger culture, that what research and science have to offer lies somewhere

outside ourselves.

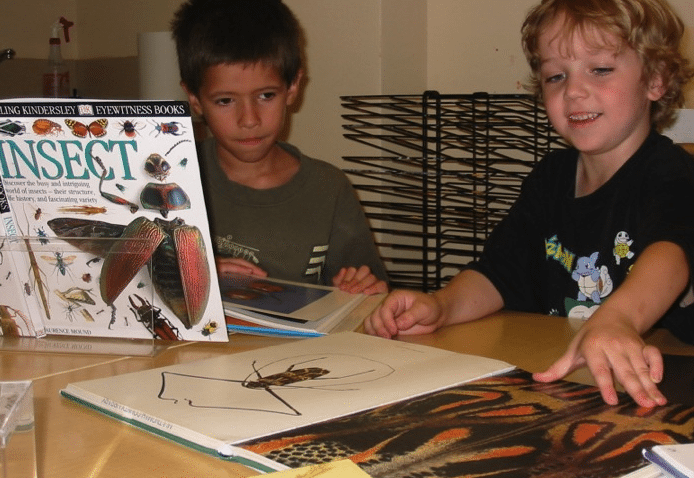

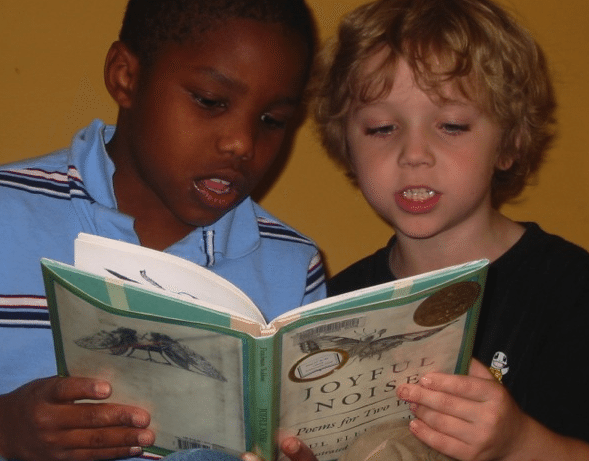

But learning is an inside-out process. Two boys may read the same book, but

the connections they make to their prior knowledge are unique. Their relationships to the material are their own.

So when

we ask the question, “What does it mean for children to be researchers of their

own learning?,” we are wondering how we can best support children to recognize,

express and reflect on their own relationships to curriculum or subject matter.

In his book The Informed Vision, David Hawkins

wrote:

The

constructions of science are not buildings, not machines, not instruments,

though these may be among its modes of expression – as may be the textbook… The

essential construction of science is a personal way of being related to the

universe.

However science may express itself, whatever the products

may be that our research inspires us to produce, what we are essentially

constructing as we research is our own relationship with the universe.

So how do we create a school environment in which children

have time, as a first priority, to develop their own understandings of

themselves—both as individuals, and as members of the community?

We have found that one element that must be present in the

environment is what we’re calling a “text

of interest”. At Opal School,

we have come to use the word text to mean anything that exists to make meaning

of.

The texts present in an environment provoke ideas,

questions, and emotional responses, including curiosity—a critical emotion to

engender and sustain.

Eleanor Duckworth writes: Curriculum development goes hand in hand with following the intricacies

of the development of ideas.

It was as we observed the development of ideas throughout

the classroom that we made decisions about where to go next. Excitement about

the provocations and books we read aloud that were related to bugs and insects

– which often amounted to conversations that were hard to stop, long

past the time that we expect most children are able – or willing – to sit still and concentrate–

convinced my co-teachers and me that we needed to develop curriculum that would support the

interests and move them forward.

Rather than simply following the children’s interest in bugs

and helping them keep bugs as a focus for exploration, we wanted to push them

towards bigger ideas that would have meaning across a wide variety of

contexts. This is where we have

the opportunity to match our stride to the children’s and not to fall behind

them.

In this case, we wished for them to develop an understanding

of the big idea of interdependence in the natural world, and the roles and

potentials of human beings in those relationships. We wanted them to extend their understanding of community to

include all living things, and to begin to realize the complexity of our

connectedness to the natural world.

A culture of inquiry,

which is part of the classroom environment, has at least two critical components

in terms of the way it feels: a

playful attitude and a sense of agency.

It needs to be fun—interesting, engaging, meaningful, and full of

possibility – and it needs to matter.

An environment conducive to research needs to be playful to

keep us relaxed and open to new ideas, and meaningful to support our need to

make sense of our lives.

We created the imaginative context of the donor and the

museum to bridge this potential gap between fun and serious work. Especially in dealing with such a

sophisticated, potentially abstract, and complex idea as interdependence, the

children’s brains needed to stay in a state conducive to creative thought.

This pretending game provided the element of play so vital

to human learning. Play reduces

the risk of failure and, in so doing, increases the children’s engagement and

motivation to participate. Play quite literally keeps our minds open to new

ideas by allowing connections to flow.

In the midst of real disagreement, community members who value listening

can make each other laugh.

Children don’t love to sit still—but they do love to share their

ideas.

The museum story context provided a sense of agency for the

children by providing the responsibility for the creation of the museum and

accountability to the donor who hired them.

In an essay on science education, David Hawkins writes that

the challenge to our education is “to

recover for our world the ways of learning that are concretely involving and

esthetically rewarding, that move from play toward apprenticeship in work”

Clearly, the creation of this museum required work that was

both playfully concrete and aesthetically rewarding. It was the sense of agency that allowed us to move towards

apprenticeship in our project. At each point, the children believed their work

was real—certainly, making the museum was real. So real research was a necessary part of that

apprenticeship.

A culture of inquiry values two kinds of research: finding

out what is already known, and wondering.

Both kinds of research were a constant throughout our

project.

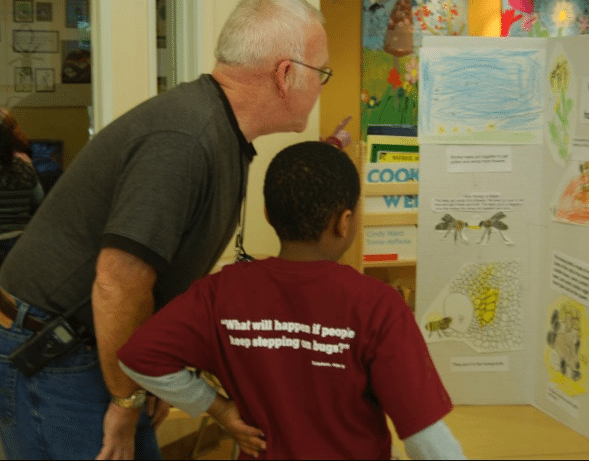

Following the intricacies of ideas as this project

progressed, the teachers decided to challenge the children to explore Tristan’s

big question—the one that had been printed on the new Opal School t-shirts:

What will happen if people keep stepping on bugs?

This question prompted research of both kinds. After sending

the children off for a week or so with the task of finding out what is known

about how a bug of choice travels, how prolific it is within it’s lifespan, and

how many human feet actually walk around in Oregon on any given day, we

gathered together for a discussion.

Rather than transcribe the

entire conversation, it is interesting to just relate the questions teachers asked as the discussion

evolved. As you read these

question, track what you notice.

- What are you noticing about the lifespan of various

insects and what are you noticing about the number of eggs they lay? - Tristan asked us a very provocative question. Does

that word, provocative, have meaning to you? - Do you have a prediction?

- A lot of you made the prediction that human

feet aren’t a threat of extinction. So, does that mean that it’s okay to be

stepping on bugs? - What other things are going on here? What other

things should we be thinking about? - What did you think about that when you said that?

- So what are you saying, Anna? What do you mean?

- I’m going to leave you with another question to

wonder about. What could be a serious threat to the life of your species? What

are some things that could make your species extinct? I’d love to hear your

ideas on that at another time.

What do

you notice about these questions?

As one of our most powerful texts of interest, we use the

children’s own ideas, questions, and products. In this case, Tristan’s question, asked during a discussion

much earlier in the school year, recorded in my journal, and brought back to

provoke the children’s thinking many weeks later, helped sustain the culture of

inquiry by supporting the children as agents of their own learning.

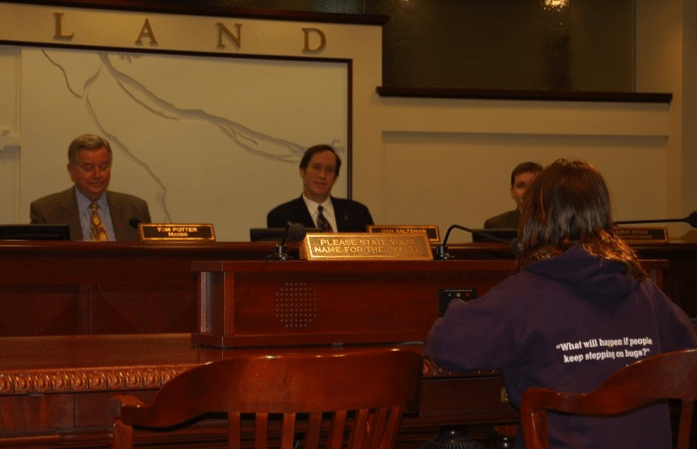

Through this imagined, playful context, the children became

real advocates for supporting their community to have a deeper appreciation for

the interdependencies around us. The tours they gave in their own museum gave

them the confidence they needed to bring their work directly to Portland's mayor and

city council.

In the fifth Opal School Online module, we’ll dig deeper into the role of the

arts in supporting a culture of inquiry.

It was an exciting morning, listening to Olive talk to Portland’s city council about the class’ research. Coming from tonight’s presidential debate, it’s clear that our world view can only be advanced by listening to children.

I think the article says it best. It needs to matter. Learning to be both playful and meaningful. If the children can’t make any connections and it doesn’t matter to them, they will not be engaged. We have seen this in classes at our Museum. When we follow the children’s thoughts, ideas, and questions, they are much more engaged and in charge of their playing and learning. Allowing children to explore the world around them and investigate a question, develops such a rich and meaningful project both for the children and the teachers. Children are great communicators and researchers, if we just encourage them to do so. It is also really cool to see how children take pride in their work and research. In your bug project, the children were excited to share what they learned with each other, and to inform people, who weren’t involved, about it.

Reading through this article helps me to take back an idea,philosophy about results and the way, and things that happened…What I want to say is that not the final result is important, the most important thing is the PATH ,that each of us is going trough.